On how many days and in how many hours can you visit the 60th Venice Biennale, which opened with more than 80 country pavilions and around 120 collateral events? If you want to see the important museums in Venice embellished with contemporary artworks, what kind of performance awaits you? You have to choose, by looking at various art guides, which exhibitions you’d prefer to see. And in making this choice, it would be beneficial for you to have updated knowledge about contemporary art.

And once you’ve made this choice, the following problem still crops up: a queue of one to one and a half hours awaits you, particularly for the glorious pavilions of the UK, France, and Germany in Giardini. Entering the pavilions of the so-called non-glorious countries is much easier. In this biennale, the Russian and Israeli pavilions did not present difficulty, as they were closed due to their respective wars. However, one of the so-called non-glorious pavilions, Egypt, was an exception this year; an hour or two after the opening, word spread that Wael Shawky’s Drama 1882 was very interesting, and a long queue formed in front of the pavilion.

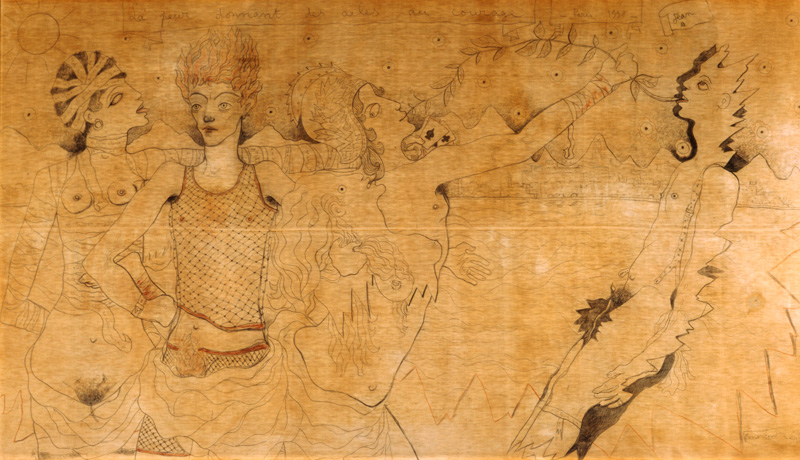

Courtesy the artist, Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Lisson Gallery, Lia Rumma, Barakat Contemporary

The most important feature of the Venice Biennale is that it unites in a mass context artists, experts, gallerists, collectors, sponsors, and those who use art as an exceptional visibility opportunity, especially on the opening days. The purpose of such a mass unification is to create a demonstration of an epistemological—as well as an undoubtedly economic—power of contemporary art production. These powers take on a special value when Europe and the Middle East are amid the various predicaments they’ve endured for almost a decade.

Crowds and Power

As one of the participants in this intense crowd gathered in Venice at the opening in 2024, amid ongoing political conflicts and regional wars, I suddenly thought about Elias Canetti’s Crowds and Power. Canetti’s 1960 book provides insights urgently needed in an age dominated by mass gatherings. At this Biennale, there were three distinct crowds: artists, curators, gallerists, collectors, and visitors; local organizers, invigilators, and security personnel; and protesters. All were in a state of uneasiness and expectation—or in some cases, indifference. This uneasiness stemmed from the political conflicts, wars, and economic, and ecological problems they left outside the Biennale, coupled with an expectation that the art they encountered would provide the comfort and hope needed to overcome these difficulties.

Under the title “Foreigners Everywhere”, which highlights the global inequality and persistent socio-political allegations against foreigners (or others) and reflects the current discourse on inequality, the Biennale raises questions about the common character of this crowd. Canetti’s wise thoughts provide an answer to this dilemma: “Within the crowd, there is equality. This is absolute and indisputable and never questioned by the crowd itself. It is of fundamental importance and one might even define a crowd as a state of absolute equality. As soon as a man has surrendered himself to the crowd, he ceases to fear its touch. Ideally, all are equal there; no distinctions count. Not even that of sex. The man pressed against him is the same as himself. He feels him as he feels himself. Suddenly it is as though everything were happening in one and the same body.” (1)

With Modernist, Post-modernist, and Relational Aesthetics artworks created by women, men, and LGBT artists—dead or alive—from five continents, this equality is displayed as an absolute truth in contrast to the perceived equality of the crowd. Viewed from this perspective, the “foreigners” in the title of the biennale prompts people to reconsider the concept’s validity ( or to question the invalidity of this concept).

The meaning of this equality becomes clear when you watch the opening day videos on YouTube, showing the crowd wandering with almost the same attitude. It seems that in this biennale, Pedrosa and his team invite this privileged mass, which is the main interlocutor, to examine the immigrant and refugee issues from the perspective of the works they see. The artworks and the artists who create them highlight the symbolic richness of traditional and contemporary art from the countries colonized by the EU masses, who see them as foreigners. Especially The Museum of the Colony, located in the main pavilion in Giardini, is an exhibition where this message’s history can be explored in depth. The Arsenale exhibitions, starting with the uncanny hybrid figure carrying indispensable necessities on his back by British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare, further this message. Shonibare established a foundation (YSF) in 2019 to explore colonialism and post-colonialism within the context of globalization. The whole exhibition in the Arsenale is structured on the same message: The creations and inventions of civilization and the creative power in the productions of people from the other four continents throughout the 20th century and today, whom you do not acknowledge, indicate that you must reconsider this irrational rejection.

Classifying exhibitions in biennials is not a difficult task. Generally, the participating artists produce works on political, economic, cultural, and ecological problems related to their countries or global issues. Undoubtedly, they can do this to the extent that their countries’ democratic processes allow. It is sometimes surprising when serious criticism is seen in the work of an artist from a country with limited freedom of expression, and the artist immediately receives attention and respect.

Less-known geographies and lesser-known artists

Since postmodernism and globalization have somewhat diminished the dominant privilege of the EU and USA art scenes, seeing works of art produced in remote and less-known geographies and by new and lesser-known artists in biennales has become common. These works often include examples of historical, local, indigenous, and traditional arts and handicrafts, equipped with the tools and techniques of today’s visual art. A decorative line has become firmly established in contemporary works of art, which is gloriously observed in this biennale, critically named as foreign. Yet, they cannot escape the fact of pleasing the desires of the society of spectacle.

Many countries with damaged democratic processes in today’s geopolitical conditions participate in the Venice Biennale. I will not list them here as the list of these countries is too long in the global context. Approximately 40 countries are governed by authoritarian regimes, yet most of these countries open pavilions at the Biennale, even though the constitution of the Biennale is supposed to allow completely free expression. We can observe how the artists from these countries cope with this inconvenience through the covering strategies they apply in their work. However, it’s important to remember that this issue is not exclusive to authoritarian countries; even democratic countries face such challenges. This year, an EU country, Poland, also had a censorship issue. The commissioned work of Ignacy Czwartos, Polish Practice in Tragedy: Between Germany and Russia, which was set to include over 35 works envisioning Poland as oppressed by Germany and Russia throughout the 20th century, was censored by the Polish government. (2)

Gregor Schneider won the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale for the German Pavilion in 2001. In 2005, he became the subject of a scandal when he intended to show CUBE, a 50-foot-tall sculpture draped in black fabric meant to resemble the Kaaba, in a group show. The Biennale’s organizers, including Rosa Martínez, rejected the work for “political reasons,” fearing it would incite anti-Islamic violence. (3)

In the 2009 Venice Biennale, Emily Jacir was commissioned by Palestine to create a cross-cultural exchange work called Stazione. This project translated the names of each vaporetto stop along the Grand Canal into Arabic and planned to place the translations next to the names in Italian. It was abruptly canceled by Venetian municipal authorities without explanation. (4)

Christoph Büchel faced a similar fate in 2015 with his work The Mosque, a piece made for the Icelandic Pavilion that transformed a former Catholic church into a functioning mosque. (5)

Terry Eagleton offered a wise explanation for these paradoxes in his 25 April London Review essay: “Not all culture is ideological at any given time, but any part of it, however abstract or high-minded, can serve this function in specific circumstances. At the same time, however, culture can muster vigorous resistance to the dominant powers. This resistance is more likely to occur, curiously enough, once art becomes just another commodity in the marketplace and the artist just another petty commodity producer.” (6)

Turkey’s presence was once again quite visible in this Biennale. The pavilion journey, which started in 1991 in a 10m² room at the back of the main pavilion, is now in a central location in the Arsenale after various stages over 33 years. In 2015, in his exhibition curated by Defne Ayas, Sarkis presented a greatly moderated metaphor of the Armenian trauma of 1915; however, a slight crisis was overcome due to the phrase “Armenian genocide” in the catalogue, and the catalogue was put aside. Sarkis placed the collected catalogues in a chest and exhibited them in the area. Cevdet Erek made a very successful presentation at the 57th Venice Biennale with an installation titled ÇIN, both in terms of conceptual-discursive content and evaluation of the space.

İnci Eviner’s pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale was reminiscent of Erek’s installation in its form. It was an installation that conflicted with the naive patterns and concepts of her videos. Füsun Onur’s installation at the 59th Venice Biennale had an elegiac look, as she could not physically oversee the work due to personal difficulties, resulting in an unconvincing presentation. The organizers should have showcased her retrospective work, reflecting the feminist movement in Turkey since the 1980s. At the 60th Biennale, Gülsün Karamustafa created an installation referencing Turkey’s state of affairs: politics was highlighted with a video of mass protests, Murano chandeliers represented the three religions, steel containers filled with colorful glass shards pointed to the construction industry glorified by capitalism, and plastic column casts depicted the touristic ancient cultures of Anatolia. Pillars became a debatable item; whether consisting of plastic ancient column molds imported from China, are suitable for this installation, which actually has a compact conceptual structure.

In my view, it would be more beneficial to hold group exhibitions with experienced curators in this architecturally dominant venue in the future. The Venice Biennale Pavilion of Turkey should serve younger generation artists who lack opportunities to appear on international stages due to economic and political constraints. More comprehensive retrospective exhibitions should be organized for senior artists who were not appreciated during their prime. In the elusive context of socio-geographies like Turkey, their work from four to five decades ago is often more significant than what they produce now.

Protests organized by NGOs

The first day was marked by significant protests organized by several NGOs in front of the USA pavilion and the adjacent Israel pavilion. The USA pavilion featured indigenous-traditional art forms from the American continent. Jeffrey Gibson (born 1972), a member of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and Cherokee descent, decorated the pavilion with vibrant colorful patterns and filled the rooms with exquisitely beaded figures, satisfying the desires of the society of spectacle. The protests were expected, as the Middle East crises, which have caused wars for a while, were brought to the forefront in biennales, and those responsible for these crises were protested. The conflicts between art, politics, and the economy are persistent issues that need ongoing discussion. Globally, artists are aware of these contradictions and address them in their work, often delivering important warnings. Many works in this biennale contain such warnings, messages, and reflections.

In the official list of National Pavilions, there is no Palestinian Pavilion because Palestine is not recognized as a nation by the Italian government. However, there were several independent Palestinian artists present in this biennale, as in previous ones. For example, in the 53rd Biennale in 2009, when global politics were less intense, a remarkable exhibition was curated by Salwa Mikdadi and commissioned by Vittorio Urbani at Convento Ss. Cosma & Damiano, Campo S. Cosmo, Giudecca Palanca. This exhibition featured artists such as Taysir Batniji, Shadi HabibAllah, Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti, Jawad Al Malhi, Emily Jacir, and Khalil Rabah. Notably, in 2007, Emily Jacir became the only Palestinian artist to be awarded the Golden Lion. The absence of an official Palestinian Pavilion this year is not surprising, but still, a manifesto was distributed, entitled The Palestinian Pavilion – What is the Future of Art – A Manifesto Against the State of the World. (7)

Among the diverse contributions to the biennale, the Vatican’s groundbreaking project presented a socio-cultural responsibility concept. Eight artists contributed works located inside Venice’s Giudecca Women’s Detention Home, with Maurizio Cattelan’s work displayed on the building’s façade. Workshops were also created with the active participation of inmates and artists. Pope Francis himself visited the Holy See pavilion, curated by Chiara Parisi and Bruno Racine, entitled “With My Eyes,” on April 28, marking the first time a pontiff has visited the Biennale. During his visit, the Pope spoke with the inmates and said: “Paradoxically, a stay in prison can mark the beginning of something new, through the rediscovery of the unsuspected beauty in us and in others, as symbolized by the artistic event you are hosting and the project to which you actively contribute.” (8)

The Pavilion of Germany attracted immense attention as always, particularly due to the ongoing Israel-Hamas war. Curated by Çağla İlk, the exhibition featured works by Yael Bartana, Ersan Mondtag, Michael Akstaller, Nicole L’Huillier, Robert Lippok, and Jan St. Werner, and was extended to the island of La Certosa with the timely theme: Thresholds. Israeli-born Yael Bartana, who represented Poland in 2011 with her exhibition titled …and Europe will be Stunned. This time, she has presented a utopian proposal against global destructive realities with the concepts of “search for a way out” and “possibilities of future survival” in a darkly humorous piece titled Light to the Nations – Generation Ship.

Ersan Mondtag blocked the pavilion entrance with a huge pile of soil, which can symbolize the truth about nature, -if viewed optimistically,- and negativity, limitation, and historical memory accumulation – if viewed critically. Notably, the German Pavilion has consistently featured architectural interventions since Hans Haacke. Inside, Mondtag constructed a phantom-like tower house filled with metaphors of both private and common uncanny settings.

Since Zineb Sedira’s 59th Venice Biennale presentation in the French Pavilion, which featured a complete reconstitution of her home in Brixton, South London, titled Dreams Have No Titles (9), the themes of “home” and “room” have become popular among artists. The Bulgarian Pavilion exemplified this trend with its installation titled Neighbours, conceived by Krasimira Butseva, Lilia Topouzova, and Julian Chehirian. This installation is the result of 20 years of historical and artistic research into the silenced and faded memories of survivors of political violence during the Communist era in Bulgaria.

The metaphor of room (home) installations has a profound history, beginning with Kurt Schwitters in 1923. Schwitters created a claustrophobic and cubist installation titled Merzbau in his house in Hannover, which was destroyed during the war in 1943. The title Cathedral of Erotic Misery served as a preliminary concept for today’s room and house installations. As a tribute to Merzbau, Gregor Schneider brought most of the rooms from his Haus ur to the German Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2001, making his previously private work accessible to the public. In the 1970s, Marcel Broodthaers produced several rooms titled Décor, A Conquest, which have been re-installed in various exhibitions. In 1956, Richard Hamilton created a series of collage paintings on the rooms of consumer society, the most famous being Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?. In 1962, he exhibited a room installation titled The Store in Green Gallery. The exploration of home metaphors in art continues to this day.

Exhibitions at the museums

The exhibitions in Venice’s two iconic museums always attract as much attention as the Biennale itself. Julie Mehretu’s exhibition at Palazzo Grassi showcases her work from the past twenty-five years, featuring more than sixty paintings and prints, including recent pieces from 2021-2023. Mehretu, a leading Ethiopian-American abstract painter and printmaker, reflects the modern urban experience with elements of city plans, architectural drawings, and maps. The exhibition also includes works by her fellow artist-friends Nairy Baghramian, Huma Bhabha, Tacita Dean, David Hammons, Robin Coste Lewis, Paul Pfeiffer, and Jessica Rankin.

At the Peggy Guggenheim Museum, there is an archival exhibition on Jean Cocteau (1889–1963), titled Jean Cocteau: The Juggler’s Revenge. The exhibition features drawings, graphics, jewelry, tapestries, historical documents, books, magazines, photographs, documentaries, and films directed by Cocteau, collected from various museums. The pieces narrate the tumultuous life of the enfant terrible of the French art scene and a major figure of Dada and Surrealism.

This Biennale, like several previous, aims to challenge the separation between “foreigners” and “US” that began with Modernism in art. In a time when racism, nationalism, and religious divisions are rampant, accompanied by war and extreme events, the masses cannot ignore the realities reflected by global artists: human creativity and labor are our most valuable hopes for the future.

Remembering Vilém Flusser at this moment:

Images must be explained or told, because as with every mediation between man and the world, they are subject to an internal dialectic. They represent the world to man but simultaneously interpose themselves between man and the world (“vorstellen”). As far as they represent the world they are like maps; instruments for orientation in the world. As far as they interpose themselves between man and the world, they are like screens, like coverings of the world.

*VILÉM FLUSSER, POST HİSTORY

- Crowds and Power, Penguin Books, 1992, çev.: Carol StewartMasse und Macht, Claassen Verlag, 1992 © Claassen Verlag (s.15 )

- https://www.artandobject.com/news/artist-rejected-venice-biennale-polish-pavilion-says-he-was-censored

- https://www.artnews.com/feature/venice-biennale-controversies-christoph-buchel-gran-fury-robert-rauschenberg-1202697214/

- https://www.artnews.com/feature/venice-biennale-controversies-christoph-buchel-gran-fury-robert-rauschenberg-1202697214/

- https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v46/n08/terry-eagleton/where-does-culture-come-from

- https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/venice-biennale-2024-israel-pavilion-palestine-museum-us-proposal-rejected-1234684101/

- https://hyperallergic.com/903608/activists-say-no-to-the-genocide-pavilion-in-biennale-protest-against-israel/

- https://apnews.com/article/pope-francis-venice-biennale-885ddbcd4171c3ba08e1e8ee6039ddc2

- https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/19/arts/desig n/venice-biennale-zineb-sedira-france.html

- Vilém Flusser PostHistory, translated by Rodrigo Maltez Novaes U of Minnesota Press, 2015