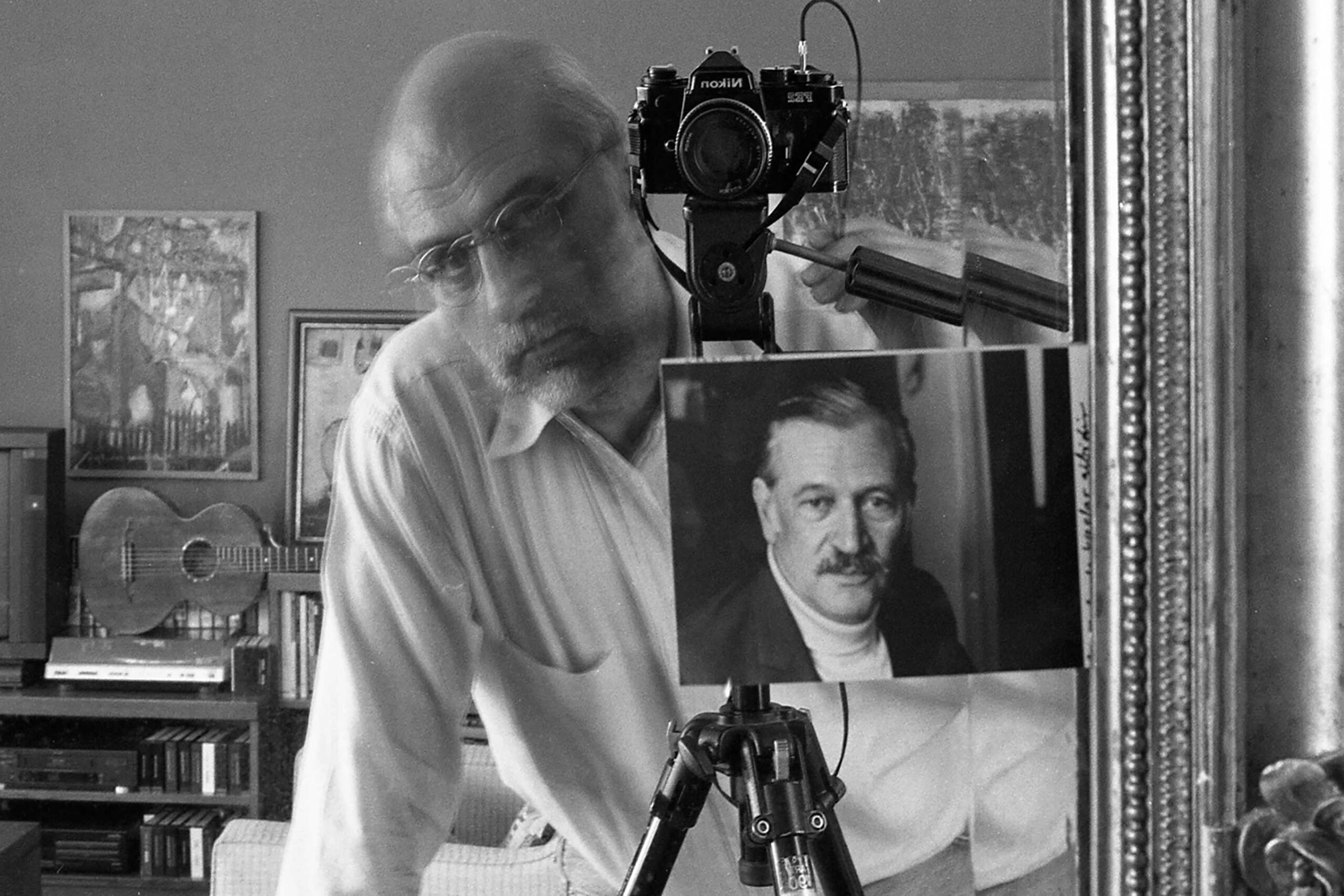

British choreographer James Sutherland took to the stage with Human, a piece he created for Ankara Modern Dance Company. We spoke with Sutherland, who said the work emerged from the question, “especially in this age of artificial intelligence, what defines us as human?”

Part of the Ankara State Opera and Ballet’s Ankara Modern Dance Company (Ankara MDT) program, Human was choreographed by British choreographer and dancer James Sutherland and premiered last month. Having previously worked on various projects in Turkey, Sutherland shared with us the creation process behind the piece and his thoughts on the current state of modern dance choreography.

How did your journey into dance and choreography begin?

It’s a very long story. I began many years ago with classical ballet at the London Festival Ballet, performing in productions choreographed by Rudolf Nureyev. To be honest, getting to where I am today was quite an adventurous journey. Even back then, I wasn’t particularly interested in classical ballet. I continued dancing with the National Ballet of Ireland, touring almost the entire world with them. Later, after moving to Basel, Switzerland, I had the chance to work with major choreographers like William Forsythe. Eventually, I decided that instead of being treated like a puppet, I wanted to create on my own, and so I started learning choreography.

What I truly desired was not simply to learn but to create. That inner urge led me to participate in a course designed for composers and choreographers, guided by Trisha Brown and the Judson Church movement, which had a tremendous impact on me. Since then, I have been working independently, and this path eventually led me to Turkey to collaborate on this choreography. I have been producing works through my own company, founded twenty years ago, and I consider myself lucky to live in Germany, where the demand for theater remains strong.

“İnsan Nedir?” Issue is Now Available!

Get it in both print and digital versions.

Click to see ArtDog Istanbul’s print magazine sales locations.

Turkish Edition

You premiered Human, which you choreographed for Ankara Modern Dance Company, on February 18. How did the idea for Human come about? Could you tell us its story?

The idea behind Human partially stemmed from a question that has always intrigued me: especially in today’s age of artificial intelligence, what truly makes us human? As I pondered this, I arrived at an answer focused on humanity’s potential to transcend its own physical limitations. Under certain conditions, when physical and spiritual strength combine, humans can access an extraordinary force. For example, a mother lifting an entire bus to save her trapped child. It raises questions like, “How is this possible?” and “Where does such strength come from?” leading to the realization that this capacity is what makes us truly human. This potential can take us to an entirely different plane filled with infinite possibilities—something artificial intelligence can neither achieve nor replicate. I was fascinated by this idea and started to imagine how I could express it through dance. That is how Human was born, and I believed it could become a powerful dance performance. I hope what you see on stage captures that spirit—choreography about surpassing limits.

In our conversation, you mentioned that this production created a unique moment of cultural exchange and transformation for both you and the dancers. I know this isn’t your first time working in Ankara. How was your creative process this time?

I would describe this piece as a co-creation. When creating work abroad, you inevitably encounter many challenges. After all, I have my own worldview, and you have yours. The question for me was how to merge these perspectives and communicate them effectively. Thus, a significant cultural shift had to occur for both the dancers and myself. Honestly, it wasn’t easy to come together and create a piece that carried real meaning. It was incredibly challenging and forced me to open my mind to many different aspects of life in Turkey. I believe the MDT dancers also opened their minds to understand my work, and I hope that’s true.

As we continued working together, extraordinary things began to happen. The final piece came together in just the last few days, and it wasn’t because I imposed my vision on them. In fact, the dance itself became stronger than either of us, taking control of the process. In the end, something remarkable occurred: they understood everything at once. It was an unforgettable experience for both them and me. People from different backgrounds and cultures truly merged into one. I suddenly felt like I was a part of them, and they were a part of me. It was a truly special experience.

Yes, I have worked in Turkey before. At that time, I created a piece for a classical ballet company. I had staged a work for Stuttgart Ballet, and the director of the classical ballet company in Ankara invited me to bring it to the stage there. I had a wonderful time working on that production. The work, titled Blue, was a 30-minute choreography set to music blending compositions by Bach and Brian Eno. As a choreographer, I believe it created a special moment for both the dancers and the audience, opening new doors. That was my first work in Turkey. Later, the pandemic interrupted everything. During that time, Ankara MDT reached out to me for their 30th-anniversary celebrations. They invited me to choreograph O Superman, based on Laurie Anderson’s music, which offers a satirical look at toxic relationships.

After that, MDT’s director Bürge Kayacan invited me back to Ankara. This time, rather than re-staging an older work, I wanted to create something entirely new. I saw it as an opportunity for both myself and the dancers to embark on an adventure. I didn’t expect it to be quite so adventurous, but in the end, it was a wonderful experience, and I am very happy we took that path. I hope MDT is also pleased with the result.

This project involved an almost entirely new way of working for me. When we began, there was no music yet. Typically, Davidson Jaconello, a very busy composer, arrived in Ankara and started developing the music on-site. Nothing had been composed beforehand. We had to make certain decisions early on and realized that we should use the music that surrounded us. So, we selected some old, traditional Turkish pieces, blending them beautifully with electronic sounds. This created a foundation that gave the music a depth aligning closely with the themes we were exploring. The first half of the performance focuses on the diversity of human existence and physicality, while the second half shifts toward the spiritual dimension. The choreography concludes with a collision of these forces, set to Bolero. This was a theme Davidson closely followed, and Bolero became a symbol of human beings synchronizing physically and spiritually across space and time.

We literally built the music day by day. Sometimes during rehearsals, I would test a section, and he would observe. Gradually, we crafted the musical foundation from scratch. I found this approach very harmonious with the creation process of the dance because what you hear shapes what you see and vice versa, allowing the dance to unfold in two distinct parts. Thus, music and sound became an inseparable part of the choreography.

Dance and choreography today seem to have evolved into more interdisciplinary and collective creative practices, involving contributions from other fields. Do you agree, and how do you think this affects audiences?

First, we need to define what choreography is. In the 1960s, figures like John Cage in music and Judson Church in dance redefined the very foundations of their disciplines. These pioneers radically reshaped contemporary dance, and the concept of choreography itself has been turned upside down. Choreographers are no longer simply instructors showing dancers steps; artists like William Forsythe and Ohad Naharin represent this shift.

Today, we work together, collectively. Of course, ideas and steps are still important, but the choreographer is no longer the sole creator. Dancers are deeply involved. There’s a major misunderstanding that improvisation equals choreography, but that’s not the case. It’s about how far the dancers can push themselves and how much the choreographer can guide them forward. Nowadays, the choreographer observes and decides what works and what doesn’t rather than demonstrating steps. This approach is perhaps the only way to create coherent, holistic works today.

I believe this radical change will continue. Choreographers might begin with one idea and then branch off in many directions, as we see with remarkable artists like Peeping Tom and Dimitris Papaioannou, who rethink even the stage itself. The choreographer ultimately becomes the director, free to use any component needed in the creative process. Everything depends on one’s perspective and what one wishes to express. Compared to other performing arts, dance seems to be advancing the fastest.

As for how this impacts audiences, I believe it transforms how they experience performances. Instead of watching something repeated hundreds of times, audiences are now invited into a shared, immediate experience. The fact that theater happens “in the moment” and that audiences are there to live it with the performers is a rare and powerful thing. Many artists today are exploring ways to capture this immediacy. It’s a broad framework and makes things harder, but there are still extraordinary talents in the field of contemporary dance who manage to achieve brilliance.

Do you believe that the rise of new media technologies, especially the rapid growth of social media, has helped deepen our understanding of the body and collective creation in performing arts? Or has it complicated things even further? From what I understand, you see these technologies as supportive forces?

That’s a fascinating question. Of course, new media technologies have evolved incredibly. However, if you look at it long-term, they have also harmed theater. At one point, theater represented nearly 100% of entertainment culture. Today, it accounts for perhaps only 5%. This means we must redefine what theater is and what it should create. I firmly believe that theater remains crucial as a platform for cultural exchange and for opening new perspectives on the world we live in. Theater is still the place where this happens—social media is not. On social media, you choose what you want to see; in theater, you cannot. Theater confronts you with questions and offers different ways of seeing the world. It opens the door to cultural understanding and touches the very foundation of what it means to be human.