In the exhibition “Pánta Rheî / Works 2021–2025,” Elvan Alpay’s works possess the quality of being an experimental field left to the material’s own flow, beyond being a fixed image. We spoke with the artist and the exhibition’s curator Levent Yılmaz about the exhibition’s setup, the relation of Alpay’s works with nature, and how things “take place.” The exhibition, continuing until January 3, is at Sevil Dolmacı Gallery’s Villa İpranosyan building.

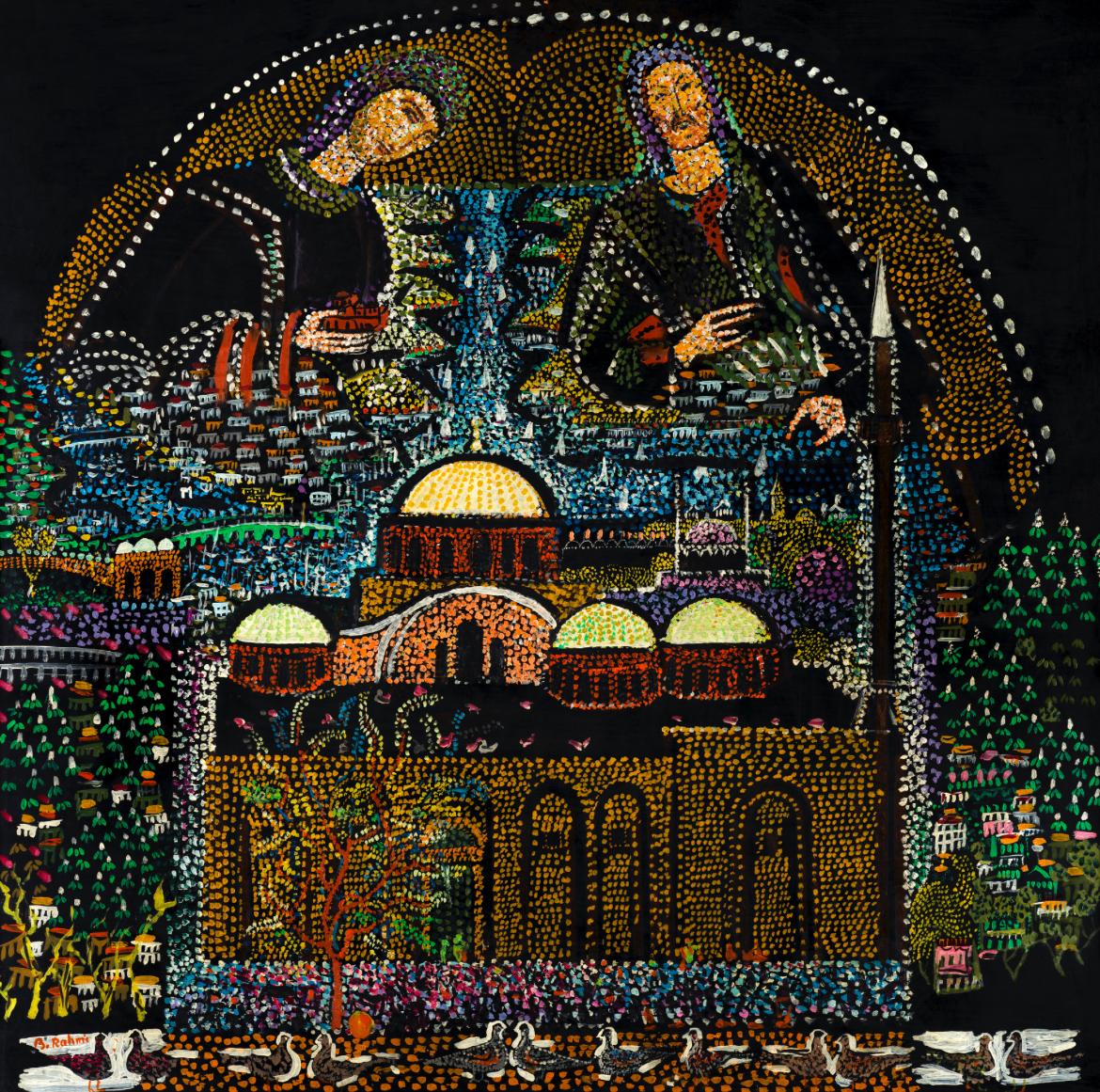

Elvan Alpay’s Pánta Rheî / Works 2021–2025 exhibition brings together the works the artist has produced in the last five years, while inviting one to think not as a completed picture but as a “happening” state of becoming. Pigment, glass powder, acrylic, and light cease to be merely materials on the artist’s canvases and transform into parts of a physical event. The exhibition, curated by Levent Yılmaz through the understanding of nature by Heraclitus, leaves the viewer not with fixed meanings but with the rhythm of uncertainty, transformation, and emergence.

We spoke with Elvan Alpay and Levent Yılmaz about the technique of Alpay’s works standing between sculpture and painting, their relation to nature, and the exhibition’s setup.

The works in the exhibition may be in the form of a painting, but their feeling is close to sculpture, almost creating a three-dimensional effect. In this sense, could you speak a little about your technique?

Elvan Alpay: I think it would not be an exaggeration to say that most of my works stand between painting and sculpture. My exhibition “Tales for Adults,” which I opened in 1993, consisted of giant bananas, cherries, and grapes on which colorful toy frogs were placed. Afterwards, I made aluminum and mirror castings; I used materials such as glass and stainless steel, epoxy, plaster, wood paste, and many different materials to give dimension to the canvas surface. My basic working practice of multiplication and assemblage evolved through many different materials over the years. My 2013 exhibition Biophilia is the only exhibition in which I remember the canvas ground being calm and one-dimensional.

In this exhibition specifically, I experimented with the possibilities of using glass without melting it, on intermediary material surfaces such as acrylic, paper, soil, charcoal, powdered paint, and plants. The way the glass particles carry the light, and the semi-transparent paste formed when mixed with acrylic and other materials, allowed me to create the layers and surfaces I wanted.

While images intertwined with nature—such as dragonflies, mushrooms, leaves, thorns, flowers—are at the center of the exhibition, you reject the representation of nature and invite nature itself into the painting. Is it possible for you to describe the difference between these two approaches?

E.A.: Yes, I think what I always sense, observe in nature, and undoubtedly see as the basic functioning of life—“emergence,” that is, “coming forth, appearing”—is possible through multiplication and assemblage. It does not matter how and in what way they come together; merely their coming together enables an entirely new emergence. I have a working practice that functions this way.

As the curator of the Pánta Rheî / Works 2021–2025 exhibition, how did you structure it? Each floor seems to contain a different story; could you elaborate on your approach? How did the works interact with the historical architecture of the building?

Levent Yılmaz: I met Elvan Alpay in 2021. Of course, I knew her works; in fact, I had seen some of her exhibitions that she opened in Ankara at Zon, Döne Otyam’s gallery, whenever I had the opportunity—but we had no acquaintance at all. As John Lennon says in “Darling Boy,” “life is what happens to you while you are busy making other plans”—that’s exactly how it happened. We met in 2021 and never separated.

“These ‘works’ were emerging not merely through what appeared on their surfaces—though that existed as well—but rather through the very functioning of the form-creating process we call nature.”

When we met, Elvan Alpay was trying to move away from the material she had used in her exhibitions in 2018–19; she was experimenting with new materials. But these overlapped with her fundamental patterns as well: that is, self-repeating figures and an intense “wild nature.” When she shifted to the use of glass powder and acrylic, this figurative world moved to another level. Therefore, from this period onward, I think Elvan Alpay departed from the classical mimesis system of Western art. You might say she had already departed—with Pollock, Kosuth, and so on—but in what we call the “conceptual” art system, the work we see almost “disappears”; a mental image needs to be presented. I say “mental” deliberately: The “work,” “piece,” whatever you call it, became a “medium,” and our mental construction had to surpass the work. Alpay’s rupture is not this. She left that mimesis order with these works; they are not “conceptual” either. So what are they? This is what I observed: These “works” were emerging not through what appeared on their surfaces—although that is also there—but rather through the very functioning of the form-creating process we call nature. The painter here was a “part.” That is, she did not exercise domination over the work. She steps back, foregrounding the functioning at the smallest level of nature, that is, quantum-level uncertainty (Heisenberg’s much-loved principle).

The series that began in 2021 was completed in 2025. In between came the 2024 Dubai exhibition, a continuation of the 2018 exhibition. The works were being produced simultaneously. Therefore, within the three floors of Sevil Dolmacı Gallery’s Villa İpranosyan, an old Armenian mansion, where you cannot touch the restored walls or ornamentation and cannot even hammer a nail, it was necessary to present these three periods together. The top floor, the third floor, had a relatively low ceiling. While installing the exhibition, it was necessary to isolate this floor as much as possible, freeing it from light and bright colors; thus the drywall was painted matte black. Lighting became minimal (one spotlight per work), and in the background, a continuous piece of period music: From The Dark Side of the Moon, “On the Run.” This floor consisted of the early works in which the new material was being tested.

On the second floor, works from the intervening Dubai exhibition (Game Over. Let Us Stop Now.) were brought together with the beginnings of the latest works that had started to be produced simultaneously. This was to show how these two different approaches were actually built upon the same fundamental questions. On the ground floor, the entrance floor, were the latest works in which the use of material became truly liberated, even giving the impression that perhaps the paintings were making themselves. As I said, in a space outside the classic gray-floor white-wall square gallery cliché, these works produced another kind of “aura.”

In the exhibition spread across three floors, the figures are more distinct on the top floor, their forms more legible; as one descends, the forms seem to preserve themselves while becoming more abstract with the layers above them. How do you interpret this transition?

E.A.: A very correct observation. As you know, this exhibition encompasses nearly four years of production. 2021 was a period right after the pandemic had ended, when we could imagine that life could continue from where we had left off, even when we could fall into the illusion that nature’s breathing had been noticed by all humanity with the decrease in production and consumption.

“The last four years we have lived through have gradually, and with increasing intensity, left us in the midst of a completely unpredictable change.”

The last four years we have lived through have gradually, and with increasing intensity, left us in the midst of a completely unpredictable change. Ongoing wars, the genocide in Gaza taking place before the eyes of all humanity, climate catastrophe, economic collapse, and the fragmentation of a shared reality we all feel is a highly abstract situation; we are in a time period where it seems there is nothing more tangible to hold onto than uncertainty… In this period, the fact that my paintings naturally emphasize this uncertainty perhaps explains the turn toward abstraction.

L.Y.: I think—though I do not know what Elvan thinks—that in addition to what I said above, I can say this: These works are not abstract; they are very concrete. They are not conceptual either, because they do not point to anything other than what we see. The painter’s mastery has withdrawn in these paintings. As I wrote, “things are taking place” in these works. Let me add this: The naming Pánta Rheî was my idea. I wanted to return to Heraclitus, to the first physicists of Ancient Greece, and try to understand these clichéd and extremely difficult fragments again. I realized something: Heraclitus has no formula like “Pánta Rheî.” This “slogan” is invented by those who came after him. The fragments I read (from the new translation by Laks and Most) pointed more toward things leaping out of the boiling cauldron of physis, whose contents we do not know—things that suddenly become visible. That is, how the non-existent suddenly becomes what exists, then disappears, and something else leaps forth (leaping is an important verb—look at Elvan Alpay’s works, the figures “leap”). For this reason, I think the phrase Pánta Rheî, translated as “everything flows,” should be understood as “things take place.” Looking this way, we suddenly find ourselves in the quantum world, in the world of John Bell’s “beables”: a world of things whose existence we know only when they exist; when they do not exist, we do not know what they are. In this sense, I do not think Elvan Alpay fully knows where she is going either.

In Pánta Rheî, works from your Dubai exhibition Game Over. Let Us Stop Now. are also included. When one considers the color palette and technique, this series can be interpreted as completely different from the rest of the exhibition, yet its logic and discourse seem the same. The years of the two series are also intertwined. How do you interpret this simultaneous transformation in your works?

E.A.: Game Over. Let Us Stop Now. was merely a continuation of the 2018 exhibition Game Over. In this period, when I changed my gallery after many years, my new gallerist suggested an exhibition in Dubai. I wanted to reserve my new production for Istanbul, and I entered a multi-production process I had never experienced before. On one side, I was making the paintings you see in this exhibition; on the other side, I was doing preliminary studies for an entirely new technique and material that interested me greatly and that I hope to share in the future. Producing works with a technique I was very familiar with was, in itself, a different experience for me.

“As you said, although the effect is very different, these are works with a very similar production logic.”

As you said, although the effect is very different, these are works with a very similar production logic. Nature seems like that to me as well—an infinite variation made up of three (and sub-) particles inside an atom, after all.

I have been accused of changing too much, and this has always seemed very funny to me. I think Levent included the paintings from the Game Over series in the exhibition because he found it effective in showing this production logic.

Between Game Over. Let Us Stop Now. and Pánta Rheî—whose name comes from Heraclitus’s expression “everything flows”—there is a conceptual transition. It feels as though even if the old game is over, there is a turn toward another existence whose rules are more ambiguous and whose movement is more subtle. How do you evaluate this transition?

E.A.: Exactly as you said, we feel that we are right at the center of a turn toward another existence. Experts agree that there has been no other period in which the evolution of the global economy, forms of governance, cultures, and local climate conditions have been so uncertain; some even describe this period as transformative for humanity on the scale of the discovery of fire. This transformation is extremely rapid; we are inside it, and we have no idea what life is evolving into—no one does… How do we cope with the increasing meaninglessness of trying to hold onto the truths we know?

There is also a book containing most of the works included in the exhibition. Your text “Notes on the Works of Elvan Alpay” provides a comprehensive framework for both Alpay’s artistic practice and its place and references in art history. You touch on many topics, from what is natural in Alpay’s artistic practice to her references in Ancient Greece, and to what she points to when she says “game over.” Could you speak about the story behind the book?

L.Y.: The starting point of the book does not lie in a single moment, but in an accumulation created by reading and re-reading Elvan Alpay’s practice piece by piece over the years. Alpay’s works at first glance draw one in with color, form, and vibrancy; yet behind that bright surface lies a very ancient, almost primordial way of thinking. Her question about what is natural goes back to the understanding of physis in Ancient Greece. Over time, I realized that this recurring search for the “language of nature” in Elvan’s works connects both the nature debates of contemporary art and the fundamental questions of early intellectual history.

The idea of the book was born exactly at this intersection. As the readings and notes I prepared for the exhibition expanded, I felt that what was missing was not merely a text to accompany the exhibition but also an intellectual framework that followed Alpay’s practice across a long trajectory. Therefore, Notes on the Works of Elvan Alpaybecame not a catalog text but an attempt to map the space that opens with her art: naturalness, artificiality, play, repetition, transformation, duration… And of course the aesthetic and ethical rupture implied by the sentence Alpay herself formulated: “Game over. Let us stop now.”

What Alpay pointed to with this sentence, in my view, was more a state of noticing than a finished game: the desire to step outside the cycle of speed, consumption, and exhausting repetition created by humans themselves. This is not merely a personal stance of an artist; it also points to a wider context in which various breaks in art history, critiques of modernism, and contemporary ecological sensibilities intertwine. For this reason, the structure of the text is multilayered: It tries to think together the possibilities of art history, philosophical references, and Alpay’s own inner rhythm.

In the end, the book emerged as an effort not to be an “appendix” accompanying the exhibition, but to make visible the invisible backbone that carries Elvan Alpay’s production spreading across many years. In a sense, I can say it is a call text that attempts to respond—within writing—to the movement, the flow, and the continual state of becoming in her works, that is, pánta rheî.

The exhibition can be seen at Sevil Dolmacı Gallery until January 3, 2026.