Why do we collect? Is art collecting difficult? Is being a collector a sign of wealth? What are the qualities of a good collector? Are there collectors in Turkey who are recognized on a global scale? We spoke with art historian Oğuz Erten about collecting—a practice that has evolved throughout the long journey of humanity.

Why do people collect things? Why do they want to build collections?

The answer may surprise you, but it goes back to the era when humans lived in caves. According to art historian Oğuz Erten, the story of collecting starts right there.

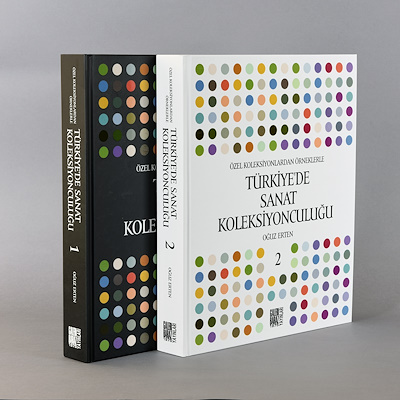

Humanity has come a long way since the cave era. Yet the habit of collecting, which began with an interest in beauty, hasn’t changed much. However, the form of collecting has evolved significantly. Being a collector—especially of art—is no easy task. It requires curiosity and passion. Erten emphasizes that it’s a long journey. As an art historian, he has closely observed people driven by this passion. While writing his two-volume book Art Collecting in Turkey, the result of years of research, he had the opportunity to get to know many collectors more intimately. That’s why he is one of the best voices to explain this subject. We spoke with Erten about the evolution of interest in beauty and rarity throughout human history, and the story of collecting in Turkey.

Why do people collect? How has the act of collecting evolved over time?

This passion dates back to the time when humans lived in caves. There was a division of labor: men went out to hunt, women stayed in the cave. The story begins with the man’s instinct to bring back and share interesting and beautiful things he saw outside. This may explain why a majority of collectors have historically been men. Interest in what is beautiful and rare evolved over centuries into collecting practices. It started with stones and seashells, then expanded to rare animal skeletons and plants from distant lands. We trace the beginning of art collecting to ancient Rome, where Roman generals and emperors began collecting Greek sculptures. Many of the obelisks in European cities—including Istanbul—were brought from Egypt as part of this desire to possess rare and beautiful objects.

How did painting collections begin?

Transporting large sculptures and icons was difficult. But in the 15th century, the Dutch began producing canvases from sailcloth, making paintings more portable. This made buying, selling, and collecting artworks more feasible. Still-life painting, for example, emerged from the desire to see summer fruits during winter—an indication of wealth at the time. With the Renaissance, collecting became a competition among the elite. Collectors displayed their power through their collections. This competition also contributed to the transformation of craftsmanship into fine art, as the signature of the artist became important. As signatures gained value, artworks became rarer and more desirable. Collectors wanted to own works that held such unique stories.

How did collecting begin in our region?

After conquering Istanbul, Sultan Mehmed II invited the painter Bellini and the sculptor Costanzo de Ferrara to his court. Bellini painted Mehmed’s portrait, and Costanzo cast a medallion. Bellini also painted janissaries and other palace residents. Mehmed saw himself as the heir to the Roman Empire and wanted to express that through culture. However, his son Bayezid II rejected this vision. He sold his father’s portrait to Italian merchants in Galata. That portrait is now housed in London’s National Gallery. What followed was a conflict between innovators who valued Western art and conservatives who rejected it. By the 16th century, we see pashas collecting calligraphy and sultans building libraries. Later, some pashas began hanging paintings in their homes.

How did palace collections develop in the Ottoman Empire?

In the 18th century, the Ottoman Empire experienced the Tulip Era, shifting from “we know everything” to “what’s happening in the world?” Pashas were sent to observe Western life and brought back objects and ideas. The telescope entered the Ottoman Empire during this time. Western palaces and lifestyles were introduced. During Sultan Abdülmecid’s reign, the first Western-style pavilion was built in Topkapı Palace, followed by the construction of Dolmabahçe Palace. This introduced a new question: “What should we hang on the walls?” Pashas like Şeker Ahmet Paşa, who had received art education in Europe, were tasked with purchasing paintings for the palace. He went to Paris to buy artworks, effectively creating the palace’s first painting collection. This inspired other pashas to begin their own collections. Later, Osman Hamdi Bey founded archaeological museums, further strengthening the culture of collecting. Art was being made, exhibitions were being held, and art criticism appeared in publications. Art schools were founded. All of this led to increased interest in collecting. By the 1950s, private galleries emerged and developed their own collector circles.

Oğuz Erten: Collectors Can Pay Incredible Sums for a Single Work

How should collecting be categorized in light of this historical journey?

There’s a saying: “Every collector collects themselves.” No matter who you are, you can’t buy something outside your taste. Your knowledge, cultural background, and intellectual framework determine what you see. In Turkey, collecting often begins due to social pressure. Friends and acquaintances talk about art, sparking interest, which turns into curiosity, and then into learning. You can’t be curious about something you don’t even know exists. Once you start learning, you discover an incredible world. Collector Ömer Koç describes collecting as an addiction—an incurable one. But it’s a beautiful addiction, one that makes you feel truly alive. That’s why collectors around the world can pay astronomical sums for a single artwork. They make outrageous purchases.

Is art collecting an investment?

That’s the other side of the coin. If you view it purely as an investment, you start to lose the joy it offers. You stop appreciating the aesthetic experience. That’s why collectors are often divided into two groups: those who collect for joy and those who collect for investment. In my 25 years in this field, I’ve seen that those who collect for pleasure often gain more—artistically and even financially—than those focused only on profit.

Has art collecting been fully understood in Turkey?

It’s a journey. 25 years ago, art collecting was confined to a small elite. By 2025, we see a very different picture. More museums have opened, and the number of collectors has increased. It’s still not enough, but we’ve come a long way and the journey continues.

Are new value systems—like crypto—changing collecting?

I see crypto art purchases more as marketing tactics than true collecting behavior. They’re attempts to attract attention to new financial systems. These purchases aren’t widespread, and I don’t think they’ll dominate anytime soon. Art and its history have deep traditional roots. This field values the past. So I don’t foresee these practices being widely accepted. They’re contrary to the spirit of collecting.

When did the Turkish art market begin to take shape?

You could say it started during the Özal era. There were collectors before, but they weren’t businesspeople. After 1980, business leaders began collecting art. Sakıp Sabancı was a major exception and a role model. After him, others followed. Auctions became more common. We moved from house auctions to hotel ballrooms. Even though auctions went online during the pandemic, those grand hotel auctions were unforgettable. Everyone followed the news of who bought what. That competition fueled the desire to collect.

Is collecting seen as a sign of wealth? Is that a fair perception?

Not really. Not every collection has a high monetary “value.” There’s a confusion in Turkey between “value” and “worth.” In the West, “value” refers to artistic merit, not price. A work’s value comes from the quality and historical significance of the artist’s creation. Its price follows from that. In Turkey, “value” is often interpreted as monetary. This misunderstanding leads people to equate collecting with wealth. But sometimes the most valuable artworks have little monetary worth—and vice versa.

To prove this, when we founded Bozlu Art Project in 2013, we created a collection called Artists’ Studios. We asked artists for objects from their studios: brushes, palettes, clothing. Now the collection includes over 70 pieces. Some examples: Mübin Orhon’s palette, Fahrelnissa Zeid’s brush, Utku Varlık’s paint-covered shirt. We didn’t pay for them; the artists gifted them. A major auction house called this collection “priceless,” because no one had thought to build a collection this way. That’s the alchemy of art: the idea behind a collection matters more than the price of the objects.

Oğuz Erten: If There’s No Framework, It’s Hard to Call It a Collection

What should collectors keep in mind?

Just like people have personalities, good collections need character. The first step is to define a framework. One person may focus on seascapes, another on children’s portraits, another on calligraphy. The key is to stay within that framework. If the value of the collection as a whole is greater than the sum of its parts, it’s a good collection. If there’s no clear concept, it’s just a group of random objects. That’s what we mean by “every collector collects themselves.” If your thoughts and interests are scattered, so will your collection be. But if you’re focused, your collection will reflect that clarity.

But we live in an age of ambiguity. How do collectors stay within a framework today?

A collection is the result of the collector’s personal attention and interest in certain objects. The more effort and time you invest, the more meaningful it becomes. If today is the “age of uncertainty,” and we are surrounded by complexity, then a collector might choose to focus on exactly that chaos and create a collection around it. The collector’s intellectual background matters. To understand the present, we need to look at the past. The better we understand history, the more clearly we can define today’s world—and the better we can shape a meaningful collection.

Do we have collectors in Turkey who are recognized on a global level?

This is a two-part answer. Yes, we do have collectors who own works highly valued internationally. Some collectors in Istanbul possess major classical artworks—by Monet, Degas, Picasso. So yes, we have collectors closely following global art.

The second part is about how Turkish collectors approach Turkish artists. Many are willing to pay only so much before thinking, “I can get something better from the West.” But that’s the wrong attitude. Take China as an example. Until the 1980s, Chinese painting wasn’t prominent globally. But once China underwent economic transformation, wealthy Chinese began investing in their own artists. Western collectors noticed, and Chinese art soared in value. If we don’t support our own artists, the West won’t either.