The traces left by Samih Rifat’s wide intellectual legacy—ranging from translation to photography—are now on view at the Pera Museum in the exhibition “Much Is to Be Done”

When Samih Rifat, one of the most multifaceted intellectuals in Turkey’s cultural and artistic world, passed away in 2007, he left behind a deep imprint in the fields of literature, translation, photography, and the history of thought. Born in Istanbul as the grandson of Samih Rifat, the founding president of the Turkish Language Association, and the son of poet Oktay Rifat, a key figure of the Garip movement, Samih Rifat did not merely inherit a rich cultural legacy—he expanded and enriched it through his own original contributions.Today, Samih Rifat’s photographs, poems, documentaries, and translations bring his unique intellectual world back to life at the Pera Museum. The exhibition, titled A Lot Left to Do: Photographs, Films, Drawings, Poems, Notebooks, Books, and Music, traces Rifat’s intellectual journey, his interdisciplinary crossings, and his poetic sensitivity, offering visitors a rich glimpse into his world of thought and art.

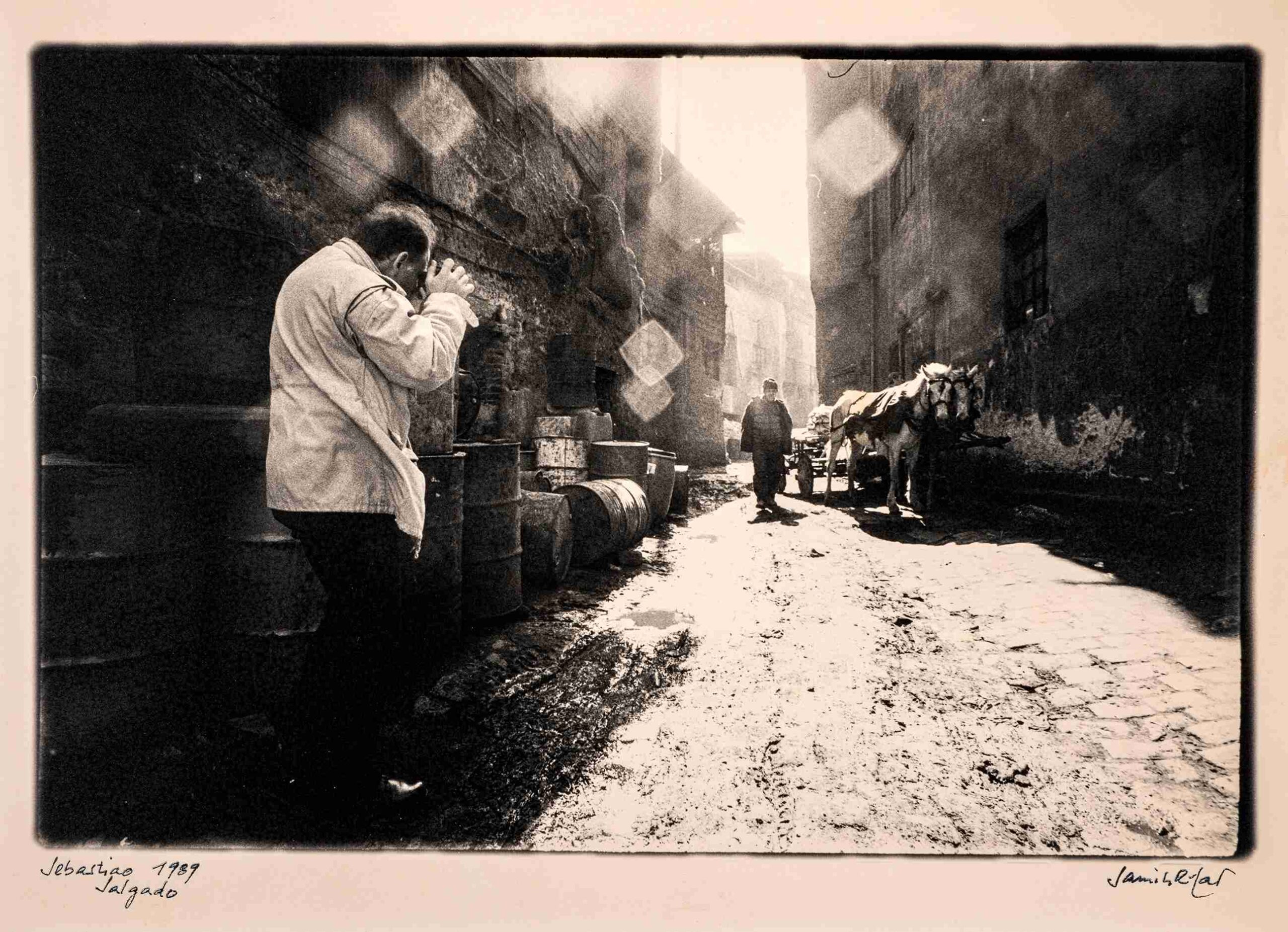

The exhibition is also a tribute project by the Pera Museum, commemorating its 20th anniversary. It honors Samih Rifat, who served as the artistic advisor to the Suna and İnan Kıraç Foundation in its early years and curated major exhibitions for Pera Museum, including those featuring renowned photographers like Henri Cartier-Bresson and Josef Koudelka. Drawing nourishment from both Western and Anatolian art and intellectual traditions, Samih Rifat’s entire creative process—especially his photographs and drawings—is displayed here. His profound engagement with ancient civilizations, his mastery of languages, and his meticulous approach to translation form major sections of the exhibition, curated by Bülent Erkmen, with curatorial consultancy by Serhan Ada and photography consultancy by Esra Özdoğan and Ahmet Elhan. The exhibition also features his documentaries, his relationship with poetry and music, and much more.

As Celal Üster notes in the essay In Pursuit of Lost Beautieswritten for the exhibition catalogue, “Samih Rifat clearly sought poetry in architecture, in photographs, in music—in everything, everywhere. In books, in life, in the lives of others. He chased after the beauty, mystery, and astonishment of poetry.” According to Üster, Rifat, “in a society where almost all values are gradually unraveling, upheld a passion and sensitivity that made life worth living, standing firmly as a true man of culture.”

One of Samih Rifat’s greatest contributions to Turkish cultural life was undoubtedly his work in translation. Through his translations of important literary and philosophical figures such as René Char, Jacques Prévert, André Verdet, Jean Follain, Paul Valéry, and C.P. Cavafy, Rifat enriched the Turkish language. His approach to translation extended beyond linguistic transfer; it was a cultural bridge-building effort. His Turkish rendering of Aristotle’s Poetics—considered the first theoretical work of literature—is a prime example of this ambition. In addition, his translations of writers like Flaubert, Amin Maalouf, Mayakovsky, Seferis, and Valéry opened wide the doors of world literature to Turkish readers. Celal Üster describes Rifat’s translation philosophy by noting, “There is an undeniable kinship between what Samih Rifat wrote and what he translated. More often than not, he chose to translate writers and poets with whom he felt a profound affinity, rather than those suggested to him.”

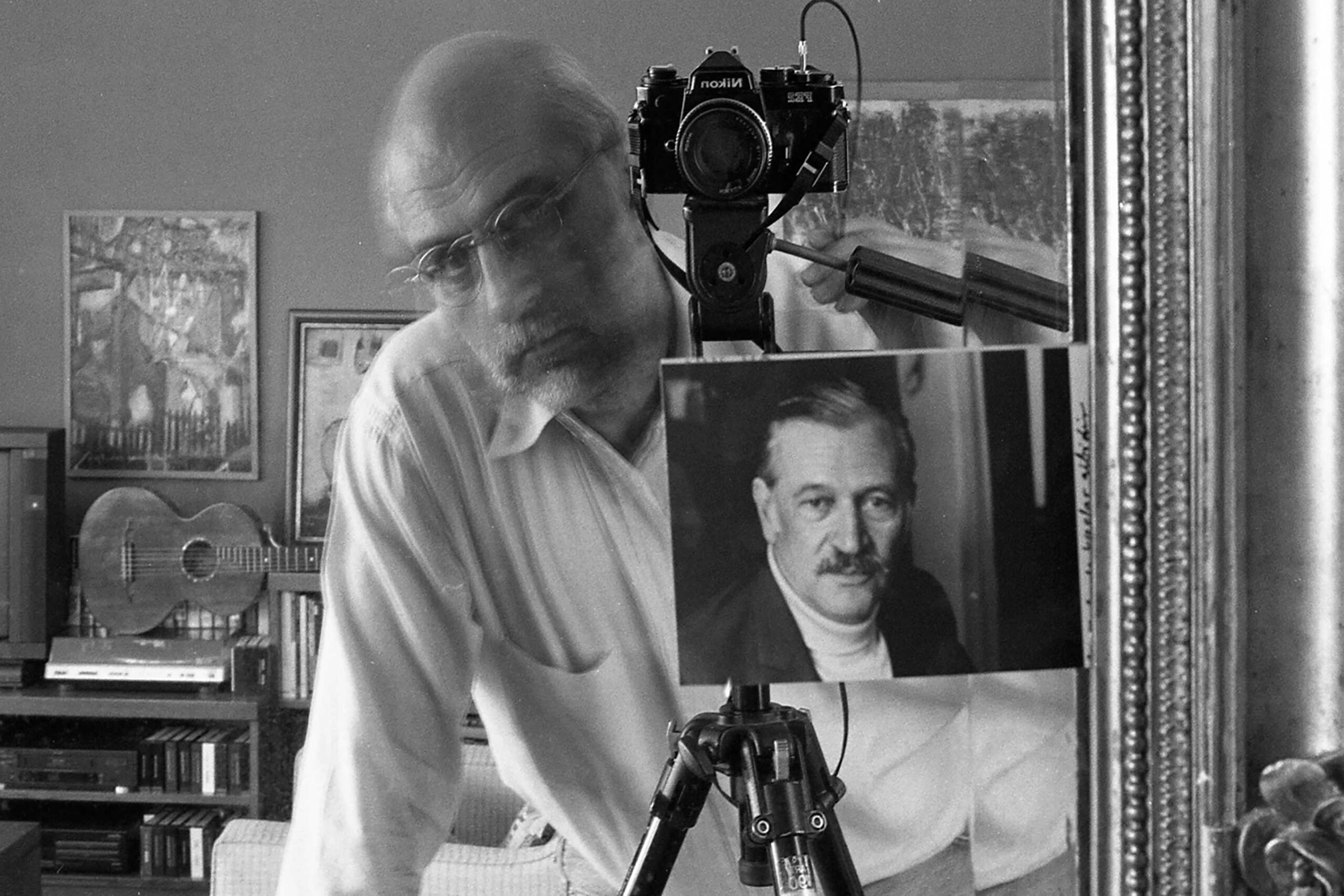

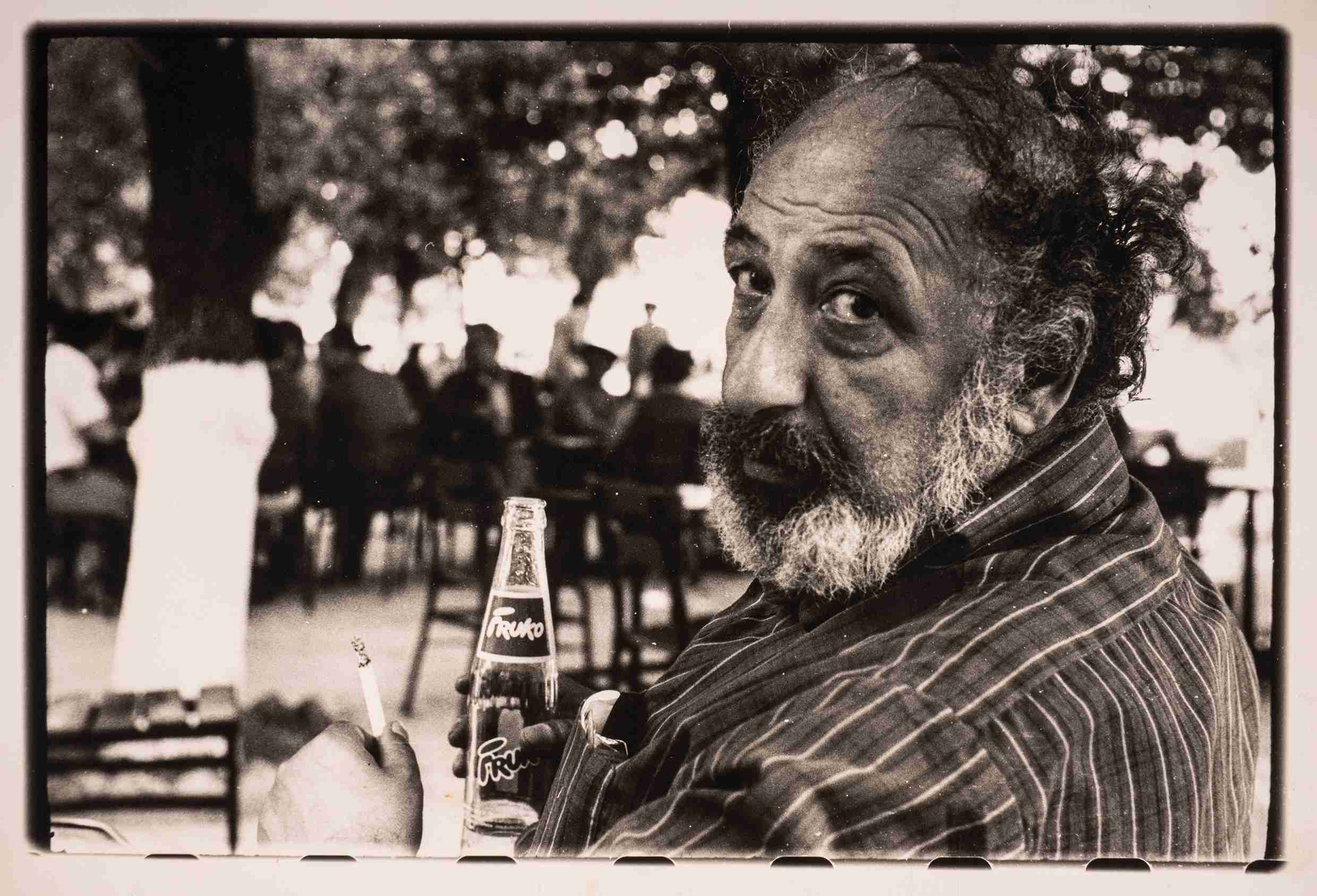

Rifat’s work in photography represents another major facet of his intellectual output. From the 1980s onward, his photographs accompanied his articles in various journals, reflecting his natural inclination towards visual expression. His book Between Black and White articulates his thoughts and perspectives on the art of photography. Esra Özdoğan evaluates Rifat’s relationship with photography as follows: “To read his photographs separately from his essays on photography, his poetic language and criticism, his translation work, and his architectural background would be to diminish his approach to visual imagery.” Although Rifat often referred to photography as a “craft” rather than a fine art, he readily admitted to infusing it with the shadow of poetry. As Özdoğan recounts, Rifat once wrote, “I have always believed that the art form closest to photography is not painting, as commonly assumed, but writing—and more precisely, poetry.” Finding pleasure in seeing himself as a colleague of street and wedding photographers, Rifat captured traces of memory stamped with the passage of time and mortality in his images. Time and death were critical themes in his photographic approach. As Özdoğan points out, “Samih Rifat often emphasized in his writings that the camera is simultaneously a time machine that summons death and revives the dead. Photography preserves memory, and the photographer, by pressing the shutter, creates the past in an instant.”

Rifat’s engagement with the history of thought materialized notably in his book Heraclitus: An Attempt to Encounter a Master of Obscure Sayings. This work is regarded as one of the most robust studies of Heraclitus in Turkish and represents a significant effort to bring ancient Greek philosophy into contemporary Turkish discourse. His contributions to intellectual history are evident not only through his translations but also through his original scholarly works like this.

One of Rifat’s most distinctive characteristics was his ability to integrate his diverse fields of interest into a coherent worldview. His pursuits in architecture, photography, translation, and intellectual history were all expressions of a modernist ethical and aesthetic vision. As Esra Özdoğan explains in her essay Samih Rifat: Before the Death of the Author, “He preferred the definite, the correct, the uncompromising, the universal, and the holistic over the ambiguous, the fragmented, and the relative.” According to Özdoğan, Rifat’s engagement across different disciplines did not fragment his identity but rather unified it, maintaining a consistent aesthetic and intellectual direction without compromise.

Samih Rifat, who passed away in Istanbul on August 4, 2007, left behind not just books, translations, and photographs but an enduring intellectual legacy in Turkish cultural life. His legacy goes beyond his individual works; it lies in his profound interdisciplinary knowledge and his ability to harmonize this knowledge into a comprehensive worldview. His advisory roles in cultural institutions, his curatorial work for exhibitions, and his meticulously selected translation projects are all products of this unified perspective. Evaluating Samih Rifat’s importance requires acknowledging not only his personal achievements but also his role in shaping the cultural policies and institutional visions that continue to influence Turkey’s arts scene. His efforts have undoubtedly contributed to raising Turkish cultural institutions to international standards. The exhibition Much Is to Be Done offers a comprehensive look into Samih Rifat’s intellectual journey. Rifat indeed had a lot left to do—and had he lived longer, one wonders what more he might have accomplished.

You can visit the exhibition “Much Is to Be Done” at the Pera Museum until August 17.