When Nadia Myre arrived for her residency on an island in a man-made lake in central France, she began by making her own charcoal. After finding trimmed willow branches at a local store, she created a small fire on the island to produce the charcoal, which not only served as a medium rooted in the local environment but also allowed the Montreal-based Algonquin artist to “to enter my own ideas and personhood into that space,” as she explained.

Myre used the charcoal to sketch designs for two photographic works featured in her solo exhibition, “Ropes & Lines,” at CIAP Vassivière, an artist residency and exhibition space on Île de Vassivière in France’s Limousin region. After the Fire (2024), which depicts a bird in flight, was captured using a “quasi-pinhole” technique on photographic paper before being scanned and printed. Reduced to a Few Kilos of Ash (2024), which resembles the remains of a boat hull, involved scanning the charcoal sketch and then digitally inverting it before printing.

As a member of the Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation, Myre’s first solo show in France can be seen as an anti-colonial statement, referencing the 200-plus years of French colonization in Quebec before it became a British colony and eventually a Canadian province. However, Myre explained that the colonial history didn’t directly influence her preparation for the exhibition. Still, the colonial dynamics of Canada, especially in Montreal, where English and French communities are divided, are ever-present in her work. She remarked “The French are slower than the English to awaken to their histories,”

Another significant piece in the show, Still Too Heavy to Carry (2024), consists of strands of hundreds of handmade ceramic beads suspended by a rope-pulley system, rising about eight feet in the air. These beads, inspired by wampum—beads significant to Indigenous peoples of the Eastern Woodlands—are rendered in muted shades of white and off-white. Myre noted that their simplicity references the French practice of making their own wampum to trade with Indigenous people, though these European-made beads were never valued by the Indigenous communities.

Despite the beads not being part of her own cultural traditions, Myre uses them as a form of mourning, honoring those lost due to the destructive effects of colonization. She noted the tragic impact on Indigenous peoples, who are often unable to live sustainably off the land due to ecological degradation, leading to a crisis of mental health and suicide.

Myre also explores this theme in [In]tangible Tangles (2021), a series of images of moccasins from the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s archive. The shoes, often displayed with their soles facing the camera, evoke a haunting image of absent bodies. Some were acquired as early as the 1860s, while others entered the museum much more recently, raising questions about their acquisition and the colonial violence behind it. Many of the shoes belonged to children, reminding Myre of residential schools in Canada and the US, where Indigenous children were forcibly separated from their families to be assimilated into settler society, often facing abuse and death.

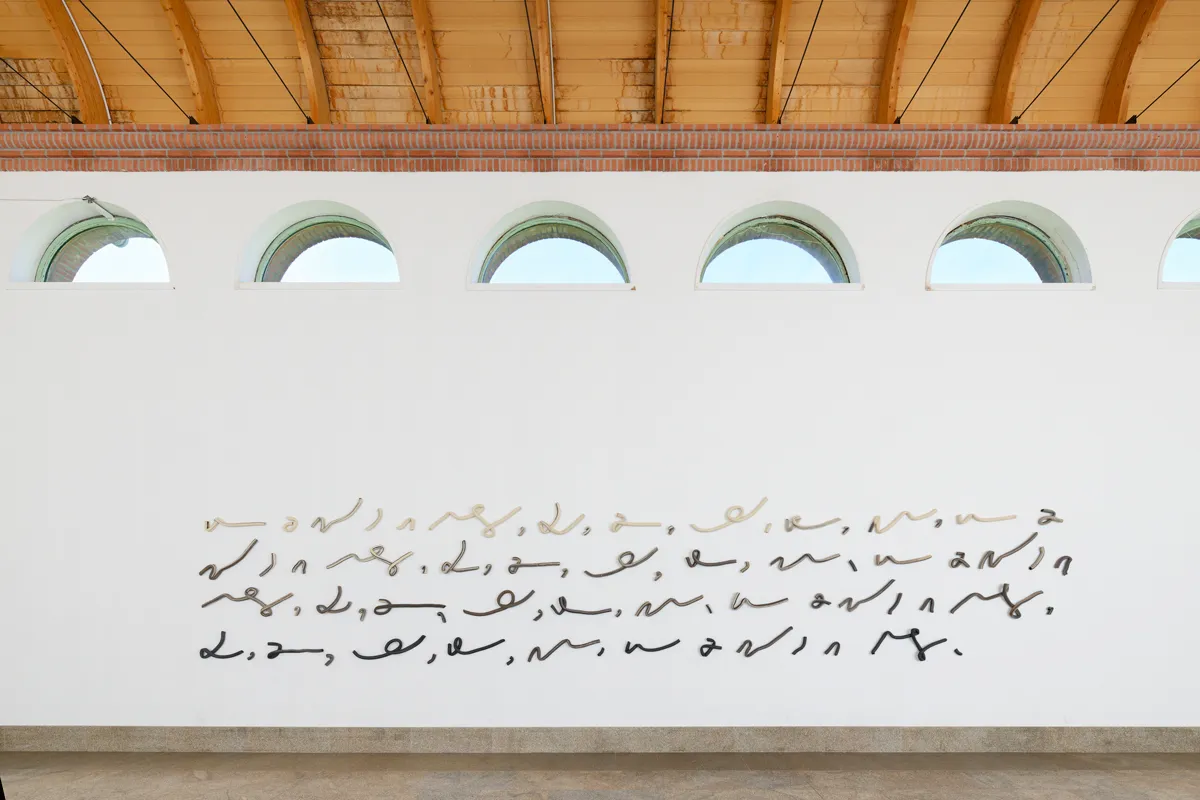

These new works build on Myre’s ongoing exploration of colonialism, such as her Indian Act (2000–02) project, in which participants beaded over copies of the Canadian Indian Act—a law that determines who is recognized as Indigenous. Myre also contributed to CIAP Vassivière’s 2022 group exhibition Lines of Flight, which examined colonial exchanges between Indigenous Canadians and the British Empire.

CIAP Vassivière’s director, Alexandra McIntosh, emphasized the importance of this exhibition, noting that it offered local visitors an “openness” to engage with difficult topics in a new context. “It was super important to provide an opportunity for an Indigenous artist from North America to address these questions in a very different place, and to also ideally open our perspective on them in the context of Vassivière and France,” McIntosh said.a