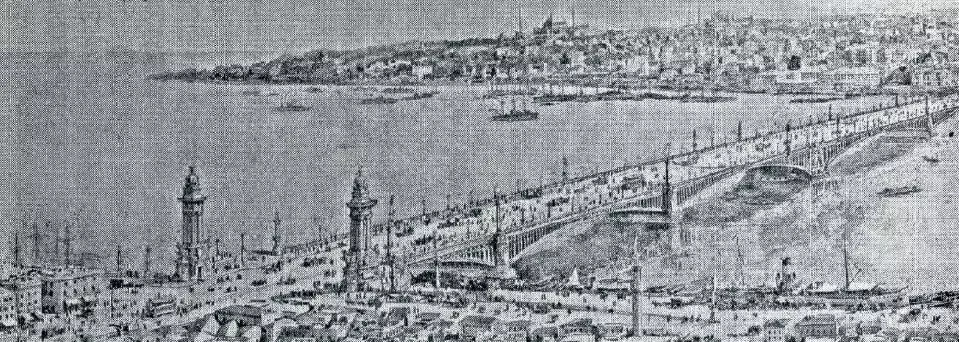

Since the beginning of the 1800s, the reorganisation of Istanbul, like European cities, has been one of the main agendas of the state. For many years, Ottoman administrators dreamed of constructing a capital city with organised streets and boulevards, replacing wood with masonry construction that would resist fires, and providing regular municipal services for more organised city life. The movement of change in the city was not planned, resulting in its spread over a long period of time and being limited to certain areas. While this unplanned transformation was not ideal for urbanisation, it contributed to the city’s appeal to architects and investors. The construction of buildings in various styles and at different times has created a multi-layered and colourful architectural environment in Istanbul, setting it apart from European cities.

In addition to many buildings with different styles and functions that were created by different architects throughout history, dozens of projects could not be realised due to unplanned urbanisation movements and remained only in dreams. Projects that once adorned the dreams of sultans, state dignitaries and architects were forgotten on the dusty shelves of archives. Some cultural and artistic structures were part of these projects. Although many museum projects were prepared during Abdulhamid II’s reign, none were realised.

Ayşe Sultan, the daughter of Sultan Abdülhamid, recalls with fondness her time at the Yıldız Palace. She recalls how her father had a private apartment where he kept family heirlooms, which he proudly displayed in showcases. This created a mini museum within the palace, which was truly remarkable. If we look at the watercolour projects currently exhibited at the Painting Museum in the Crown Prince’s Office of Dolmabahçe Palace, we can see that Sultan II. Abdulhamid had a desire to establish a museum within the palace. Unfortunately, he was unable to bring this project to fruition.

It is unknown who prepared these projects, consisting of two drawings and dating back to the 1880s. The initial illustration displays the outside of the structure and outlines the various sections that the museum will include. The subsequent illustration showcases the internal layout of the museum, specifically highlighting the significant gallery that will house the portraits of the sultans.

According to the architectural drawing projects, this museum to be built within the Yıldız Palace was to consist of ten sections. The first section will feature precious and ancient coins, various jewellery and jewelled items; Precious metal and marble objects will be exhibited in the second section, sultan portraits in the third section, valuable European porcelains in the fourth section, and diplomatic gifts sent to Sultan Abdulhamid from all over the world in the fifth section. In the sixth section, works of antique value made of bronze and silver will be featured, in the seventh section distinguished examples of traditional Turkish arts, such as carpets, rugs and miniatures will be exhibited, in the eighth section there will be Saxon and Northern European porcelains, in the ninth section calligraphic works and Bohemian crystals, and finally in the tenth section. On the other hand, there would be ceramics and valuable items from China and Japan.

Apart from this project, which is not yet known why it could not be realized, as Ayşe Sultan painfully mentioned, all the valuable items and family heirlooms that Sultan Abdulhamid II brought together during the looting of Yıldız Palace were also destroyed and an important memory was lost. After this museum project (architectural drawing), the author of which is unknown, it is understood that Sultan Abdulhamid wanted new museums to be established within the palace and in Istanbul, and he had projects prepared one after another.

The individual who was responsible for designing the majority of these projects is the same person who arrived in Istanbul to construct the Agriculture and Industry Exhibition Palace. The palace was planned to be constructed in Şişli in 1893, and the architect behind it was Raimondo D’Aronco, an Italian.

Unfortunately, his first project in the Ottoman capital was not realized due to the devastating earthquake that hit Istanbul on July 10, 1894. After that, Italian architect Raimondo D’Aronco was commissioned to design the later projects. Although D’Aronco was unable to build the exhibition palace in Şişli, he remained in Istanbul for many years and became one of the most productive architects of Abdülhamid Istanbul. It is evident from a letter he wrote on August 14, 1914, that D’Aronco intended to go to Italy for the house he had built in Turin, but his departure was delayed due to the museum project he was requested to work on.D’Aronco writes in his letter:

I was supposed to leave at this hour, but I faced some issues and setbacks that will keep me here for another 15 days. Just when I was about to ask permission from the sultan to leave, he urgently asked me to do a museum project. This has happened five or six times before and I’m not sure what to do. If I oppose it, the house’s implementation might be delayed even more.

Among Raimondo D’Aronco’s architectural projects preserved in Udine is a museum project dating back to 1896. Although it is not recorded where this museum was planned to be built, it is known that D’Aronco also worked for the Weapons Museum that was planned to be built in Nişantaşı between 1900-1904. When we look at the projects prepared for the Weapons Museum, it is seen that all the projects are prepared in a single prototype, and this museum project dated 1896 has a different structure from the others. Therefore, this project may have been prepared for the museum planned to be established in Yıldız Palace.

A second museum proposal and the idea of establishing a Weapons Museum came from Ahmed Muhtar Pasha, who also reorganised the Military Museum and established the Janissary Museum in Sultanahmet. Ahmed Muhtar Pasha, who has published many works on the history of war, saw how antique weapons and military materials were exhibited during his visits to Germany and that these works were used as propaganda material. On his return to Istanbul, he convinced Abdülhamid II for the establishment of a new weapon museum, while establishing a commission to construct the museum and he began gathering scattered old weapons under one roof.

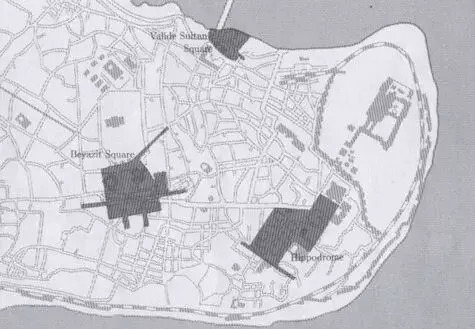

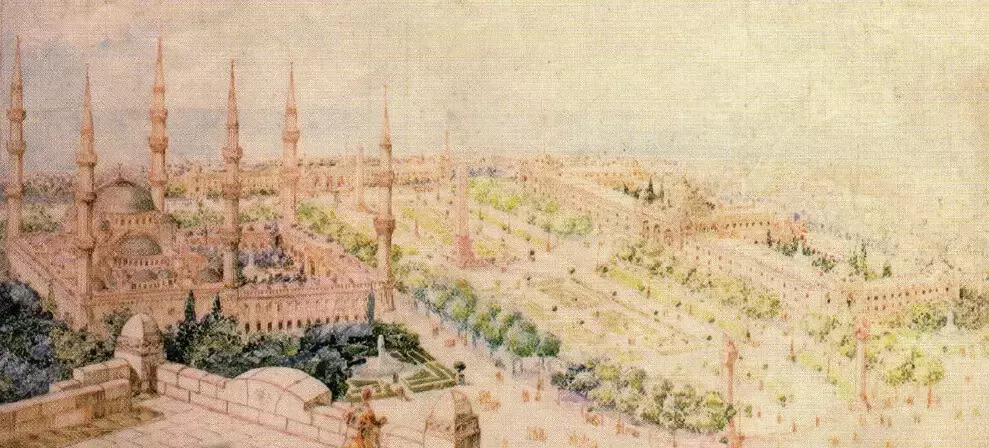

The commission first opened an exhibition of antique weapons collected in the Silahhane of Yıldız Palace. They were considering constructing a large, detached building for the Weapons Museum or repairing one of the old buildings and allocating it to the museum. As it can be understood from the projects of architect Raimondo D’Aronco preserved in the Udine State Library, the construction of an independent Weapons Museum apart from the exhibition in Yıldız Palace was planned, and Nişantaşı was chosen as the venue. In his writings, D’Aronco stated the museum was planned to be built in Nişantaşı. He designed multiple architectural projects between 1900 and 1904, including one for a museum in Nişantaşı. However, none of these projects were ever realised.

As per the recollection of Fausto Zonaro, the painter of the palace during Sultan Abdulhamid’s reign, the Weapons Museum received project proposals from multiple architects, including D’Aronco. After due consideration, Vedat (Tek) Bey, a prominent figure of the National Architecture movement, was selected to execute the project. As seen in a photograph preserved in the Rare Works Library of Istanbul University, Antoine Perpignani, the architect of the French Embassy, was one of the individuals involved in the Weapons Museum project.

The office of Perpignani, who has designed and built many housing projects, especially in the Beyoğlu region, and many of the buildings he built have survived to the present day, was located in the Saint Pierre Han in Galata. The stamp on the photograph of the project indicates that Saint Pierre Han is the address of Perpignani. As seen in the project, Perpignani had prepared a project in Art Nouveau style in accordance with the tastes and preferences of the period. Painter Fausto Zonaro writes the following in his memoirs about the Weapons Museum, which could not be realized:

I received a call from His Majesty and went to meet Mahmud Şevket Pasha, a distinguished officer, at the Chief Clerk’s office. We were both summoned to declare our will. After waiting for a while, the Chief Clerk informed us that the mansion on the Ortaköy slope would be overhauled and turned into a museum for ancient weapons.

Pasha was in charge of the technical discipline as the manager, while I took care of the aesthetics as the manager. The architects of the city were to compete for the design of the museum building. But, before that, arrangements had to be made in the mansion under consideration.

Five local architects presented their designs, with Vedat Bey, the architect of the Ottoman Post Office in Istanbul, emerging as the winner. His design for a useful public structure would enrich the capital city. However, the project faced delays due to concerns about the cost. Nonetheless, I believe that the most important thing was to start the project. The Turin Armory, which was initially located in one or two rooms of the Royal Palace with only a few weapons, is now a vast building and one of the most interesting arsenals in the world. If built, the Istanbul Arms Museum, located next to the Sultan’s palace, could become one of the leading arsenals in the world.’’

Vedat, the architect, had a project that Zonaro had praised as the chosen one to be built. However, it failed to enrich the capital city as Zonaro had hoped. He mentioned that there were two lands under consideration for the Weapons Museum. The first one was the Armenian Cemetery located behind the Topçular Barracks, and the other land is unclear. Zonaro also writes about this failed project saying that:

During our recent commission visit to the proposed site for the impressive Weapons Museum building, we examined two potential locations. One was the Armenian Cemetery located behind the barracks on the right side of the road leading to Nişantaşı, and the other was opposite Taşkışla, currently being used as an armory, on the stony road overlooking the entire Nişantaşı area. Despite being late, I walked slowly to enjoy the breathtaking view. However, I was surprised to find the door to the Weapons Museum closed. Initially, I thought it was closed due to it being a Friday, but that was not the case. I wondered why the door was closed at that time.

Feeling anxious, I retraced my steps and went to Lieutenant Mustafa, who was in charge of the relevant commission. As I entered the hanagar, the Lieutenant signaled me to keep quiet and revealed that His Majesty the Sultan had received a confidential report from a journalist, warning about a possible uprising in the museum, which was linked to the Young Turks. All the antique weapons that we had sorted and cataloged were stored in a warehouse, and the museum was closed. One of the commission officers was sent to Germany for some official work, while His Excellency Mahmud Şevket Pasha was appointed as a governor in Anatolia and had already left. As a result, the Museum of Ancient Weapons was disbanded and never mentioned again.

As noted by Zonaro in his memoirs, numerous museum projects that were planned during the Abdulhamid era never came to fruition due to journals, financial difficulties, or earthquakes. These museums, which were once the aspirations of many, are now merely projects that have been filed away. If these projects had been completed and the envisioned museums had been constructed with the collections in question, today we would undoubtedly have many other museums with a rich history, similar to the Archaeology Museum. This would have also given us the opportunity to view equally well-preserved and rich collections.