On the eve of the fifth anniversary edition of the Skopje Poetry Festival, the Macedonian audience has a rare opportunity to meet one of the most intriguing and interdisciplinary poets on the contemporary Turkish and global scene – Nihat Ozdal. Ozdal, known for his ability to bridge the boundaries between poetry, visual art, music, and sensory experience, will be a guest at the festival, which this year will take place from April 24 to 26 at several locations in Skopje, including the Youth Cultural Center, the “Bukva” café-bookstore, and the “Blaze Koneski” Faculty of Philology.

The festival, under the motto “From Rhythm to Algorithm,” explores the pulse of poetry – from the intimate rhythm of the heart to the urban pulse of the city, as well as the transformation of language into new, digital codes. In this context, Ozdal’s poetry stands out as a bridge between tradition and modernity, between the material and immaterial, between the word and the senses. Particularly significant is that his book “Traces of Wings” has been translated into Macedonian, enabling direct dialogue with the local readership.

Ozdal’s visit to Skopje is not just another international appearance, but a true cultural event: he will perform at the official opening of the festival, participate in poetry readings, and present the exhibition “The Scent of Words,” where perfumes become an extension of poetic language and an exploration of the question: if words had their own scent, what would poetry smell like? This unique approach to poetic creation enriches the festival program and opens new perspectives for understanding poetry as a multisensory experience.

Ozdal, whose poetry often deals with themes such as identity, memory, fabrics, and the body, brings to Skopje a poetics that is both deeply personal and universal. His participation in the Skopje Poetry Festival is an opportunity for the Macedonian audience to get to know a poet who is not afraid to experiment, to challenge the boundaries of genre, and to turn poetry into a living, sensory, and communal experience. In this interview, the focus will be precisely on his poetic thought, on the significance of poetry in the contemporary world, and on his expectations from his visit to Skopje.

Your poetry often moves between the sensory and the symbolic – how do you perceive the relationship between the word and the senses, especially in the context of the exhibition “The Scent of Words” that you are presenting in Skopje?

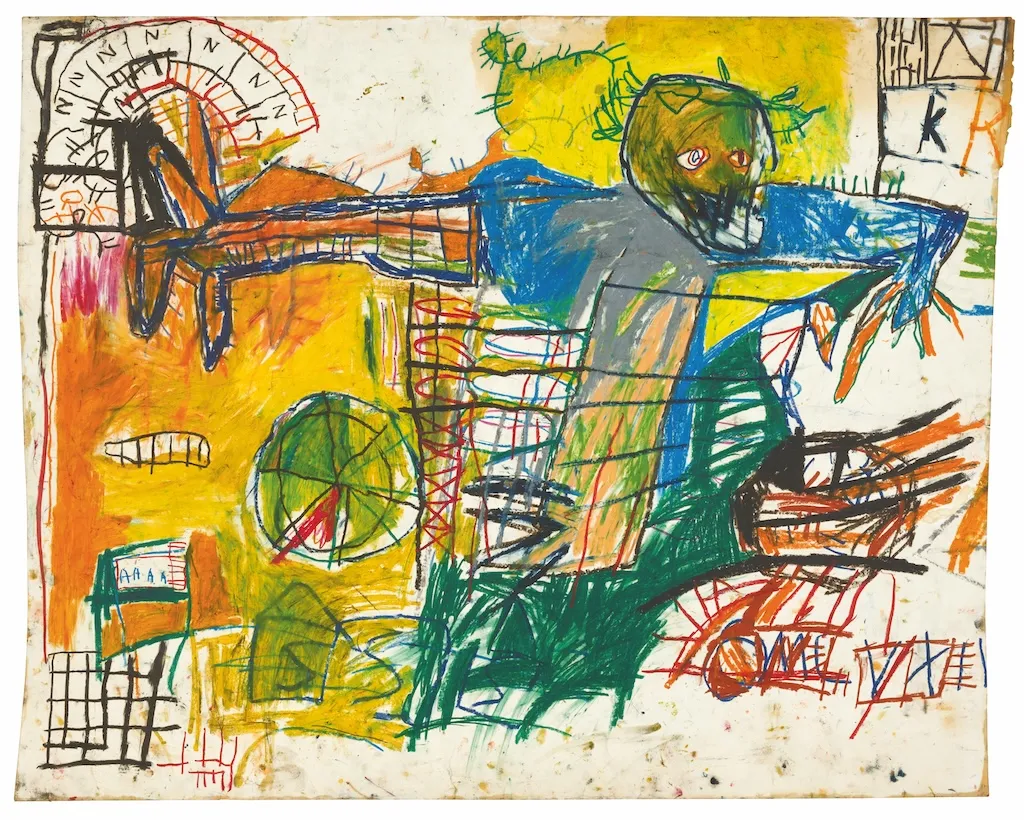

For me, language is not confined to grammar or syntax—it is a terrain of sensation. Words carry temperature, texture, weight. In “The Scent of Words,” I wanted to challenge the hierarchy of language by letting scent—often considered primitive or secondary—speak. Smell bypasses rational processing and reaches memory, emotion, and the body directly. This exhibition asks: what if language didn’t pass through the mind first? What if we felt it before we understood it? In that sense, poetry becomes not just read, but breathed in.

The motto of the Skopje Poetry Festival is “From Rhythm to Algorithm.” How do you experience the rhythm of poetry in the digital era, and can poetry retain its pulse in a time of rapid information and algorithms?

Rhythm is not merely a poetic device—it is a mode of existence. Our heartbeats, our steps, our breath—all are forms of rhythm that precede language. Algorithms, while mathematical, also have rhythm, but it is a rhythm devoid of vulnerability. I believe poetry survives precisely because it resists optimization. It doesn’t aim to be efficient; it aims to be true. In an era of compressed time and flattened language, poetry can slow us down. It reminds us that the pulse of being cannot be digitized without loss. So yes, poetry can retain its pulse—but only if we let silence and slowness return to our lives.

This question resonates deeply with a recent project of mine—Dans, a sound-poem released both as a vintage cassette and across all digital music platforms. I wanted to test the tension between analog slowness and digital immediacy, between the tactile and the intangible. Dans is not merely a recording; it is an archive of the body, a poetic resistance to forgetting. In a time when algorithms increasingly shape our listening habits, Dans invites the audience to rewind, to pause, to listen with the body. It suggests that even within the digital, there is room for ritual, for silence, for the rhythmic irregularities that define what it means to be human.

Your poetry book “Traces of Wings” has been translated into Macedonian. What does the encounter with the Macedonian audience mean to you, and what are your expectations from your appearance at the Skopje Poetry Festival?

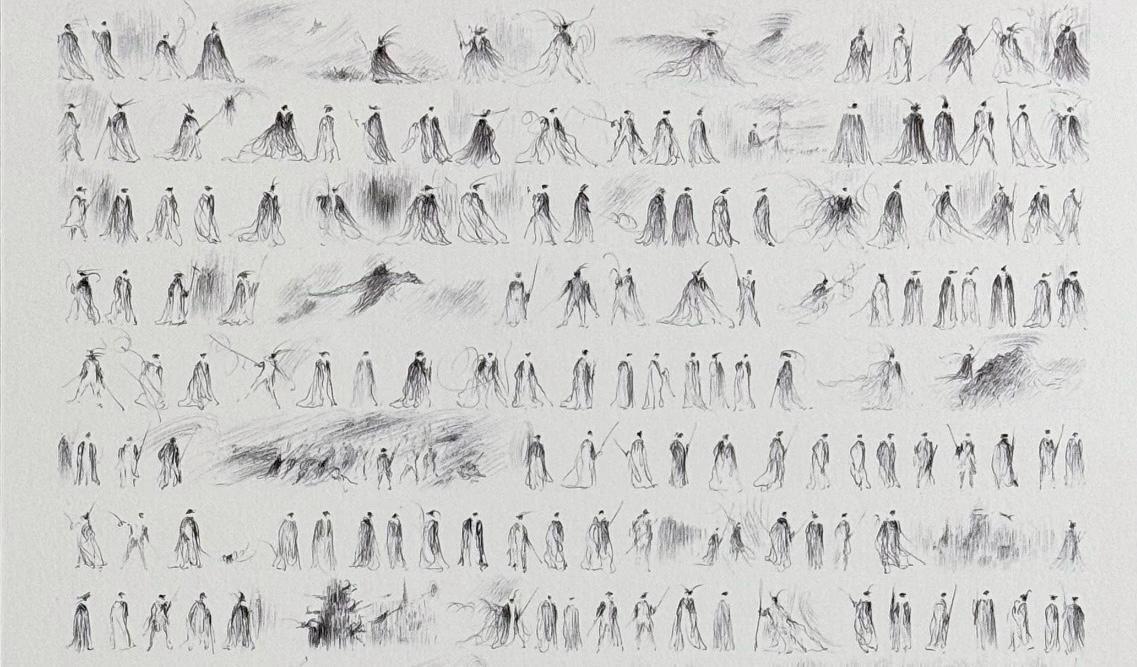

Traces of Wings was my second poetry book—one that leans toward the form and spirit of haiku. It’s a quiet book, filled with birds. Not just as symbols, but as presences. Their migration routes, the wetlands they rely on through summers and winters, the fragility of these ecosystems—these have long been at the heart of my poetic and ecological life. I have fought for their protection both in my country and abroad. Birds are not only part of my poetry, but they wander through my home, my dreams, even my daughter’s earliest language. One of the first five words she ever spoke was “bird.”

This book, named after the movement of wings, was translated into Macedonian eight years ago. In a way, like a bird, it arrived in Skopje before I did. And now, to follow that book here, to meet the land and language it landed in—it moves me. This encounter is not just literary; it is emotional, migratory, even migrational. I don’t come here as a poet presenting a book—I come as someone catching up to a part of myself that flew ahead.

At the festival, you will perform alongside poets from different countries and poetic traditions. How do such poetic encounters influence your work, and can poetry be a universal language, beyond the boundaries of cultures?

A few centuries ago, poets and travelers were often the same person. Even today, I believe poets still travel more than most other artists—not only physically, but imaginatively. I curate a project on the river I was born near, the Euphrates, called River Passengers. Through this initiative, I journey with poets from different countries along the river, allowing poetry to flow in dialogue with geography, history, and shared silence.

The Skopje Poetry Festival gives me another opportunity to meet poets from diverse traditions. These encounters are more than exchanges of words—they’re windows into other temporalities, other ways of sensing the world. I find them deeply enriching, not just for myself, but for all involved. It reminds me that poetry thrives in motion, in the spaces between languages, and in the pauses between lines where one poet listens to another.

In your work, poetry often appears as a space of freedom and experimentation. How do you see the role of the poet today – is the poet a chronicler of the times, a rebel, or an explorer of new sensory and linguistic horizons?

The poet, if anything, is an anomaly. In a world obsessed with clarity, control, and speed, the poet dares to dwell in ambiguity, in slowness, in doubt. I don’t believe in singular roles—chronicler, rebel, explorer—they are all masks that poetry sometimes wears. But beneath them, the poet remains a listener. A medium. Someone who holds space for what cannot yet be named. In that sense, poetry today is not about providing answers, but about protecting the questions—especially those that algorithms cannot compute and politics often erase.