Why did you choose to research this exact period?

Daniel-Joseph MacArthur-Seal & Gizem Tongo: The final decade of the Ottoman Empire up to and including the occupation is a period that we both have worked on academically since the start of our doctoral studies. While the period is well known in Turkey, the focus of public memory and history writing has been the struggle for independence in Anatolia, leaving the city of İstanbul out of the spotlight.

Why do you think this period is essential for the city?

DJMS & GT: Istanbul was the only capital city to be occupied as a result of the armistices that brought the First World War to an end, and the only capital whose future sovereignty was put into question. Whether the city would remain part of the Ottoman Empire or be handed to Russia or Greece, come under international government, or be mandated to one of the victorious imperial powers was debated for almost five years. This international political contestation was reflected in social and cultural life, which was marked by not only the weight of military occupation but also by divergent influences and diverse encounters between locals and outsiders.

How long did the research take? Which parts were the hardest?

DJMS & GT: We have both been working on this period for some ten years. This familiarity allowed us to identify and gather the materials for display in a relatively short period of time; around nine months between our appointment as curators and the exhibition’s launch in January 2023. Because of the many international interests in the city during this time, the period is among the best documented in Istanbul’s history. As such, it was challenging to choose which of these rich materials to include in the exhibition space, while still reflecting the complexity of political, social, and cultural life at the time.

This period is full of traumas and transformations. How did the city change afterward? What are your reflections as an academic and researcher?

DJMS & GT: Among the most dramatic changes to the city following the occupation was its demographic decline. Between the final year of the occupation and the foundation of the Republic of Turkey, tens of thousands of local Greek and Armenian Christians left the city, as well as smaller numbers of long-resident Europeans and most of the Russian refugees. After 1923, Istanbul was no longer the capital and suffered a loss in economic activity and population as well as prestige and status in the early years of the Republic. Despite this and subsequent waves of exile, the departing population left a substantial cultural legacy, still visible in the built environment of today’s rapidly expanding mega-city. As academics, we felt it was important to communicate to visitors the character of urban life prior to these major changes and to highlight some of the period’s similarities with our present time, such as high inflation, housing issues, and immigration.

How did this period shape city life?

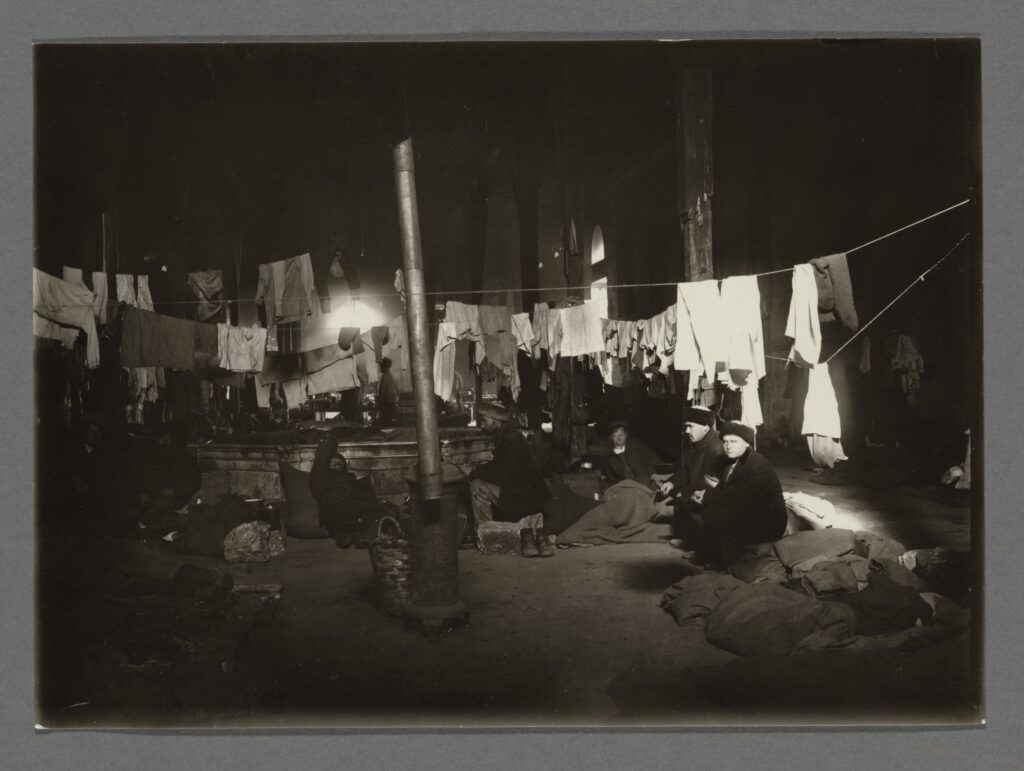

DJMS & GT: The occupation had a wide-ranging impact that was felt by all quarters of the Istanbul population. The presence of British, French, Italian, Greek, and African and Asian colonial soldiers as well as refugees from Thrace, Anatolia, and especially Russia was inescapable, with numerous buildings converted for their accommodation, while army cars sped down city streets. The city was rocked by large demonstrations against Allied policies and strikes for better pay and conditions as living costs skyrocketed. Day-to-day business could be interrupted by parades of Allied troops, searches for arms and contraband, or the imposition of curfews and other security measures. Art exhibitions and musical and theatrical performances, including new genres like Jazz, were advertised for the city’s growing resident and non-resident audiences, contributing to a lively nightlife that many residents found immoral and disturbing.

Can we say this period was also a flourishing time for the press and literary arts?

DJMS & GT: The lifting of the strict censorship regime imposed by the Committee of Union and Progress during the First World War led to a boom in publishing, with new newspapers appearing in multiple local and foreign languages. While political topics, especially the developing nationalist movement in Anatolia, were censored by Ottoman and Allied officials, the discussion of science, sport, literature, and arts remained relatively free, reflected in the large number of multilingual journals published in the period. Suspicion towards the İstanbul press in the years following 1923 saw the closure of several important newspapers, such as Tanin, Tasvir-i Efkar and İleri.