Born from a spontaneous idea, 160 m2 is a collective exhibition initiated by Nezaket Ekici brings together seven artists in a harmonious assembly. Taking place in an empty apartment in Antalya, it transcends traditional exhibition spaces, transforming into a collective realm for creation. In this exhibition, every unit and corner of the home is utilized for artistic dialogue. This unique space doesn’t merely invite viewers to witness an exhibition but welcomes them as true guests, creating a sense of community and shared creative spirit.

Ranging from painting and installation to performance and video, various disciplines intermingle, gaining new layers of meaning through audience participation. 160 m2 emerges not only as an exhibition but as an innovative experience, revitalizing the collective power of art, the spirit of space, and human connection.

Tuğçe Arslan: 160 m2 is one of your fascinating experiments, spontaneously conceived. Could you share a bit about how this exhibition developed and the motivation behind its creation?

Nezaket Ekici: It all started quite simply. I have an apartment in Antalya, which I recently put up for sale, so it’s currently empty. Last week, I visited Antalya to see family, and while I was there, I decided to take a look at this apartment. When I stepped inside, I was struck by the emptiness of the 160 m² space. I thought, ‘I need to do something here before it’s sold.’ I had even brought a costume from one of my performances, ‘Tube,’ with me from Berlin, just in case inspiration struck.

I didn’t have much time in Antalya, as I needed to head straight to the Sinop Biennial afterward for a performance during the opening. So, in this short window, I decided to perform Tube in this large, empty space, but I didn’t want to stop at a solo performance. I imagined a group exhibition. Then, I asked myself which artists I could invite on such short notice. I remembered that in 2017, I was invited by curator and academic Ebru Nalan Sülün to Akdeniz University, where she introduced me to colleagues and local artists. We all became friends and stayed connected, and over the years, Ebru has brought many of us together in exhibitions in Antalya.

So, I reached out to my artist friends—Handan Dayı, Kemal Tizgöl, Işık Aslıhan, Ilgaz Özgen, Gül Yasa, and the young artist Güneş Aslıhan. I sent them all a voice recording, quickly describing the apartment, my idea, and my tight schedule, urging them to respond if they were interested. Soon, messages started coming in—they were intrigued. We met online that evening and the following nights, discussing the details. Initially, everyone was concerned about the time constraints, so we decided to make it a Pop-Up exhibition. Pop-Ups are very common in Berlin, so we thought, ‘Let’s see how it works in Antalya.’

From there, we meticulously planned the exhibition, aiming to bring together a variety of media—painting, photography, installation, sculpture, video, and live performance. I also went around to each neighbor, knocked on their doors, and invited them. They were very interested, and they all came and loved it. In short, it all began with me seeing the empty apartment. That vast, vacant 160 m2 space captivated me, and I felt it needed to be put to creative use.”

T.A.: It seems the main theme and inspiration of the exhibition is this home itself, right? In that case, I’d love to hear from you about how the concept of ‘home’ resonates in this particular exhibition.

N.E.: First of all, let me say that it was essential for it not to be just a ‘White Cube’—a blank, sterile gallery space. This is a home, distinct from traditional exhibition venues. It’s fascinating to think about who might have lived here before, who left their mark, who became part of this space. So, the home has a character, and that’s significant. Unlike museums and galleries, a home uniquely welcomes everyone. There’s a living room, a balcony, a bathroom, a kitchen… It’s an intimate space that warmly accepts those who enter, almost like hosting guests. It’s inviting and authentic—‘interior’ in the truest sense of the word.

I’ve worked with the home concept before: I did First Contact in New York and Germany, and in 2000, I remember my first solo show, Werkschau, at Galerie Weisser Elefant in Berlin, which was almost like my own apartment—a vacant space used as a gallery. Of course, those performances were different, but here, the significance lay in the emptiness of the space, yet it carried an aura full of memories. It was a dynamic, energetic, and fresh place for everyone. As artists, we were almost like hosts, welcoming guests in an exhibition space. We greeted visitors at the door or saw them off. It created a new type of exhibition model, fostering a unique relationship between artists and viewers.

T.A.: In this exhibition, you’ve re-enacted your performance, Tube (Tüp). Could you briefly describe the theme of this piece and explain how re-staging it in this space affected the process and impact?

N.E.: Tube (Tüp) was first performed in 2008 in Toronto, Canada. As an artist with a background in art history, I often draw from art historical themes. This performance is inspired by the female figure in Otto Dix’s 1925 painting of Anita Berber. Tube (Tüp) also incorporates the concept of time, spanning past, present, and future. When I first performed it in Toronto, I conveyed this temporal expanse by projecting a video that repeated my image over time, accompanied by light and shadow techniques. I aimed to recreate these elements here in 160 m2. However, the apartment’s living room is different from a gallery space—it’s large for a home, but not as spacious as a traditional exhibition hall, so the space was somewhat limited.

Yet, a different sensation emerged here. Let me start with that: first, there’s a connection between the idea of a home and the costume I wear in Tube (Tüp). A costume or garment is something we wear to wrap around and protect the body. As you can see from the visuals, the costume in Tube (Tüp) similarly envelops my body. Similarly, a home surrounds and shelters us, taking us in and providing a personal refuge from the outside world. This created a new imaginative dimension for Tube (Tüp) within the context of the home. I performed it in the living room as if hosting visitors right there in that intimate space. I also included the video piece I used in Tube (Tüp), presenting it in a living room setting.

Just as many homes have a television in the living room for family gatherings to watch films together, the projection here created a similar moment of convergence. We turned this living room into a live ‘home cinema,’ and together we watched my video set in a snowy landscape. Lastly, it’s worth mentioning that, in contrast to the snowy scene in the video, the performance space was quite warm—Antalya still feels like summer this time of year. This contrast between the snowy imagery and the warm reality added an extra layer of tension.

T.A.: How did the collaboration process with the other artists in the exhibition unfold, and what common themes did you focus on? Also, how did the space of the home shape your work and serve a purpose in exhibiting it?

N.E.: As I mentioned earlier, we started with an idea, communicated, and made a plan. I then filmed the empty apartment and sent the video to the artists. We decided that every part of the home should be used—no area left untouched. Using the video as inspiration, ideas began to form. For example, Ilgaz wanted the bathroom, as it suited the nature of her work perfectly. Several people were interested in the living room, but I needed it since my dress was long and wouldn’t fit anywhere else. Handan found the corridor ideal for her work, as corridors traditionally serve as spaces where family photos are displayed, bridging past and present. Işık’s fish pieces resonated with the concept of the home as a place holding water. At first, we thought of placing her work in the kitchen, but we ultimately decided on the balcony.

Gül needed a larger room for her paintings and cartoons, while Kemal’s installation, which involved large stones wrapped in fabric and photographs, required a lot of space, though the apartment couldn’t accommodate everything he planned. Güneş’s projection piece, meanwhile, needed an intimate setting, so we designated a small room for her work.

This was the general process. Each artist connected the theme of their work with a part of the house and selected a location in 160 m2 that matched both the character of their work and the needs of the space. The result was a harmonious arrangement where our works engaged with the essence of the home itself.

T.A.: Handan Dayı, your piece Zamansal, which comprises family photographs on transparent material, seems to touch directly on the concept of time. The images’ transparency evokes a presence that is both there and not, symbolizing the gradual disappearance of things over time and the paradox of never fully disappearing. This work relates directly to the concept of ‘home’ through experiences, those who’ve passed, and new arrivals. Could you elaborate on the setup of your work in 160 m2 and how you approach this relationship?

Handan Dayı: Hello, dear Tuğçe. I studied photography in university, and what captivated me most about the medium was discovering its connection to time. Perhaps that’s why time has become a central theme in my work. Zamansal consists of four generations of family photos. These images, printed on transparent vinyl and displayed in chronological order, were hung in the corridor. As you noted, the work alludes to presence and absence. The portraits, layered to be seen through one another, are of family members—some of whom I never met but whose genes live within me. Their existence continues in my body, offering a different perspective on mortality. Their photographs, luckily, are here.

Choosing the narrow, long corridor for display compelled viewers to interact with and, in a sense, ‘meet’ the entire family. The corridor’s extended architecture acts like a ‘passage,’ alluding to the ontological flow of time. As viewers navigate the corridor, they are invited to reflect on life’s transience, the presence and absence of existence. In this empty apartment, the very notion of absence allows us to reconsider existence through the lens of absence itself.

T.A.: Kemal Tizgöl, your work Unfamiliar (Yabancı) was previously displayed in an open setting, on a beach. It consists of stones held together by a fabric that, despite the rigidity of the stones, allows them to remain spaced out and flexible due to the fabric’s pliability. This adaptability enables the piece to be arranged in different spaces and forms. The title Unfamiliar hints at themes of foreignness, belonging, and, implicitly, identity. How does this installation reflect these themes in its current setting?

Kemal Tizgöl: Unfamiliar (Yabancı) resembles a living being that adapts to its environment, shaped by the ‘place’ it inhabits. It never truly belongs anywhere, always maintaining a temporary relationship with the space around it. Just as it could encircle a large rock on an expansive beach, it finds a place for itself in a vacant room of an abandoned house. The inherent contrast between the stones’ solid, heavy nature and the fabric’s lightness and softness emphasizes a sense of alienation that is also conveyed to the viewer. This juxtaposition intensifies the feeling of foreignness.

In its essence, this piece holds autobiographical elements, exploring the personal experience of seeking reconciliation with one’s surroundings—a search for belonging or the experience of not quite fitting in. Unfamiliar questions the individual’s efforts to negotiate their place within society, presenting a reflection on identity and the human desire to find or create a sense of home.

T.A.: Işık Aslıhan, your work On the Trail of Fish: Human and Water is composed of artificial fish. Before diving into my question, I’d like to commend the coherence of using representations of animals instead of live or deceased creatures to examine the relationship between nature and humanity. Unfortunately, some artists paradoxically utilize animals in ways that contradict their critiques of anthropocentrism. Turning to your work: among the static, gray fish lies a single, vibrant red fish, seemingly struggling. This hints at its being the sole ‘alive’ fish among the gray, lifeless ones, yet the fish’s arrangement to form a human body suggests that, amid life’s dullness, there’s a flicker of vitality, excitement, or a hint of escape. How does this piece center on the relationship between nature and humanity, and how do you approach the themes of humans, water, and nature in this work?

Işık Aslıhan: Human beings often place themselves at the center of the world, believing everything exists for their benefit. Instead of harmonizing with nature, they attempt to reshape it thoughtlessly. The result is a tremendous loss. In reality, nature’s destruction signifies humanity’s end as well. The most critical element of life is water; water may not vanish, but it can lose its life-sustaining quality. Without water, there is no life.

In On the Trail of Fish: Human and Water, I depict the relationship between water and humanity through a composition of fish forming a human figure. The single moving fish among the gray fish represents the heart of a dying human. It stands at a crucial moment: will it perish, or will it be allowed to live, multiply, and sustain life? This work invites viewers to reflect on their connection with nature, urging them to reconsider humanity’s dependency on and relationship with the natural world. It’s a reminder of the delicate balance and interdependence that exist between human life and nature.

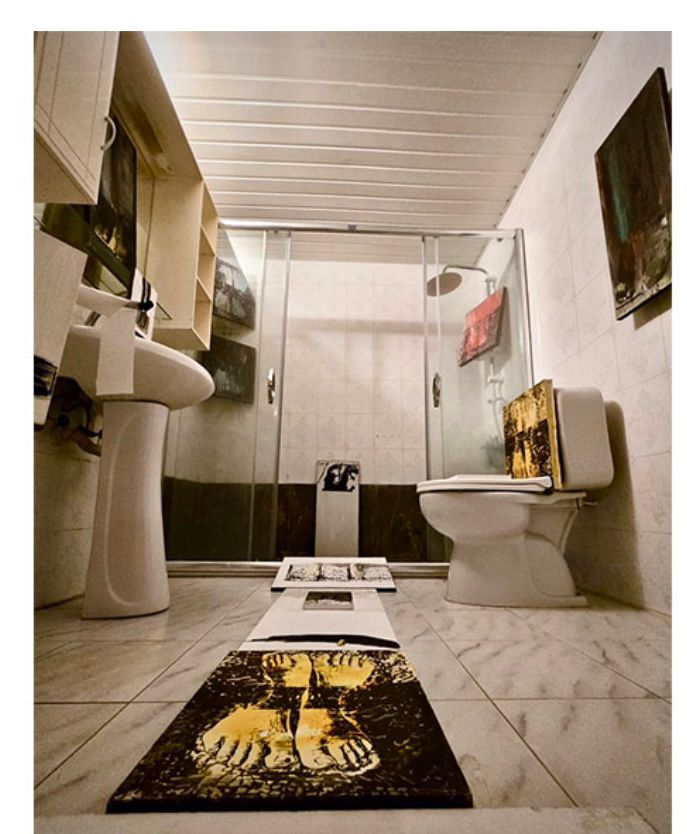

T. A: Ilgaz Özgen, in your installation From the Outside, Inside… To Myself, located in the bathroom of the 160 m2 space, various foot figures are arranged in a specific sequence. You specifically chose the bathroom for this placement. The feet, thus, seem to establish a relationship between the private spaces of the home, like the bathroom, and the human body. This also brings forward ideas of purification and being alone with oneself. How does this piece address the concepts of purification and the body?

Ilgaz Özgen Topçuoğlu: In From the Outside, Inside… To Myself, the image of feet stands as traces of our daily lives and as the carriers of our bodies. Additionally, the bathroom, a private space in the home, becomes a part of this installation. As we know, in the artistic creation process, the era we live in, along with the artist’s own experiences, often transforms into an artistic expression. In this context, the foot image represents not only the traces of our bodies and lives but also carries and is a part of my own lived experiences.

Furthermore, the foot image is a kind of portrait of my sister, Gülgez Özgen, who lost her fingers and toes at the age of thirty-three due to a capillary disease that caused gangrene. Despite the intense pain caused by her illness, she stood tall, and she holds a special place in my life. The installation, set in the bathroom—a private space where we are alone with ourselves—becomes, through the medium of water, a space for a certain purification from daily life, self-confrontation, and reflection on the ‘memory space.’

T. A: Gül Yasa, Mee Generation is a rather ironic title. It seems to transform your work into a reactive voice. Additionally, you aim to point out the political wrongs and pressures of our time, along with reactions and passivity. Does your focus on farm animals tie into the idea of societal ‘manipulation’?

Gül Yasa: Yes, I would say it’s about both manipulation and being manipulated. I believe that the current generation (or age) is one of ‘Imposition’ and ‘Imitation,’ and I shape my works around this idea. Through animal portraits, I try to emphasize the cultural stances, reactions, and passivity of people in recent times. In the 160 m2 space, the works we placed in independent areas had a common denominator related to humanity and the human condition. With the animal portraits, I wanted to critique the widespread acceptance of impositions and pressures in almost every field today, pointing out the large majority that simply participates by mimicking movements and conforming. Thank you.

T. A: Güneş Aslıhan, you participated in the Involuntary installation at 160 m2. Based on Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring, you’ve stated that this work explores the conflict between the involuntary movements of the body and societal and artistic norms. Could you expand on how societal and artistic forces shape your work’s relationship with the body?

Güneş Aslıhan: Societal norms define what is considered ‘appropriate’ by forcing the body into specific patterns and behaviors, which often manifest in the body’s movements, posture, and even expressions. In classical art, the idealized and perfect body and movements are created, which objectify the body and transform it into an aesthetic object. In Involuntary, I examine this dilemma by emphasizing how the involuntary movement of the body clashes with both artistic and societal expectations.

T. A: So, to wrap up, what are your thoughts on the impact of the 160 m2 exhibition on the audience?

N.E: They were very impressed! I can say this for sure; they were moved. The performance was announced to take place from 16:00 to 20:00, for a total of four hours. Despite this, the audience arrived early, and some even came back later. By the end of the day, about three hundred people had visited the exhibition. Neighbors, people who heard about it from neighbors, they all came. Some of these visitors were encountering something like this for the first time, and you could see the excitement on their faces. Also, the fact that it was held in a home environment didn’t make them feel like they were in a museum or gallery, so they weren’t put off by that; they didn’t feel like outsiders. They were all included, they were our guests. Real guests. Additionally, since some of my artist friends are academics at Akdeniz University, their students also came. I believe for the students, it was a different, eye-opening, exciting, and possibly inspiring experience.