Chemical analyses of pottery and glass shards, painstakingly recovered from Brahe’s laboratory, have shown concentrations of nickel, copper, mercury, lead, gold, and, most intriguingly, tungsten—an element first identified in the late 18th century.

Tycho Brahe, born in 1546 in what is now Sweden, is celebrated for his meticulous astronomical observations, including the discovery of a supernova in the Cassiopeia constellation and documenting irregularities in the Moon’s orbit—all accomplished without the aid of a telescope, which was invented in 1608. Yet, Brahe’s pursuits extended beyond the celestial sphere; he was an alchemist, following in the formidable footsteps of the German physician Paracelsus. In his quest to develop cures for the myriad maladies of the Medieval era, Brahe engaged in the alchemical practice of melting and mixing rare metals.

One of Brahe’s most notable concoctions was a plague remedy, reputedly administered to Emperor Rudolph II, composed of over sixty ingredients, including opium, iron vitriol, and snake flesh. Such recipes are rare relics of the time, as alchemists guarded their work with the secrecy of master craftsmen.

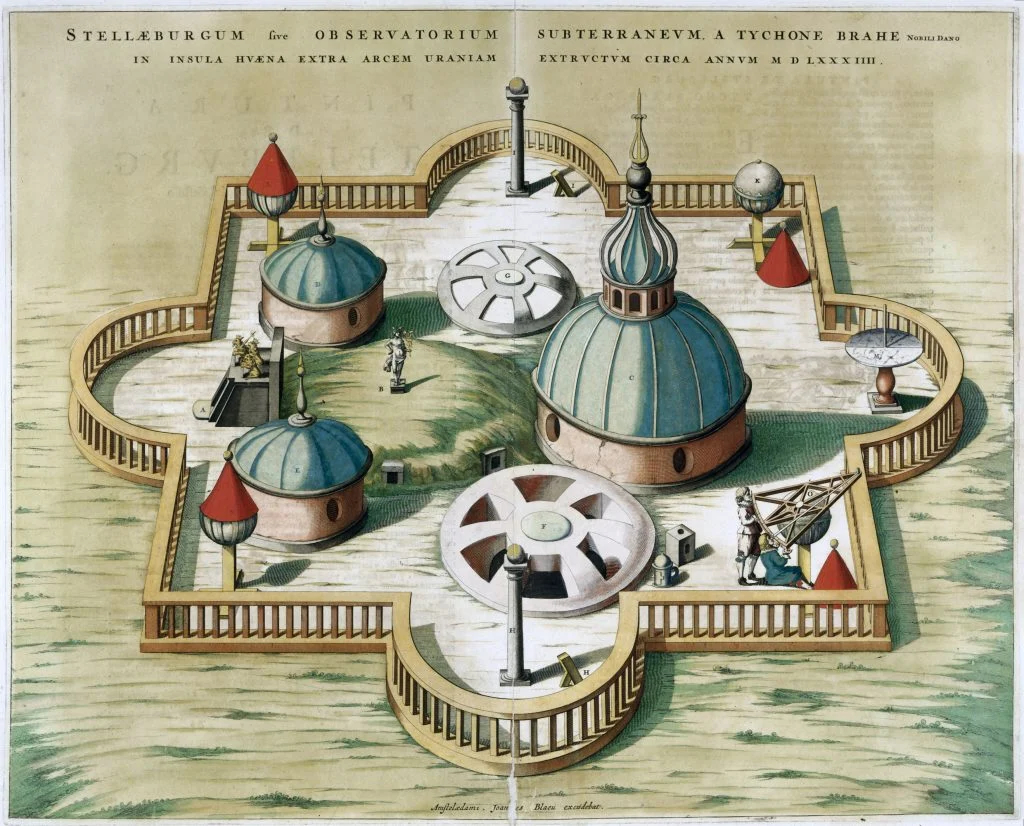

With written records scarce, historians have relied on the meticulous arts of archaeology and chemistry to reconstruct Brahe’s enigmatic endeavors. Though his laboratory in Uraniborg, Sweden, was dismantled shortly after his death in 1601, late 1980s excavations unearthed shards of pottery, glass, and other alchemical paraphernalia used by the Danish savant.

A 2024 chemical analysis of these artifacts, conducted by University of Southern Denmark professor Kaare Lund Rasmussen and National Museum of Denmark curator Poul Grinder-Hansen, has yielded both expected and unexpected findings. Predictably, high concentrations of gold and mercury were present—metals prized in Brahe’s time for their purported healing properties. Other elements such as nickel, zinc, and lead, which do not appear in Brahe’s surviving writings, are likely byproducts of the alchemical reactions he orchestrated.

The real surprise was the detection of tungsten, an element naturally found in minerals like scheelite, ferberite, and hübnerite. Tungsten was first identified and described by Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele almost 200 years after Brahe’s demise. Rasmussen and Grinder-Hansen are left pondering how tungsten found its way into Brahe’s alchemical repertoire. Their study, published in the journal Heritage Science, suggests that Brahe might have isolated tungsten without recognizing it.

An alternative, albeit less probable, theory posits that Brahe might have been influenced by earlier, undocumented accounts. German mineralogist Georgius Agricola’s 16th-century diaries mention a peculiar byproduct formed during tin smelting, which could potentially be tungsten.

“Perhaps Tycho Brahe had heard of this and was aware of tungsten’s existence,” Rasmussen mused in an interview with Phys.org. “But this remains speculative. We cannot confirm this based on the analyses we’ve conducted. It remains a tantalizing theoretical possibility for the presence of tungsten in our samples.”

The revelations from Brahe’s laboratory not only illuminate the depths of Renaissance alchemical practices but also underscore the serendipitous nature of scientific discovery—a testament to the enduring quest for knowledge that transcends centuries.