Businessman, collector, and founder of ARUCAD University, Erbil Arkın is one of the key figures who has transformed the cultural landscape of Northern Cyprus through his investments in the business world and his support for art and education. Bringing his experience in sectors such as banking and tourism to the field of art, Arkın has built a world-renowned sculpture collection over the years, particularly due to his deep interest in Auguste Rodin. We spoke with Erbil Arkın about his journey as a collector, the story behind the founding of ARUCAD, his passion for art, and his dream of building cultural memory in Cyprus through art.

Let’s start with your story of going to England…

I was the youngest in the family. My father emigrated to England after leaving the army. He saved up for the ticket and other expenses, then sent the tickets to my mother. At that time, airplanes were only for the wealthy; besides, flying to England took 12-14 hours.

So, were there stopover trips?

Yes, you had to take connecting flights. But what I really want to say is this: I always boast about my mother. She was an uneducated woman; she couldn’t read or write. She only knew a little old Turkish. Why? Because her mother had passed away when she was 12 years old. My grandfather took her out of school, saying, “You’re going to be a mother now.” But that “uneducated” woman took her three children and set sail from Genoa. From there, she took the train to France, and from France, she took the train again to England… She reunited us with my father. Thank God, we were together. I grew up there.

Where did you live in London?

We started our life in the poor areas of London. Our first home was in East London, in Newington Green. It was a basement apartment. I saw my father for the first time there, and I still remember how scared I was of him. In our kitchen, there was a bathroom right in the middle; it had a lid on it. That lid was our dining table. On bath day, the lid would be opened, and it would turn into a bathroom. That’s how we started our life. My mother sent me to nursery because she had to work. She was a seamstress. My father also worked in various jobs. Everyone tells me to “tell them,” so I’m telling them like a book.

I’m very curious…

At kindergarten, they noticed I had a talent for drawing. They took me out of the class for 5-year-olds and put me in the class for 7-8-year-olds. That was a source of pride for me. As I felt proud, my goals evolved. Drawing was a passion for me. I told everyone, “When I grow up, I’ll work at Disney and draw Mickey Mouse.” But as I grew up, my goals changed. When I started high school, we had an extraordinary English teacher who loved art. He made us love art.

So your passion for drawing guided you?

Yes. I became interested in plastic arts and sculpture. That became my dream. Thankfully, I was able to go to university, but my family was very poor. I studied with state scholarships. They even gave me a scholarship in high school. The state paid for my bus and train tickets. I went to university on a scholarship. I made ends meet by flipping burgers on weekends. It was all life experience. But at some point, I realized I would either become a teacher or a very poor sculptor. I was overwhelmed by poverty. I changed my mind halfway through. I turned to industrial design. I studied furniture design, architecture, and interior design. This table, for example, is my work. It was made in our shipyard. Olive tree wood was used. They were going to be burned, but we saved them.

“Was I Born Here?”

So what place did Cyprus hold in your life at that time?

My mother gave me a trip to Cyprus as a gift when I was 18. Of course, there were planes back then. When I first arrived on the island, I heard cicadas, saw palm trees for the first time, and felt the heat. I had come from the concrete of London. I was struck. I fell in love. I said, “Was I born here?” I came back in 1973. The same passion. These mountains, this land… I said, “One day I will live here.” And we came. We took a chance.

How did your life change after returning to Cyprus?

I felt something was missing in this country. At first, everyone was chasing pools, villas, and Mercedes, but we lacked culture. I said, “We are culturally very poor here.” About ten years ago, I made a decision: I had to open a school. But at first, my goal wasn’t a university, it was an art school. One based on manual labor, like in England. A place where people get their hands dirty with art, where they become masters of their craft. A “craftsman” school…

But then it turned into a university, didn’t it?

Yes, because after conducting research, they told me, “In Cypriot and Turkish culture, families don’t send their children to such a school. They see it as ‘apprentice work.’” So I changed my mind. I decided to make it a university. We set out unconsciously but with great intention. My goal was to establish a “university of creative arts and design.” Our field would be narrow, but it would encompass a wide range of subjects. I wanted students who would get their hands dirty in the workshop, not those who would draw on a computer. I wanted to train individuals who would have real professions. I didn’t want them to be like me.

What happened when you graduated?

In our class, 27 people graduated, but only 6-7 were able to pursue their profession. The rest became teachers. I didn’t want that kind of ending. So when we founded ARUCAD, our philosophy was this: workshop-based education, getting your hands dirty, becoming a master. Students would reap the rewards of their labor in the form of a profession.

When I visited the university, I was really surprised. There were practical applications in the ceramics workshop, in glass, in every department. This is something we don’t see much in Turkey.

Actually, I wanted students to take the courses they wanted for the first two years, then choose their fields. At our university, someone studying interior architecture can take ceramics or glass courses if they want. Like in America… But the system isn’t like that in Turkey and Cyprus. Once you enter a department, you have to finish it. But can an 18-year-old really know what they want to do?

What is your long-term goal for this university?

I don’t go to the university much anymore. But I keep a close eye on everything. My goal is for this university to continue after me, my son, and my grandchildren, together with the foundation I established. In other words, it should still be standing four or five generations from now. It should be an integral part of Cyprus’s character. It should still be here a hundred years from now. Even if the Greeks occupy this place, this university should remain standing. It should be part of Cyprus’s culture and identity.

You are talking about Cyprus’ unique culture. What kind of structure do you think this culture has?

I am also a child of that culture. British culture has already permeated us. We are Turkish, after all. We have also experienced Greek culture. It is a harmony. Perhaps we are not as religious as the Greeks, but we Cypriots are a mixture. The Greeks may have taken the architecture, but not the culture. The British influenced everyone. Even our accents became similar. The accent of Turkish Cypriots is very famous, like “napan, mapan”… Greeks use the same accent because they grew up in the same environment. Our accents are the same, but our religion, language, and way of life are different.

The Issue of Identity

So did you learn Turkish later in life?

Yes. When I came to Cyprus, I didn’t know any Turkish. I never read Turkish either. I learned everything by listening. My mother tongue is English. But I learned Turkish over time. Now I can speak three languages, but I still feel something is missing inside me.

What is that sense of incompleteness?

The issue of identity. When I go to Turkey, they call me “Cypriot”; when I go to England, they call me “Turkish or Cypriot”; and when I return to Cyprus, they call me “English.” I don’t feel fully belonging anywhere. This has become my fate. But if you ask me, I am Cypriot.

This is also a great richness…

Yes, it’s a spiritual richness. It’s evident in my accent; it’s a complete mix: English, Turkish, Cypriot…

You continue your relationship with art.

My love for art never ended. It was always inside me, even when I was working. When I was married, I rented a separate apartment and set up my own studio in 1991-92. I painted in oils. But the workload was heavy, and I had to give it up again. My passion for Rodin, however, has always continued.

How did you come to know Rodin?

When I was 16, our English teacher took us to the Tate Gallery. There I saw Rodin’s sculpture The Kiss. I couldn’t believe that a work made of marble could be so emotional. In an era without the internet or telephones, I asked my teacher, went to libraries, and researched. I discovered Rodin’s other works, then I was introduced to the Impressionists. That’s how the passion began.

How did the path to collecting open up after Rodin?

It was probably about 18–20 years ago. My business was going well. While heading to my bank in England, I passed by a gallery window on Pall Mall. I saw a sculpture inside and really liked it. I had never purchased a piece of art from a gallery before, let alone a commercial one. I hesitated. But then I turned around and went inside. I met the gallery owner; we’re still friends. He showed me a sculpture that had just arrived, still fresh off the boat. It was Rivalta’s sculpture titled Restless. It was 12,000 pounds. I checked my wallet; I could afford it. I bought it. I was so excited that there wasn’t even room to put it in my mother’s house.

“I Have 31 Rodins”

Was that the first piece you bought?

Yes. But as I was leaving, I saw a small sculpture. I immediately asked, “Isn’t that a Rodin?” “Yes, it’s for sale,” he said. I was surprised. I said I recognized it. Then he said to me, “There’s an auction at Sotheby’s tomorrow, come if you want.” I went the next day. It was a whole new world. Everyone had catalogs, keyboards… Rodin’s sculpture Head of Lust came up for auction. “Shall we raise our hands?” he asked. “Raise it,” I said. And it went to me. Now I was the owner of a Rodin.

How many Rodins do you have in your collection now?

I currently have 31 Rodins. And my collection is still growing. I’ve started buying works by other sculptors as well. Rodin’s friends, masters, students… Works by Dalou, Boucher, Carrier-Belleuse… Now my house is like an antique shop. There’s a sculpture in every corner.

When did you first open this collection to the public?

I kept my collection secret for a long time. But ARUCAD University needed some buzz. I decided to declare my collection. We opened ARUCAD with my Rodin collection. It was the right decision because it attracted a lot of interest. Then the idea for the Rodin Gallery was born. We built this building. We opened a special place for the Rodins. Now there are 31 sculptures there. With our new building, the gallery will triple in size.

At first, they called me a “trophy collector.” My Rodin collection is now one of the most respected collections in the world. We will also add names such as Dalou and Boucher. They will all be exhibited together in the new gallery. I will also add the names of those who worked with Rodin and were influenced by him.

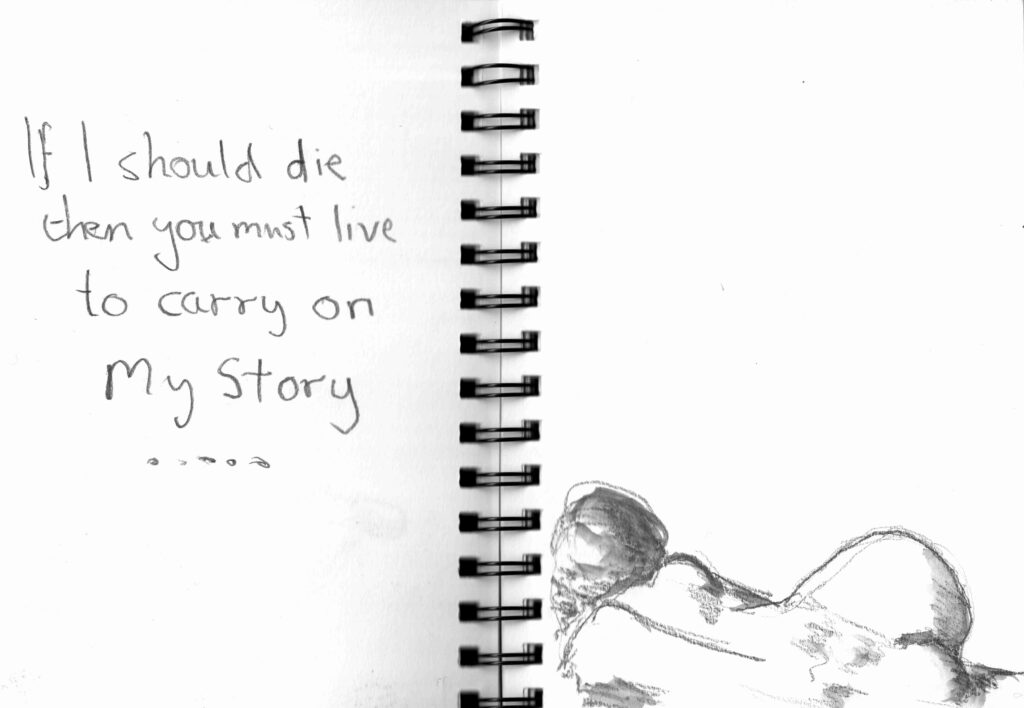

You are still producing work yourself, aren’t you?

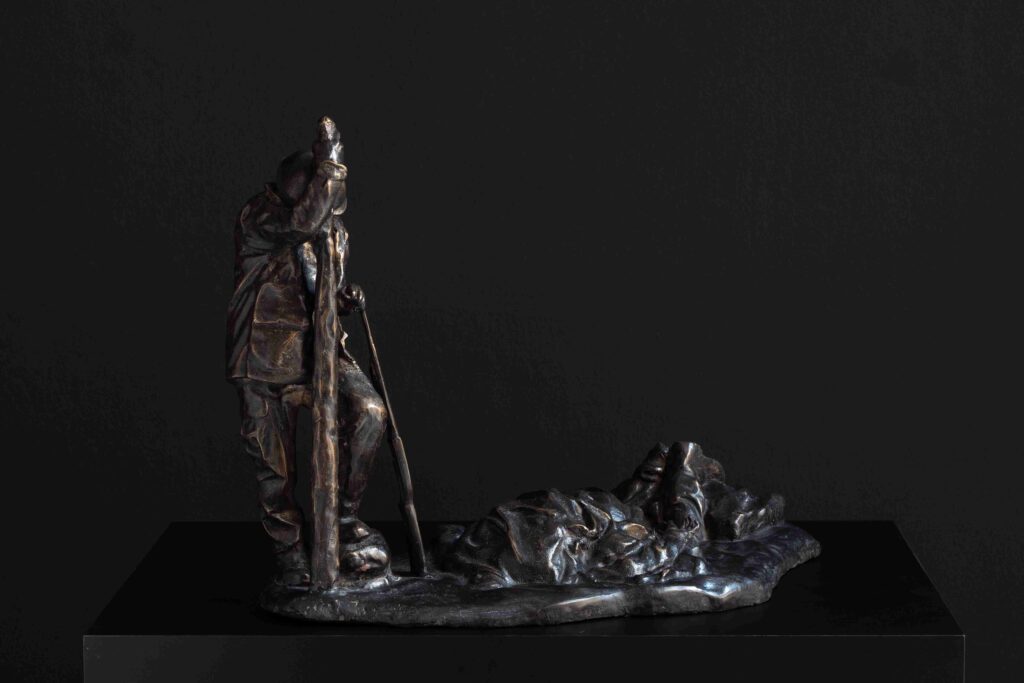

Yes. In fact, my work is featured in the book Anatomy of Anguish. Necmi Sönmez wrote it. I did my master’s degree at Aruca: those were the works that emerged there. I did oil paintings, I did sculptures. For example, there is a sculpture of mine called The Splendor of War standing behind you.

It’s a very striking sculpture. Is war really “magnificent”?

No, quite the opposite. The sculpture depicts a soldier lying face down, his head buried in mud, his buttocks exposed. There is nothing magnificent about war. It is only death and humiliation. The soldier left his village and died. It is currently being cast in bronze. I made it to show to students. I wanted to show that any material can be used: plastic, perspex… There are no limits to the imagination.

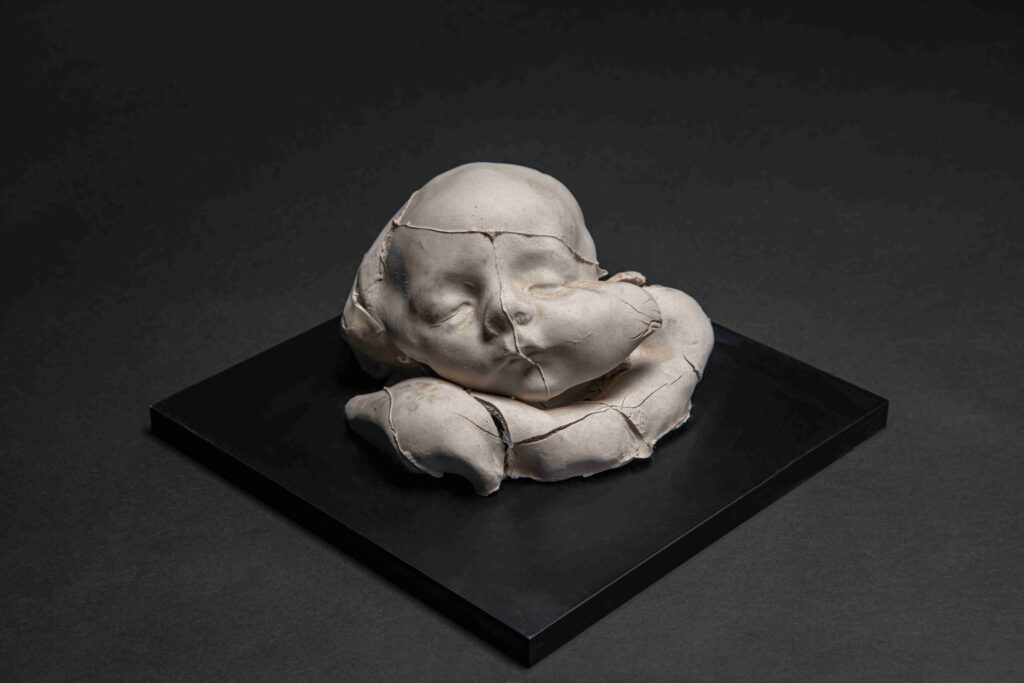

Have you ever had any faulty molds when producing sculptures?

Yes. Once, the figure that came out of the mold was distorted, the form had shrunk. But it gave me an idea. It was like a stillborn baby. I named it Abortion. It’s now in my office. These are meaningful works.

What material do you enjoy working with the most?

Definitely clay. I love working with mud. It’s the material I connect with best through the language of sculpture.

Are there any artists besides Rodin who have deeply influenced you?

Of course. Bellini, Michelangelo, Van Gogh, Renoir… But there is one I am passionately attached to: Egon Schiele. I love his lines, his narrative. If I had the money, I would definitely buy a Schiele. Maybe one day I will get one of his drawings. Sargent is also a great talent. He was far ahead of his time. But Schiele is a different kind of love for me.

There are many works of art in your hotel, the Iskele Art Hotel, aren’t there? Is it turning into an art hotel?

Yes, it is now known as the Art Hotel. But it will be filled with even more art. There will be art in every corner of the hotel. The paintings in the rooms, the works you see at the reception and in the restaurant are all for sale. There will be a label next to them with the price written on it. If you like it, you pay for it and take it with you. All of them are for sale. A new one will be placed in its place immediately. Nothing is unsellable.

“No Homeland, No Nation, No Sakarya”

Could you tell us a little about the Asil Köylü statue?

I’m working hard on it. I’ll do it one day. It has a heavy political dimension. That’s why the process is complicated. But that statue will exalt the people of this land. Whether they are Greek, Turkish, or Maronite, it doesn’t matter. Those people are part of this land. There is no homeland, no nation, no Sakarya in this project. There is no race, no religion, no language. There is only the land. The Noble Peasant will be a work that separates Cyprus from the issue of identity and connects its people to the land. This island has always been a place that people have wanted to share. But in the end, all we have left is the land.

The migrations in Cyprus have had a direct impact on your life. Your mother migrated to England, but what about your family?

We are a family of migrants. From Larnaca… We were exiled in 1960. The name of our village is Aya Anna, but we call it Aynanna. It was a beautiful place. Greeks and Turks lived side by side in that village. Everyone knew each other’s language. My grandfather even had two wives: one Turkish, one Greek. But the surrounding Greek villages attacked us. We became migrants in 1960. But this was not just our fate, it was the fate of the entire island. At least 60-70% of the population on this island has experienced migration at least once.

There were other forces behind these migrations, not just between Turks and Greeks.

In 1960, the main factor was the British. Cyprus was part of England at the time. The Ottomans had leased the island to the British for 99 years. After the war, Turkey was on the losing side, so ownership of Cyprus passed to England. At the end of the 1950s, the Greeks began their struggle for independence. The British said, “Go ahead, do whatever you want.” Turkey did not have the power to stop them. The Greeks saw Cyprus as a Greek island. They still see it that way today.

Didn’t the same thing happen in Crete?

Of course, Crete was no different from Cyprus. There, too, the Turkish and Greek populations lived together. But there, the Greeks were successful and exiled the Turks. The difference was that the Turkish Cypriots said, “No, this will not happen.” They resisted. The descendants of the Turks who were expelled from Crete still live in the Aegean. They say, “I am Cretan.”

Do you think a balanced price was paid between the Greeks and Turks?

I think some balance was achieved after 1974. Before that, everything was against the Turks. I started an initiative about this. Five years ago, we formed a lobby group. Lawyers, academics, myself… Our goal was to buy the Greeks’ property and compensate them. We changed the rules. For example, the land where this hotel is located: Even though the title deed is in my name, I paid the Greek owner. Now this property is mine under international law as well. The whole issue is this: We must compensate the Greeks in a humane and reasonable manner.

This is a policy that could bring about a significant transformation.

Absolutely. Because right now, no one in the world says, “I recognize the title deeds of the TRNC.” But if it goes through the immovable property commission, if it is taken from the Greek Cypriots, that property is recognized internationally. If we increase the property ratio from 16% to 26%, to 36%… Then Turkey’s political power will increase significantly.

This could be a serious game-changer…

Yes, and we’re still continuing. I’ve acquired four or five properties through this system. Others have also started implementing it. Everyone who sees the benefit is getting involved. For example, I purchased this plot of land for 500,000 pounds; the bank immediately said, “I can give you a three million pound loan.” Because its status has changed.