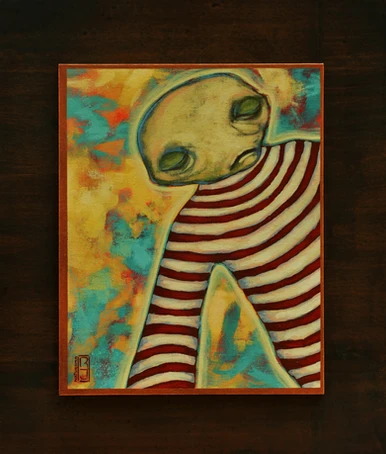

Artist Ricardo Jarama presents a surrealistic vision of a predominantly organic world, in which color and form intertwine to create a game between the rational and the irrational, between poetry and image, and between the oneiric and the visions in his sleep. By doing so, Jarama invites the viewer to discover a new kind of world, a world that connects all souls, a world that puts everything in a new wave of understanding.

What lies beneath your works, what is your motivation?

My main motivation is to try to understand the world around me. It’s the curiosity about the time and space in which we develop. It’s learning to live, connecting with my higher self, and being able to express a moment of such vast creation. It’s about understanding wise phrases like those of the poet Rumi:

“You are not a drop in the ocean.

You are the entire ocean contained in a drop.”

Private Collection

How did your journey from Peru to Athens affect your artistic practice?

It affected me in various ways. The context of my life at that time—the work and routine—was focused on art education. For some reason, the environment in which this work took place was very adverse, and I decided to leave it. On the other hand, making art and being able to live off it was difficult, and I had to take extra jobs outside of artistic work. Then came a time of radical change when I met and began a relationship with my current partner, my wife, Eirini, and with that, the birth of my first son, Constantino. We decided to settle in Athens. Along with everything I was experiencing, I also went through cultural shock. It was a difficult period—the lack of a second language affected me emotionally. I couldn’t communicate, and learning a new language like Greek and assimilating into a new culture was a challenge.

I paused for a long period, trying to find my place in time and space, reorganizing my ideas, my sculptural work, and learning to open other fields in which to develop and express my ideas in art.

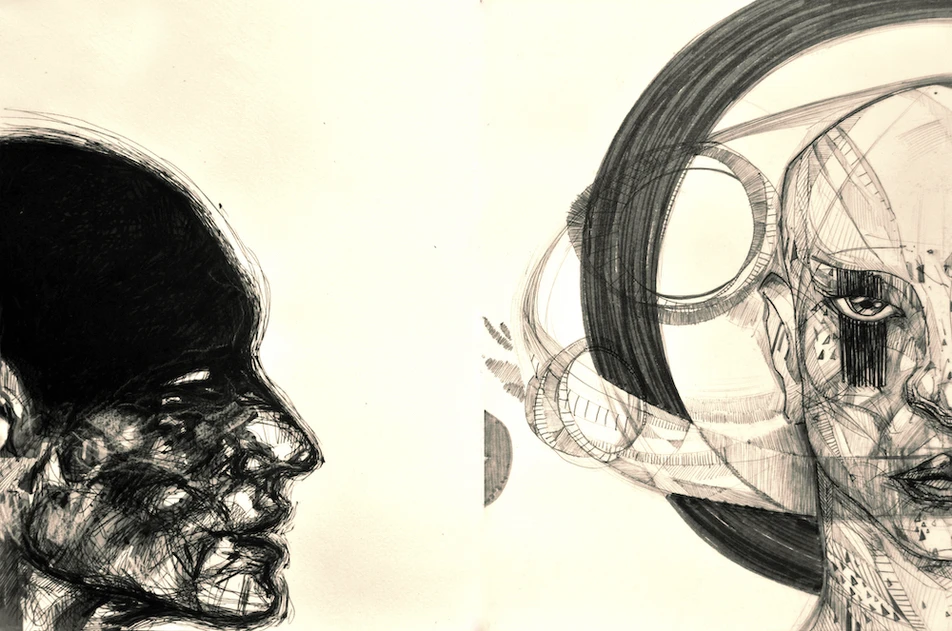

How important are sketchbooks before starting to paint?

For me, sketchbooks began as a way to organize and develop a series of ideas, establishing a concept and visualizing that concept. They became thematic notebooks for me. Each notebook I’ve produced has taught me to develop certain themes. For example, in my latest notebooks, titled ‘Future I and II’ and ‘The Super Reality’, which is still in progress, I’ve developed these ideas. Some thematic notebooks present illustrated ideas with experiments in drawing, watercolor, collage, ink, etc., which are more finished or polished. In this sense, the thematic notebook and the set of illustrations become a complete work in themselves, and their content can inspire the development of a series of paintings, watercolors, collages, sculptures, prints, etc.

Peruvian Culture in Jarama’s Works

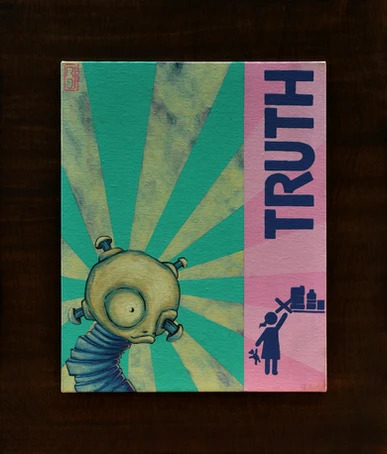

Your latest series includes figures on the robotization of humans. How do you foresee the future of humans on Earth?

I believe this refers to the thematic notebook ‘The Super Reality’, which is my latest work in progress. This is a very complex question because it would require addressing many events that are constantly changing the course of reality toward a more technological future. So, it can be approached in various ways. In my work, it’s a review and a social critique of the dehumanization of man—as a machine man, a robot, an automated being. It’s also a critique of the overwhelming growth of new technologies, including AI, as the only solution to human problems.

We need to consider what path we should take because, depending on how we think and how we wish to live, we could head toward transhumanism. Then we would ask ourselves: Are we still human? Where did all our humanity go? Perhaps, in the not-too-distant future, we’ll have those answers.

You also use symbols from Peruvian culture, such as masks. What is the significance of these symbols in your works?

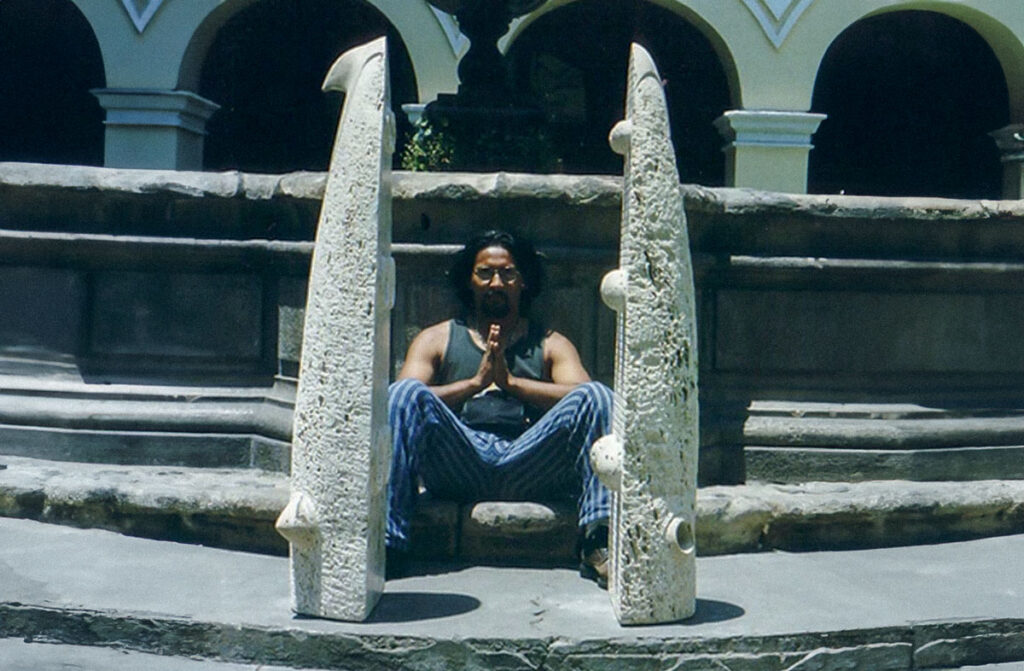

I’d like to clarify that the symbol I use is not a mask but a sculpture (monolith) found in the Archaeological Sanctuary of Chavín de Huántar, located in the district of the same name, in the province of Huari, Ancash region, Peru.

The monolith mentioned is called ‘Cabeza Clavaor‘ ’Trophy Head’. It is part of a series of sculptural monoliths that represent the heads of mythological beings on the walls, high up and around the Chavín de Huántar temple. The heads symbolize sacred animals from the Andean worldview—zoomorphic and anthropomorphic heads of a serpent, feline, and bird.

The bird symbolizes the upper world, the heavens, known as “Hanan Pacha,” and its animal is the condor.

The feline symbolizes earthly power, strength, and the here and now, and is known as “Kay Pacha. ” Its animal is the puma in the Andes and the jaguar in the Amazon.

The serpent symbolizes the underworld, associated with waters, rivers, and lakes, known as “Uku Pacha,” and its animal is the anaconda.

As sculptures that hold great ancestral wisdom and are loaded with symbolism from the Andean worlds, they are present as symbols of power, protection, and transformation in my work.

You can check out the artist’s website here.