How did an artist who stands against the art market manage to become “The artist of artists”? Tiraje’s story is one of resilience, filled with betrayals, solitude, and a profound resistance to the world of art itself.

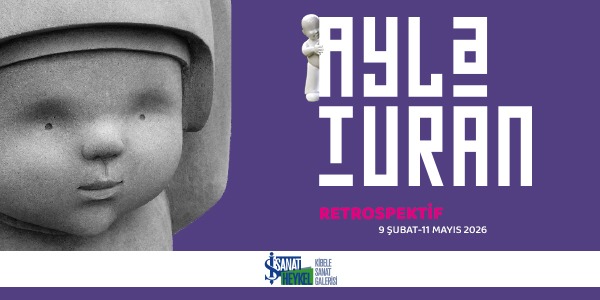

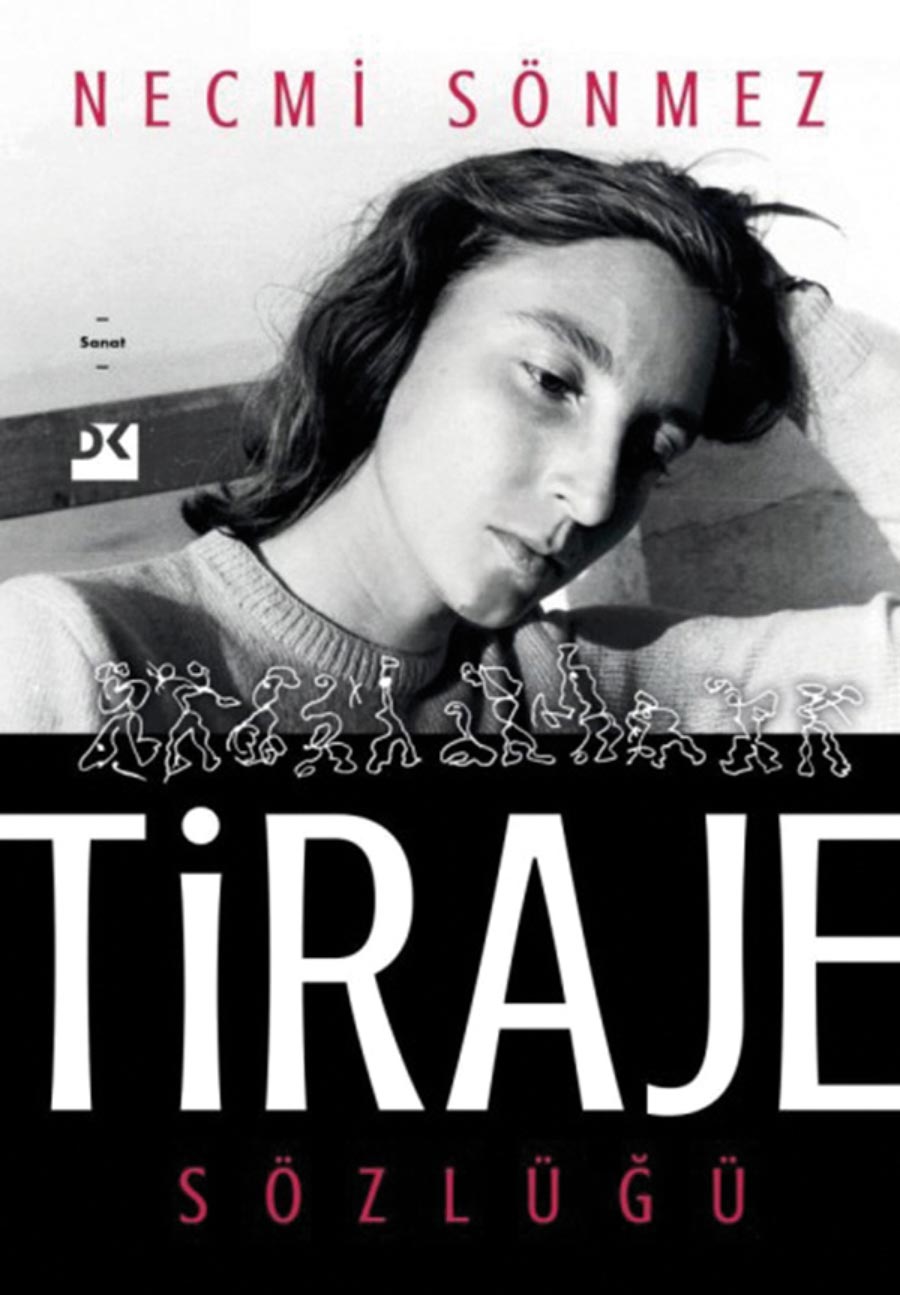

Dr. Necmi Sönmez’s artistic journey, which began with the Fahrelnissa Zeid Dictionary and İlhan Koman Dictionary, reaches its peak with the Tiraje Dictionary.

The Tiraje Dictionary explores not only Tiraje Dikmen’s identity as an artist, but also how her resistance to life and her art shaped her existential stance. One of the most defining aspects that makes her the “artist’s artist” is her distance from the art market and dealers. How did an artist who stands against the art market manage to become the “artist’s artist”? She challenged the traps of the art market, weaving her own cocoon where she could exist. That was Tiraje. While her Persian name, meaning “Rainbow,” may seem contradictory when placed alongside her predominantly black-and-white works, it actually holds the key to understanding the layers of her life and art. Traveling between Paris and Büyükada, this unique painter, who drifted between times and spaces, created her own world, intertwining her art and life in an inseparable way.

The depth in Tiraje’s black-and-white patterns reflects her sensitivity to social issues, showing that as a solitary artist, she is both an individual and collective storyteller. Tiraje’s paintings are not just objects of art; they embody life itself. At first glance, the contrast between the black-and-white works and her name, which means “Rainbow,” may appear contradictory, yet this contrast mirrors the layers of her life.

Tiraje’s Art Deco-style family villa on Büyükada, its colorful garden extending to the Sea of Marmara, and the dynamic art world of Paris—these places were pivotal in shaping both her personal and artistic journey. Yet, for Tiraje, spaces were not merely physical realms; they were cocoons where the past and present, memories and dreams intersected. Dr. Necmi Sönmez meticulously examined how these spaces reflected in the artist’s works and unveiled how Tiraje transformed memory into an art form. Her pieces, oscillating between figuration and abstraction, encompass a wide spectrum, from societal events to personal memories. From the Algerian protests to the Halabja massacre, from Paris’s revolutionary atmosphere to Büyükada’s tranquility, Tiraje’s art stands as a silent record of social witnessing. Dr. Sönmez’s careful research reveals that these works are not just pieces of art, but also memory objects.

Tiraje’s life is a narrative of intertwined loneliness and resistance. Even 11 years after her death in a nursing home, unresolved inheritance disputes and missing artworks serve as reminders of both the artist’s personal complexities and the contradictions of the art world. In this book, you will read about Tiraje’s family dynamics, her defiance against the art market, her stance against betrayals, her loneliness in the art world, and her silent struggle.

These are what remain from the Tiraje Dictionary, but they are not enough. So, Dr. Necmi Sönmez answers them as well.

I’d like to start our conversation with the name itself—an intriguing and beautiful contradiction. How do you interpret the contrast between Tiraje’s predominantly black-and-white works and the meaning of her name, which signifies “rainbow”?

This contrast occurred to me while writing the book. Her life was like that too—the difference between the ground and upper floors of her mansion on Büyükada was immense. I observed the same thing in her studio in Paris. Your question reminded me of something: I was surprised when I saw her descending the stairs of a studio untouched for 20 years, wearing a stunning Chanel suit. But perhaps that was just Tiraje’s way of life, as if she moved between different times. So, I don’t actually see this as a contradiction for her. She also enjoyed delving into details from thirty or forty years ago when she spoke. I’ll never forget the time she described the beauty of Aliye Berger’s hats to me—down to the ribbons and colors—as if she had seen them just the day before. I couldn’t resist asking how she remembered such details. She simply said, “The eye never forgets.” That was the way she spoke and lived.

Was there anything particularly difficult, thought-provoking, or even upsetting while writing the book?

We had been having conversations since the early 2000s. Many topics came up—Lévy, Istanbul, the struggles of the Paris art scene, endless inheritance disputes, family conflicts… She would say, “You can write about it after I die. Let it be for now.” But when writing the book, these topics suddenly became issues that needed to be addressed. It was very difficult to decide how to approach them. I realized that time itself was standing before me like a locked door. How was I supposed to open that iron door? Portraying Tiraje in a way that was true to her, without simply imitating her, was no easy task. She was such a perfectionist that she would surely find a flaw, a missing detail.

Tiraje described her home on Büyükada as a “cocoon,” which suggests an emotional connection to the space. If we compare her life in Paris and Büyükada, what aspects of her personality and art did these two places reveal?

She left her magnificent studio in Paris when her sister put their Büyükada mansion up for sale and fought fiercely to save her childhood home. The first quarter of her life was spent in Büyükada and Şişli, between 1946 and 1985 in Paris, and from 1985 onwards in Büyükada. I see this as a representation of three distinct periods in her art. The places she lived deeply influenced her work. Whether in Istanbul or Paris, she followed her own path without conforming to artistic trends or movements of the time, which meant she walked a rather solitary road.

In the book, you elaborate on the idea of Tiraje as a “painter’s painter.” Do you think this term applies not only to her work but also to her approach to art?

In art history, the term “painter’s painter” refers to artists whose work is primarily admired by other artists rather than the general public. Everyone knows Kandinsky and Paul Klee, but few recognize Johannes Itten, who lived in the same era. Warhol and Lichtenstein are household names, yet Philip Guston is known mostly to art enthusiasts. Similarly, Tiraje was a painter recognized and followed by a select circle rather than a broad audience. She developed a unique, deeply personal visual language that oscillated between abstraction and figuration. The dynamism in her paintings and drawings was both mesmerizing and infused with a kind of mystical devotion. This distinctiveness made her works stand out among hundreds or even thousands of others, which is why I felt the need to describe her in this way.