Museums have taken on the responsibility of reflecting on everything that is happening in society. They have become a platform for various activities and cannot escape the latest events in the world. Instead of taking to the streets, activists have started to choose museums as their preferred location for protests. This has elevated museums to a new level of importance and meaning. Kristy Robertson, in her book ‘Tear Gas Epiphanies’, argues that museums become targets for various actions, both connected to and distinct from large movements, in a challenging environment. The interventions at and outside the museum range from awareness of anti-racism initiatives, battles over representation, resistance to gentrification, and climate change. After a decade, museums play a collaborative role in political action and social justice. In a way, maybe they are becoming part of society with these protests. Or is this a new phase for museums to understand and act differently?

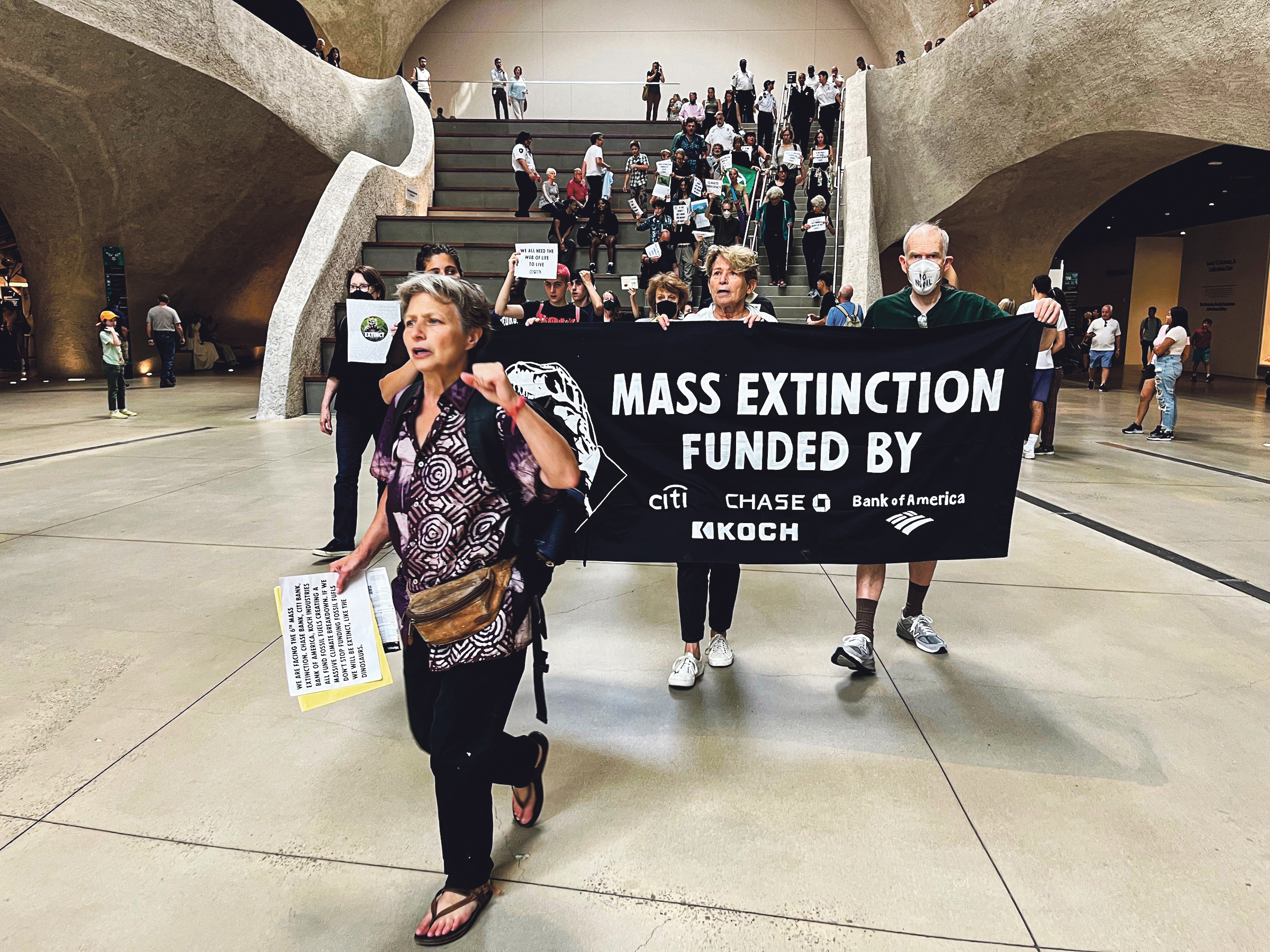

People protest inside or in front of museums to bring attention to the climate crisis and social injustice. Despite some controversy surrounding these protests, there has been a shift in how people protest, with more peaceful and non-harmful means being used. For instance, a recent protest at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) aimed to raise awareness about the impact of the fossil fuel industry on climate change and extinction while not causing any damage to the museum’s artifacts. Rather than damaging an artwork, causing damage, the protesting style has changed this time.

Suzanne Macleod in her article titled ‘Civil disobedience and political agitation: the art museum as a site of protest in the early twentieth century’ (2006) focuses on two different kinds of political protests in museums. One of them is Mary Richardson’s attack on Velazquez’s Rokeby Venus in London’s National Gallery in 1914 and the ‘rushing’ and occupation of the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool by the National Unemployed Workers’ Committee Movement (NUWCM) in 1921. According to Macleod,; ‘’in each of these cases, the museum was selected as a suitable site to make a political point, and in both cases, the protestors utilized the space of the museum to further a political cause. These examples may show that a museum as a space has always been the venue of protest, and disruptive protests are nothing new.

Disruptive protests do pay off

Nan Goldin’s protest was held at the atrium of an institution against the acceptance of donations from the Sackler family, who owns the company that makes OxyContin, a prescription painkiller that has contributed to the opioid crisis in America. The protest was led by Nan Goldin, who urged museum directors to remove all associations with the Sackler name. Her efforts were successful, as one by one, museums such as the Victoria & Albert Museum, the British Museum, Dia Art Foundation, the Louvre, and lately, Victoria and Albert Dundee, dropped the Sackler name.

The latest protest at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) is another example of the ongoing demonstrations against controversial figures. The museum’s Dinosaur Wing is named after David Koch, a billionaire who owned oil refineries and was accused of funneling over $100 million to climate-denial lobby groups. Koch also supported right-wing politicians who made climate change a divisive political issue. He served as an AMNH trustee until he stepped down in 2016, amid mounting criticism of the museum’s association with him, although AMNH denied that this was the reason for his departure.

In 2019, Warren Kanders stepped down from his role as vice chairman of the Whitney Museum after the activist group Decolonize This Place protested his ownership of Safariland, a manufacturer of military and law enforcement supplies including gun holsters and tear gas. On the other hand, the same group also protested Brooklyn Museum for not employing African American curators and the news were all around. Years later Brooklyn Museum has changed and has become more diverse.

Today’s protests

Recent protests have mainly focused on climate change. The first incident that sparked the movement occurred in Germany and was led by a faction of Extinction Rebellion called “Letzte Generation.” On October 24th, 2022, two German protesters threw mashed potatoes at a Claude Monet painting titled “Grainstacks,” which was valued at over $110 million. Another incident involved a member of “Just Stop Oil” attempting to glue his head to the famous Vermeer portrait, “Girl with a Pearl Earring,” at the Mauritshuis in The Netherlands. As a result, three people, including another member who glued himself to the wall and poured canned tomatoes on himself and his fellow demonstrator, were arrested in connection with the attack. On November 11, 2022, two members of the Norwegian climate activist group “Stopp Oljeltinga” attempted to glue their hands to the frame of Edvard Munch’s “The Scream” at the National Museum of Norway. On November 15th, 2022, “Letzte Generation” poured what they described as oil all over Gustav Klimt’s painting “Death and Life” at the Leopold Museum. They made this statement to show how new oil and gas wells are a death sentence for humanity.

To better understand the times we live in, we can analyze the paintings that are being targeted. For example, Munch’s “The Scream” portrays the harshness and chaos present in our society, while Gustav Klimt’s “Death and Life” provides an important perspective on the same subject. By looking closely at these works of art, we can gain a deeper understanding of our world.

Representatives from nearly 100 galleries, including the Guggenheim Museum in New York, the British Museum in London, and the Louvre Museum in Paris, have issued a joint statement warning that climate protests put priceless artworks at risk. The statement was released on November 15, 2022.

The German National Committee of the International Council of Museums (ICOM) issued a statement saying that museum directors were becoming increasingly “frustrated” and “deeply shaken” by the threat to art.

Museums still do not know how to compete with these challenges, which is the main question.

Protests have a disruptive effect on museums and make them more aware of the society they are serving. Some museums choose to play it safe by closing their doors, like the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, while others understand that they need to explore alternative financing techniques to adapt to the changing times.

The International Council of Museums (ICOM) has released a statement urging museums to join the fight against climate change. According to ICOM, museums should be viewed as “allies” in efforts to combat the environmental crisis that poses a threat to life on our planet. The statement calls on museums to recognize and share the concerns expressed by climate activists while taking steps to protect their collections.

The museum faces a dilemma: whether to allow protests or seek new ways of expression. However, they are constrained by budget, commitment, ambition, and staff shortages.

It’s not enough for museums to only adopt new financial support techniques; they must also re-evaluate their openness to society and change how they interact.

Turkey’s museums and protests

Museum management in Turkey is quite diverse. While some museums are privately owned, others are partially funded by the government, and some are owned by government entities such as the Fine Arts Directorate, which operates under the Culture and Tourism Ministry. Depending on how museums are managed, they may have a political stance and varying levels of connection with society. This is why it is rare to see museum protests or demonstrations in front of museums in Turkey, as funding sources influence their behavior. However, incidents of censorship are frequently encountered.

Istanbul Modern, which opened at Galataport in 2023 after renovation, seems inaccessible for protests due to its high level of security.

Curator Beral Madra wrote an article in Tasarım Magazine about museology and Istanbul. She believes that with its five-star hotels, skyscrapers, plazas, and galleries belonging to private and public institutions, Istanbul has become the center of an intense international communication network. However, the flamboyant architecture of these buildings is built on a very poor infrastructure and somehow affects the reality of culture and how it develops over time.

Madra also talks about the situation of historical museums, which are an important part of cultural identity. She points out that hundreds of thousands of tourists visit Turkish, Islamic, and state palaces like Topkapı Palace and Dolmabahçe Palace annually. However, except for a few museums that are maintained due to their contribution to the budget, most of these museums belong to the past century. Thus, they are considered dead museums that continue the concept of museology.

Madra’s concept of a “dead museum” is now a reality. Since museums often focus only on tourists and are not actively engaged in society, they can be viewed as stagnant.

If we need to look at the museums from this perspective, in the 21st century, we need more democratic, transparent museums. Hence, these museums need a longer planning span. In her article titled Museums of the Future, “ she said the institutions need to plan 30 years to maintain their visitors and the needs of the society.

Museums in the 21st century strive to embody democratic values, being open to society and facilitating community participation. Their mission, vision, goals, and functions should align with social studies and development efforts. Therefore, museums are expected to act as development agents, encouraging progress and becoming tools that reflect social development.

But there is a reality that we cannot escape; protesting in or outside a museum may mean as a social development. Because it means museum-society interaction and museums can change for society in a way that coincides with their aims.

According to Madra, they must personally participate in the process and request it from the museum. Hence, to become agents of development in society, they should be close to the communities they are serving. This once again leads to financing issues in museums.

One perfect example is Şükran Moral’s Bordello performance. Moral sat at the door of one brothel holding a For Sale sign, then another for an Art Museum. She turns a brothel into a museum and a museum into a brothel. Maybe we did not see this protest art in a museum, but it is definitely about a museum.

However, this is still not what Turkish museums are staging. It is unlikely to see any demonstrations in front of the legendary Archeology Museum or Istanbul Modern. It is clear that museums in Turkey are not a place for public debates or protests. They are closed venues exhibiting artwork, and they are not meant to serve as a forum for political or social discourse.