This week’s guest in our ‘Independent Artists’ interview series is Leyla Emadi. We discussed the relationship between independence and freedom, the evolution of contemporary art, and the impact of external pressures on artistic expression.

While being an independent artist comes with its challenges, in our previous interviews, it has often been associated with creative freedom. What are your thoughts on this? How has your journey unfolded?

In my view, freedom in art or artistic production is about maintaining one’s existential struggle despite different eras, individuals, institutions, and political powers. However, within this capitalist system, my dream of *free art/free artist* often feels overly idealistic. Therefore, discussions about independent artists, artistic freedom, or how free art truly is can only be framed within this broader context.

Every form of freedom comes with its own costs. Unfortunately, in the art market, everyone is inevitably linked—like links in a chain—to these costs. Whether an independent artist, an art dealer, a gallery-affiliated artist, a gallerist, or even institutions and banks, in the end, everyone is accountable to someone. I don’t say this in a strictly hierarchical sense, but if we look at it through the lens of supply and demand, political positioning, and economics, these dependencies become quite evident.

Under these circumstances, the concept of an independent artist becomes somewhat ironic. However, compared to an artist represented by a gallery, there is relatively more freedom in production, exhibition choices, venue selection, and even sales. Yet, this freedom comes with a heavy burden that always lingers alongside it.

An independent artist must find exhibition spaces or galleries, handle promotional efforts, organize invitations, cover printing costs, and, if a sale occurs, navigate financial negotiations—which, in my opinion, is one of the most challenging aspects for an artist. Additionally, they must thoroughly research potential buyers. The list of responsibilities grows longer, making independence both a privilege and a challenge.

If I turn to my own process, I have experienced all the issues I mentioned above over the years through my friends and my own lived experiences. I have been working as an independent artist for as long as I can remember. Since graduating from school, which has been 21 years now, I’ve never had gallery representation. Of course, I’ve occasionally had joint and solo exhibitions with some galleries, and during those times, I’ve sometimes felt that the ease with which things can be resolved in a gallery with an established system made the idea of being a gallery-represented artist seem not so bad. But at the end of the day, when I weigh everything, I’ve realized that staying true to myself feels better.

“I Could Only Exist Within a Structure That Is Emotionally, Mentally, and Ideologically Aligned with Me”

I can’t say for certain that this will continue as such in the future, but as I grow older, my individuality comes more to the forefront. Therefore, if I were ever to enter into gallery representation, I would think that I could only exist in a structure that is emotionally, mentally, and ideologically aligned with me before anything else in my artistic production.

Galleries work with specific collectors’ portfolios and art dealers based on the size and history of the gallery. Do you think the choices of the audience who consume art have an impact on the artist’s production or the gallery’s choice of artist?

I could answer this question with both yes and no. In fact, the answer is connected to the issues I’ve discussed above, but if we look at it in terms of shaping or being shaped, it can be observed from three different perspectives. It is more likely for a gallery or a collector to shape an emerging artist, especially a candidate just starting their art career. The artist often doesn’t see a problem with this either, as they are struggling to exist and seeking visibility. In this direction, they may shift their production based on the gallery’s or art buyer’s choices. However, for an artist who has reached maturity or has established a strong brand, I don’t think this is very possible.

“Sometimes, the Artist Might Fall into the Jungle of ‘Custom-Made Work’—a Pitfall We Should Avoid!”

Galleries already work with artists whose views align with their own and their clientele’s, so I don’t think there’s a possibility of a radical change being imposed on the artist’s production. At this point, I’d like to think of the gallery as one that protects and supports its artists. Of course, sometimes artists might fall into the trap of “custom-made work,” but that’s a whole separate pitfall we should definitely avoid… The third scenario is that when galleries or art dealers choose new artists to represent, as you said, they tend to align with the preferences and demands of the audience, the “buyers,” who are consuming the art.

Although there may not be any statistics on this topic, based on observation, we can say that collectors tend to lean more towards works on canvas or paper, rather than mediums like installation or video. Galleries, especially at art fairs, showcase works that align with the preferences of collectors—or perhaps, the galleries’ selection influences the preferences of collectors. As an artist who works in many of these mediums, what do you think is the reason for this?

“I Think This Trend Has Changed in Recent Years”

I actually believe that this situation has changed in recent years. In the past decade, even in our country, I know that there has been a significant increase in the acquisition of video, digital art, and installation works. Of course, these works are not as easy to display in every home as canvas or paper pieces, but I think this is due to the fact that the dominant art understanding still comes from works made with canvas, paint, paper, and pencil, which have entered historical museums and become subjects of books.

As art perception and literacy evolve, and as we progress in understanding, perceiving, and digesting contemporary art, it will become more commonplace to acknowledge that there is a world of art beyond just canvas paintings or paper works. In fact, nowadays, some collectors and museums are only collecting works by artists who produce video or installation pieces. I think this kind of distinction in collecting is a brilliant approach. On the other hand, within a gallery or the limited space of an art fair, installing an artwork can be spatially, logistically, and financially challenging. This is true for collectors as well, because while placing and preserving a framed painting, a small sculpture, or a canvas is more feasible, exhibiting an installation or video requires significant effort and sacrifice. Therefore, whether the installations at art fairs are determined by the collector’s preferences or if galleries are imposing their choices on the collectors, the answer is “all of the above” based on these conditions.

You have lived and observed two regions where pressure is visible in all aspects of life. What do you think about how art takes shape under pressure, the tools of pressure, and the creative approaches artists develop in response to this?

The word “pressure” may have a negative connotation, but I would define it as a “drive” that allows us to challenge our limits, find new ways of expression, see other windows we hadn’t noticed before, and reach the light within the darkness.

“Despite All the Pressure, I See Exhibiting One’s Art as a Form of Resistance”

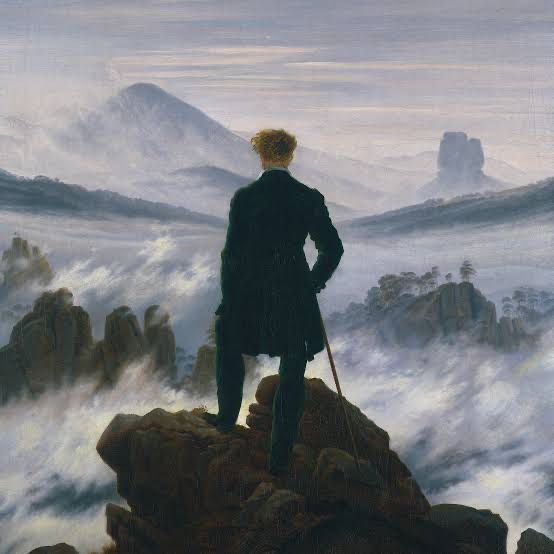

Yes, being under pressure doesn’t feel good at the moment; it restricts one’s freedom, but it has an anarchistic side that triggers a shift to another version of oneself. For that reason, despite all the pressure, I always see presenting one’s art as a form of resistance. This resistance could be psychological or sociological; it doesn’t matter—it requires an outward expression from the artist either way.

If I speak of Iran, since 1979, hundreds of artists, filmmakers, writers, and illustrators who have been subjected to constant pressure and oppression have somehow managed to make their voices heard. Even though messages couldn’t be directly delivered, over the years, they have managed to establish themselves through creative forms. They fought censorship and oppression with symbols woven into carpets, metaphorical or ironic images placed in their paintings, and poetic language in their films. This struggle continues today.

“If We Use Negativity or Pressure as a Catalyst, We Fulfill Nazım’s Line: ‘To Live Is to Resist'”

Of course, for me, being caught between these two countries was very challenging for a long time. Trying to deal with pressure often felt as futile as Sisyphus’ effort to roll the boulder up the hill. Over the years, through returning to myself and my past, I realized that I should focus on the positive aspects of this pressure, the richness it brought and could bring to my life. Because I believe that staying in a negative emotional state makes a person numb; on the contrary, if we use negativity or pressure as a catalyst, we truly fulfill Nazım’s line “To live is to resist.”

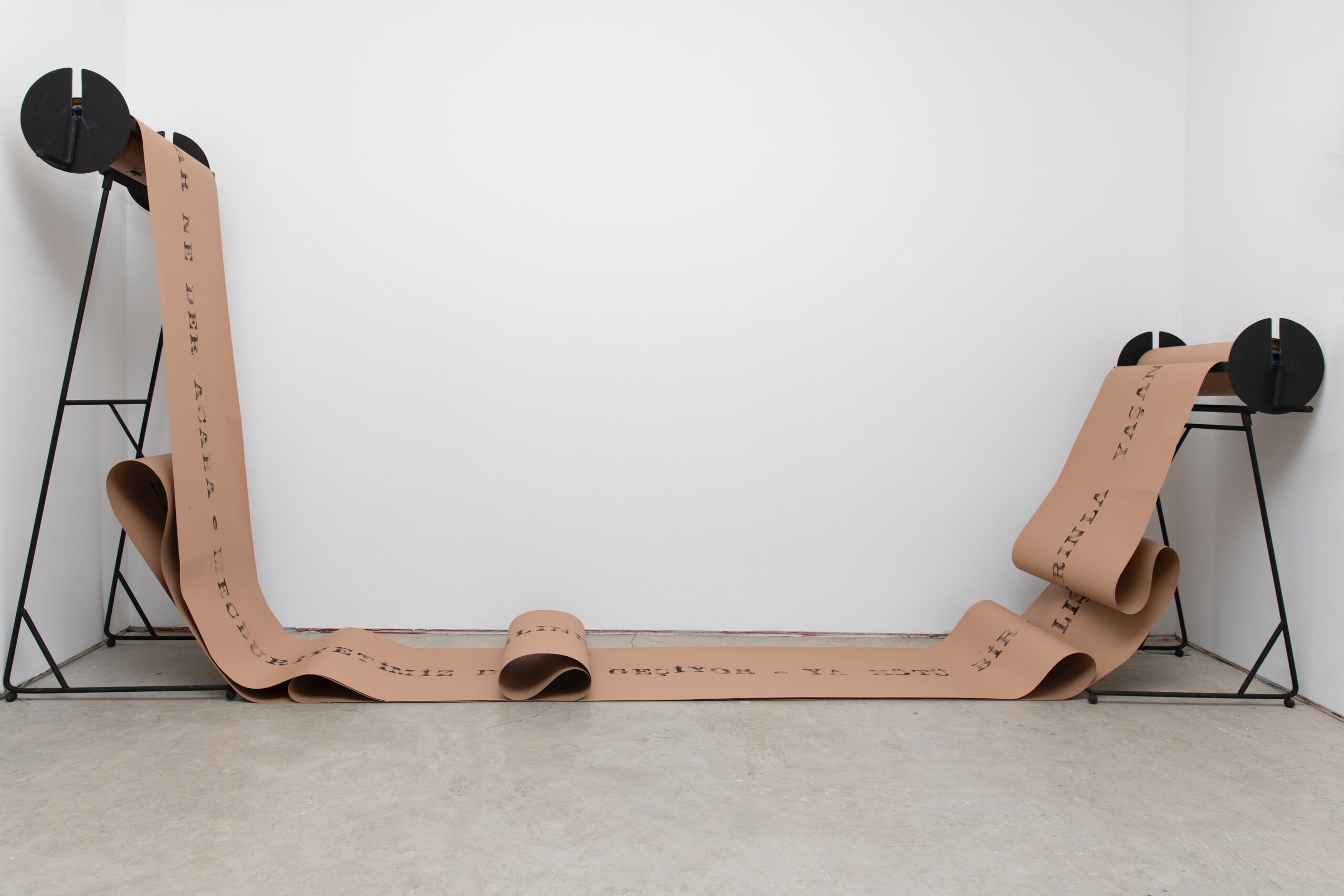

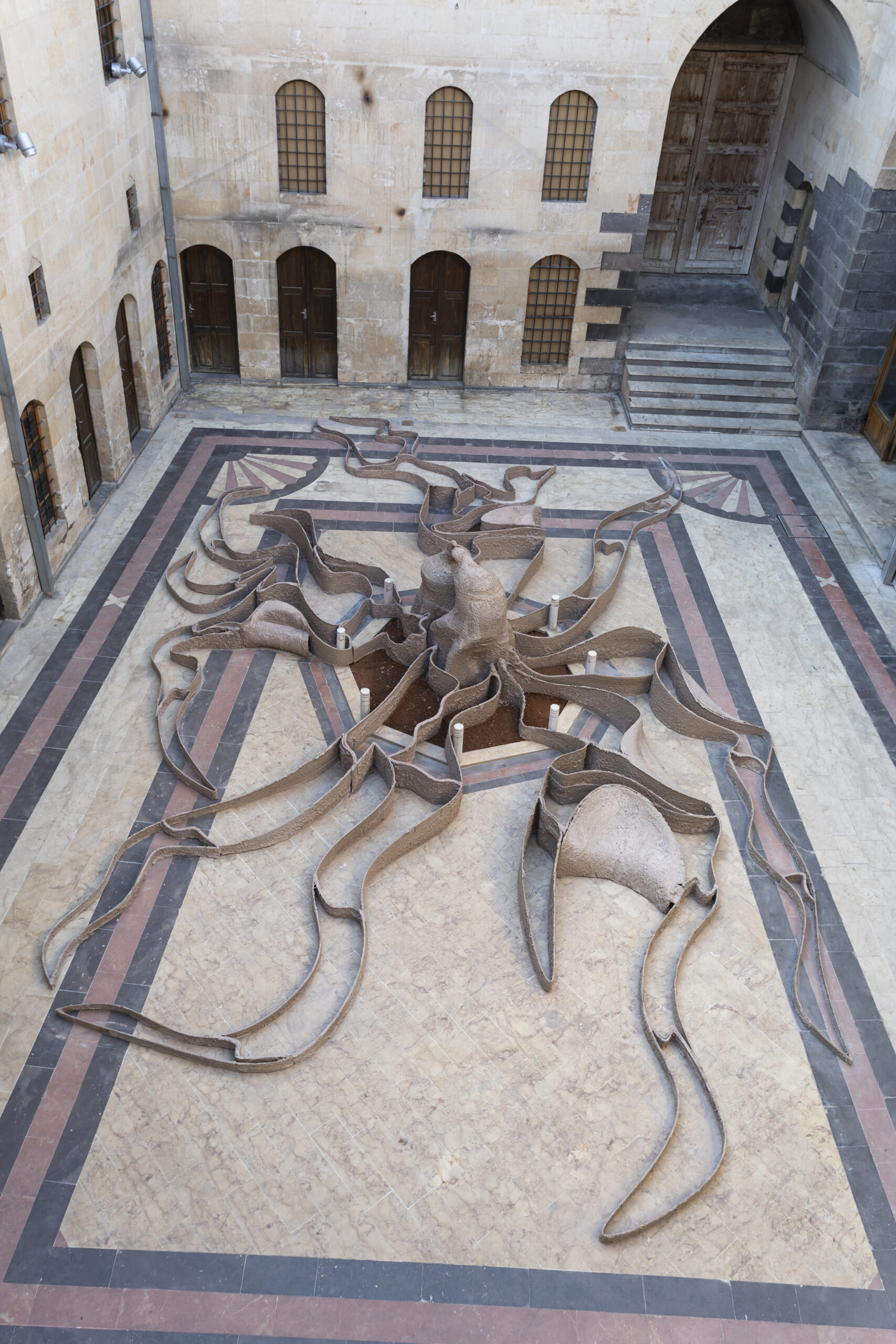

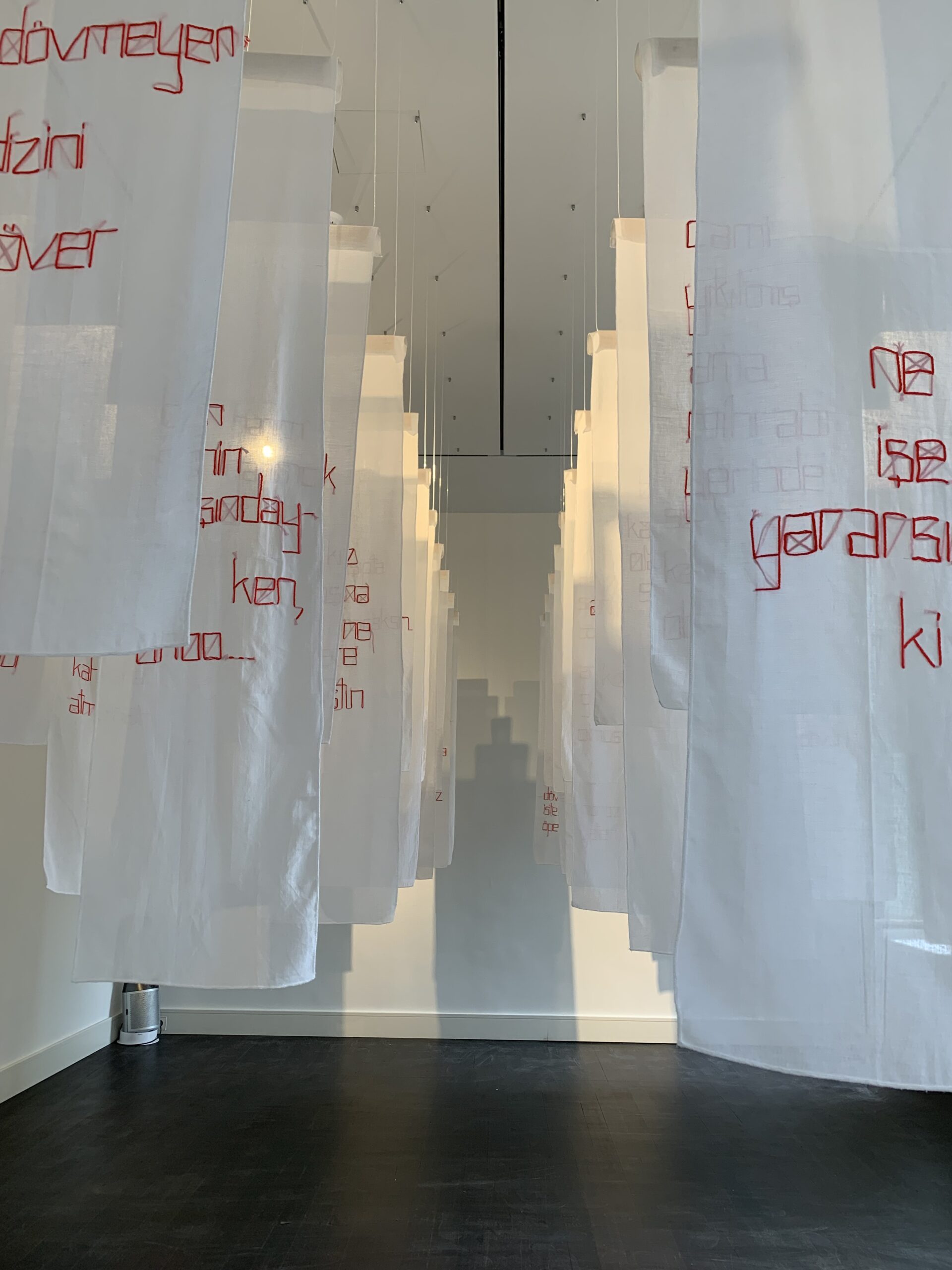

Leyla Emadi (b. 1977, Ankara) began her artistic journey in 1995 at Los Angeles Pierce College with 3D Art, later continuing at Yeditepe University’s Faculty of Fine Arts, Department of Painting. After completing her master’s thesis titled *”Material Use in Art and Paintings with a Door Theme”* at the same university in 2006, she continued working in her own studio. She is currently working on her thesis *”Character Structures and the Effects of Trauma on Artistic Individuals”* in the university’s Art Proficiency program.

The artist has participated in numerous exhibitions and fairs both in Turkey and abroad. Her works address the psychological and sociological underpinnings of trauma, examining the individual’s connections to gender, religion, politics, ideology, and ingrained thoughts.