Jonathas de Andrade’s work O Peixe at old Antrepo, now Resim Heykel Museum, has virtually become the symbol of this year’s Istanbul Biennial. If the organizers at IKSV did a survey of all the works, it could have been chosen as the most outspoken and compelling work of the exhibition.

When Milo Conroy came to Kiraathane Istanbul Edebiyat Evi with Jared Madere to give a panel talk, he said that Ozan Atalan’s work titled Monochrome (I call it the ”buffalo”, as it frames a buffalo skeleton), was his favorite photography/video work.

Of course I went out of curiosity. I had already visited the Pera Museum and saw the works at Büyükada and I thought to myself ‘‘oh god’’. The Biennial had somewhat disappointed me. But, after spending three tiring hours in the endless floors and corridors of Antrepo, my opinion somewhat changed.

I’m going to tell my story through some detours along the way.

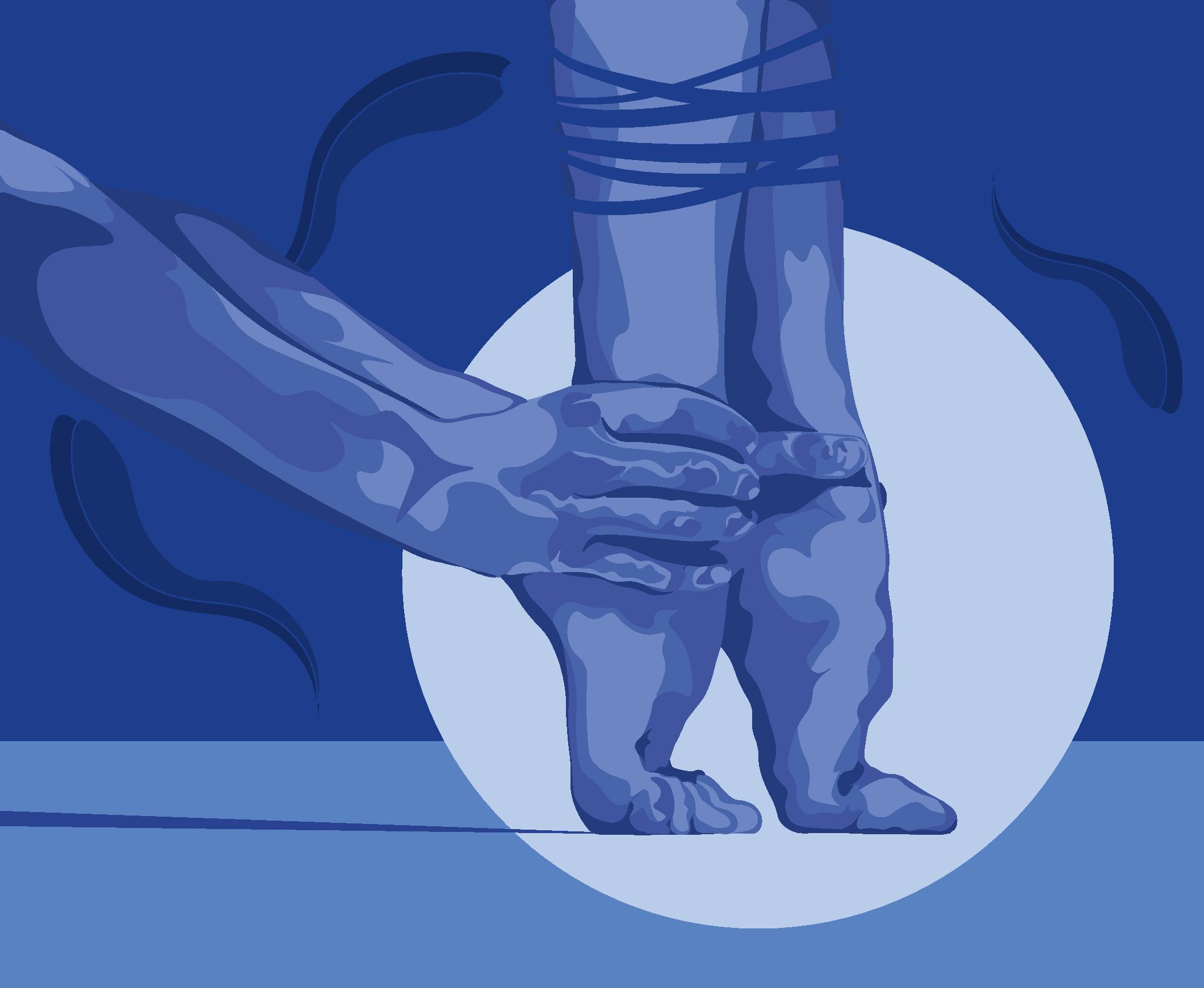

The local Brazilian fishermen that de Andrade shot, held the fish close to their chests, hugging, stroking and pressing their cheeks against them so as to show their pity, to apologize and ease their death. Of course the fish still flutter, struggling to breathe and live. They don’t care about compassion. It’s not an easy job holding a fish in one’s arms either.

What is this act of killing with compassion? Is it a way of paying respect to nature, a thank you or an apology? My mind was filled with questions: Are we modern humans currently killing nature with compassion or are we trying to go on a killing spree? Is there a difference between the two? Even if we kill with compassion or go on a killing spree, aren’t we causing too many problems for nature? Isn’t the climate crisis a warning of this? Is not eating meat enough? Does going vegan serve anything? Is it possible to stop producing plastic?

The current topic of the Biennial revolves around the same questions. The ‘‘Seventh Continent’’ on the Pacific Ocean is like a new continent, composed of plastic waste and garbage. In short, we are at a biennial about the climate crisis.

I leave de Andrade’s video and go one floor down to see ‘‘Feral Atlas Collective’’s works. The Collective, made up of scientists and artists, document how human-made technological and industrial infrastructures damage the environment through the ‘‘Yabanıl Atlas’’ project. The Guardian columnist Adrian Searle’s saying, ’‘It’s impossible not to panick’’ is spot on. Hearing the noise pollution that we cause under the sea is especially mind-boggling.

Walking in that large room in horror, among the animal and plant holograms, dirt volcano images and documents of destruction, I came across a video, Chris Jordan’s Albatross film. When he went to the Midway Islands on the Pacific, cruising the edges of the Seventh Continent, he came across an albatross cub and recorded its rotting corpse, its stomach full of plastic bottle caps, lighters and some other plastic garbage.

The interesting thing is the almost spectacular beauty of the untouched footage of this decomposing corpse. Nature has such beauty that even things perishing creates esthetic images. We’re getting carried away by this unavoidable esthetic of disappearance and destruction.

Showing the garbage produced as a result of our consumerist habits, Jordan named some of his works Unacceptable Beauty. The labyrinth-like demolition process yields unexpected beauties pulling us deeper into the darkness of un-sustainability. Jordan calls this process the ‘‘Slow Doomsday’’ and claims that these images are like a mirror held up against humanity. I couldn’t agree more.

I should say that I’m on the pessimistic end. I think to myself ‘‘Let’s say we don’t use plastic, what difference does it make when the production of it doesn’t stop?’’. Of course, Chris Jordan is aware of this and he says that as an American consumer he doesn’t have the right to lecture anyone. But at the same time, he touches a sensitive point: we are irreversibly destroying the universe as much as we are damaging our souls. Obviously, there aren’t any easy answers to this problem. Nevertheless, the artist shows that when we turn our attention inwards and focus on our emotions, we could gain some insight, take action and find the opportunity to evolve. Indeed some of the audience quit using plastic after seeing the artists’s dead albatross cub.

The Albatross movie, along with the text voiced by the artist and the music in the background, is also quite moving. I have watched the film over and over again and at some point I noticed that I started to cry.

Reading the text describing Jordan’s sorrow, I realized that I share the same feelings with him: ‘‘In this experience the true nature of sorrow came out. I saw that sorrow is not the same as sadness or hopelessness. Sorrow is like love. Sorrow resembles the love we feel towards something that is slipping away or something that we have already lost.’’

The images of environmental catastrophes reveal the hidden aspects of our culture. I suppose this year’s Istanbul Biennial is creating moments of enthusiasm and awareness in this grief we feel due to the fact that we are losing the earth. So, it takes us to the base of a very current and urgent problem.

Touring the Biennial, I have come across many works that gave me the impression of being weak or irrelevant. I got the feeling that the messy installation was barely finding its ground. However, in my mind, the compelling works, which evoke emotions and leave an impression, somewhat balanced the shortcomings of the other works.

The climate crisis, environmental and man-made destruction stemming from capitalism and the attempts to heal the universe and ourselves has turned the Biennial into an extensive encyclopedic study. But in the end, we’re talking about a mess that is a bit too much for humans.

The curator Nicolas Bourriaud wasn’t particularly lucky. When they found out that the large exhibition space at Haliç Tersanesi contained asbestos, the Biennial had to be moved to the Resim Heykel Museum (Istanbul Museum of Painting and Sculpture) in short notice. The change of the exhibition space ironically points to the environmental issues of Istanbul, but the sterile, sectionalized rooms of the characterless building that replaced the old Antrepo didn’t really serve the exhibition. Touring the exhibition, one feels isolated.

The frailty of the exhibition lies in the contradictory narrative and staging strategies. It brings a complex set of things together: from encyclopedic or collective case studies, entertaining or mocking critical statements, constructed imaginary worlds, futuristic ‘‘post-human’’ depictions, shamanic healing suggestions to political activism methods. If it weren’t for certain breathtaking works, it’s hard to see this Biennial.

Of course it is possible to view this diversity as richness, but making climate crisis the theme is another issue. ‘‘Anthropocene’’ has become a trending word lately, referring to the Anthropocentric culture that is dominating and threatening nature more and more. We come across this word quite often at the Biennial, although it is not obvious how this word could be misleading, how could we move on to a less human-centric perspective and what does it mean to move beyond the human-culture duality.

There was another proposition which excited me at first and gave me hope, however then I realized I lost my track. There were times where I felt like the Biennial was about to shed light on how we could overcome the dualities of our time; me-other, nature-culture, art-world, inside-outside, but in the end I got side-tracked in the mess.

Of course there are some exceptions like there are at any other large scale exhibitions.

Ozan Atalan beautifully captured the buffalos wandering around in mud aimlessly who lost their living space to a construction project in Istanbul. The buffalo skeleton laid in the middle of the room is a dramatic reminder of this forced displacement. This work lifted the indifference we feel towards other species and the distinction of me and the other for a moment. Moments of desperation reappeared in my mind, making me think that I’m sharing a similar faith with other animals. Perhaps, I imagined a more mindful approach to the Anthropocene concept for a second.

If there were more illuminating and esthetically simple works, the Biennial could have left a greater impression on me. In this sense, Deniz Aktaş’s work, conceived with great simplicity, depicts waste car tires so delicately.

On the contrary, Simon Fujiwara’s installations create a fair-like environment. We are at an entertainment tunnel with dystopian fictionalized architectural sites, like hospitals and prisons decorated with the puppets of Bart Simpson and Joker as well as the Pop icon figures. Perhaps mocking the deadly deceptions of capitalism; the dairy farm and the gymnasium are placed parallel to each other, with a series of cows connected to milking machines and a series of sportsmen stuck on treadmills, lined up side by side, with tiny figures, flashing lights and “functioning”. The name of the work is called, “World is too Small” and it’s true. It’s getting smaller and smaller every day. The message and the joke is good, but creating a huge mess for such a small irony weakens the experience that the artist trying to elicit.

The Pera Museum section of the Biennial confused me even more. I thought to myself would the exhibition lack anything if this section didn’t exist at all. Futuristic worlds, archeological fantasies perhaps destroy the ‘‘Anthropocene’’, that is to say human-centric domination. I saw works that made me feel like I was a creature put under a microscope, it’s all good, but this feeling of being crushed didn’t lead me anywhere. I am also tired and bored of curators’ obsession with presenting historical and contemporary works side by side. I don’t want an art history lesson, I’m after a qualitative experience, investigation and transformation.

The Prince’s Island was especially problematic for me.

It was nice watching Glenn Ligon’s work, documented by Sedat Pakay, showing James Baldwin in Istanbul. Although I’m not sure if it was worth spending three hours on the road. Monster Chetwynd created cute monsters, true to her name, and it was fun seeing these human-animal hybrid creatures, but sadly it left no impression on me. At least the permanent game space with the Gorgon heads that the artist made at Maçka Park is a contribution to Istanbul. I guess the strength of the exhibition lies in the fact that there were many works made specifically for Istanbul. Out of 55 artists, 36 contributed to the Biennial with new works.

There were two works that impressed me at the Prince’s Islands.

Firstly, Armin Linke’s incredible video work which documents how the ocean is damaged to extract mines and make profit. What makes this work interesting is that the artist touched on local issues: the flow of the Bosphorus was first calculated by the Italian scientists Luigi Ferdinando Marsili from Bologna in the 17th century. Marsili also sketched all the sea creatures of Istanbul spectacularly. Realized with the contribution of Emin Özsoy from İTÜ, this work is worth being exhibited on its own. I know I said I don’t want an art history class, but this class was a big revelation for me.

The work of Hale Tenger at the neglected garden of the old Taş Mektep ruin in Büyükada was also attention-grabbing. She planted the obsidian stones used by old people as mirrors, like standing space antennas and suggested that we take a good look at ourselves through the mirror of nature. Similarly, Chris Jordan said that the sound installation channels the inner voice of a tree and provides an impressive balance between creation and destruction.

I had a chance to look at the GalataPort construction site while visiting the Resim Heykel Museum (Istanbul Painting and Sculpture Museum). It is evident that we are drowning along with traffic, plastic, concrete ruins and human rights. Dora Budor’s work titled Origin made from dust and pigments in glass boxes vibrate due to the noise of the GalataPort construction. This is a masterpiece that pays homage to the fragility of art and humanity and raises important questions: could we approach the climate crisis from an esthetic viewpoint or are we at an esthetic age of destruction, extinction, decadence?

The image that left a mark on me is still the albatross. The elegant large wings of a glider on the Pacific, the corpse of the cub with its stomach filled with plastic on the beach. I remembered Baudelaire’s Albatross poem, I imagine humans soaring with art and at the same time we are crawling in waste; while my heart is still searching for the meaning of killing fish with compassion. Perhaps this feeling, this search, despite everything, could be seen as the success of the Istanbul Biennial.