After a career as an architect, later joining the OMA architecture studio founded by Rem Koolhaas as a partner, Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli has established 2050+, his own interdisciplinary studio in the city of Milan this year. He continues teaching at the Royal College of Arts in London. He was also a committee member for the Pavilion of Turkey at the Venice Architecture Biennale / 17th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia.

This year Ippolito curated the Russian Federation Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale, which has been postponed to May 2021, and ran an entirely online program functioning as an editorial and research project. Additionally a video project by 2050+, named ‘Riders not Heroes’, is a short video essay investigating the precarious conditions of food delivery workers in Milan. The piece received a lot of attention from the design and architecture community.

circumstances. The Open? programme of the Russian Federation Pavillion at the

Venice Architecture Biennale was one of them.

-

How would you define the moment we are living in?

If I have to use a word, I would use ‘suspension.’ In a way we are trying to deal with this global crisis but we are also on ‘stand by mode’. What is worth considering is this notion of going back to normality, which was not fine at all. It is exactly the system that puts this crisis into being. So I just hope that this crisis will steer some thinking about those structural issues that we are put into. I am also concerned that many people are overwhelmed by this situation. It’s something that is too big to describe and that is why there is a lot of waiting, in a way.

-

During the pandemic, we are all confused about the causes and consequences. But it is crucial to be aware of the real causes in order to be realistic about possible results. What do you think?

The virus comes as a consequence of our extractive and violent relationship with the planet, the constant and permanent erosion of wildlife and biodiversity. It is quite crucial to reframe our system of production. We need to look beyond anthropocentric perspectives and start thinking that we are not alone here. We need to find different or productive ways to coexist with things other than human agents.

“Architectural biosecurity is an incredible topic that will definitely reshape the system of hospitals and medical care around the world.”

A new and localized way to look at technology, supply chains, distribution and production is emerging. Consequences will also deal with scale. We need to start looking back into cities, countries or regions as a collection of interconnected smaller communities which are then intertwined on a planetary level, and that can be sustained within closer networks.

-

How you think the design and architecture industries are responding to emergency conditions, considering the actions taken in these fields during the pandemic?

I was very disappointed (and sad) during the first lockdown while browsing through architectural and design websites; seeing these kinds of projects that are made for pandemic-like design products, for new masks, separation tables, gloves, etc. In a way this is exactly the neoliberal kind of logic that brought us to this crisis.

On the other hand, there are important initiatives such as the biennial curated by Mariana (Pestana) – the 5th Istanbul Design Biennial held this year – that are looking at a different dimension, design as a tool for community making, to understand and nurture the places and the planet we inhabit. To reconnect, to go beyond the logic of mass production and mass distribution. So there is this tension between the market and more speculative and yet much more realistic operations, which is very vivid.

“I’m personally interested in new forms of labor, and the way platform capitalism has been reshaping our cities in the past years.”

This morning I was looking for the symposium organized by Princeton University and e-flux, on ‘sick architecture’. Architectural biosecurity is an incredible topic that will definitely reshape the system of hospitals and medical care around the world.

-

This year we are rethinking the meaning of home, distance, environment, control, empathy, nature, climate… How will the ‘new meanings’ shape the future of architecture?

There is a space for architecture to enter domains which were not familiar to architects before. That is very necessary. Obviously all works made in the countryside proved the need for architects to project their thinking onto something that is dominated by engineers and technical approaches.

In order to do that though, there is a need for a huge pedagogical transformation. Schools need to start thinking In different ways, to shape programs that trespass the disciplinary boundaries. That is partially the mission of many initiatives that have been launched now.

-

‘Riders Not Heroes!’ is a short video essay that you, as 2050+, launched this year. It investigates the precarious conditions of food delivery workers in Milan. It is important to make a comprehensive reading on that subject at the intersection of social and economic matters. What is the main discourse here?

I’m personally interested in new forms of labor, and the way platform capitalism has been reshaping our cities in the past years. So the idea of the video was to explore the conditions of food delivery riders in Milan during the lockdown; lying at the intersection of platform capitalism, gig-labor, the refugee crises and COVID-19. During the first lockdown the world was brutally split into two categories of people. On one side, those who had the luxury to stay at home, and the other side, an army of invisible and essential workers who couldn’t afford to stay at home. The only people you would see crossing the city were the riders working for tech platforms. They act as the last bits of a chain of automation, providing food through the interface of a mobile phone. The video essay documents the locked down city from the unique perspective of a rider, and it evolves into more political questions of precarious labor, automation and illegality.

“When the biennial officially announced that it would have to be postponed, we decided to migrate the entire program online. The overall idea of ‘Open?’ was to investigate the public role of cultural institutions in times of global crisis, through different languages and media, such as cinema, music or video games.”

We use this lens to unveil the mechanics of tech platforms, their often unfair conditions and connections to other forms of extreme exploitation. The film, for example, touches upon an investigation by local authorities into cases of gang mastering by platforms, which through the lockdown has regularly enrolled desperate undocumented migrants–who are untraceable and therefore open to exploitation–to run deliveries on phones owned by third parties. We interviewed several riders and many said that this is their only form of sustainment. In this context, platforms are not taking real responsibilities for the regulation of these new forms of labor. Their work is being regulated by artificial intelligence. They are stuck in a technological and bureaucratic void.

“Riders Not Heroes” is part of a work on the relationship between labor and technology which we have been developing since the Oslo Triennial in 2016. At that time, we did a fictional work called Panda that was looking into the impact of sharing platforms like Uber and Airbnb on our cities. Food delivery platforms are just the next chapter in this work.

-

This year you curated the Russian Federation Pavillion at the Venice Biennale 2020 and operated the programme themed as Open? How did you reshape the program due to pandemic and turn it into dialogue-based content?

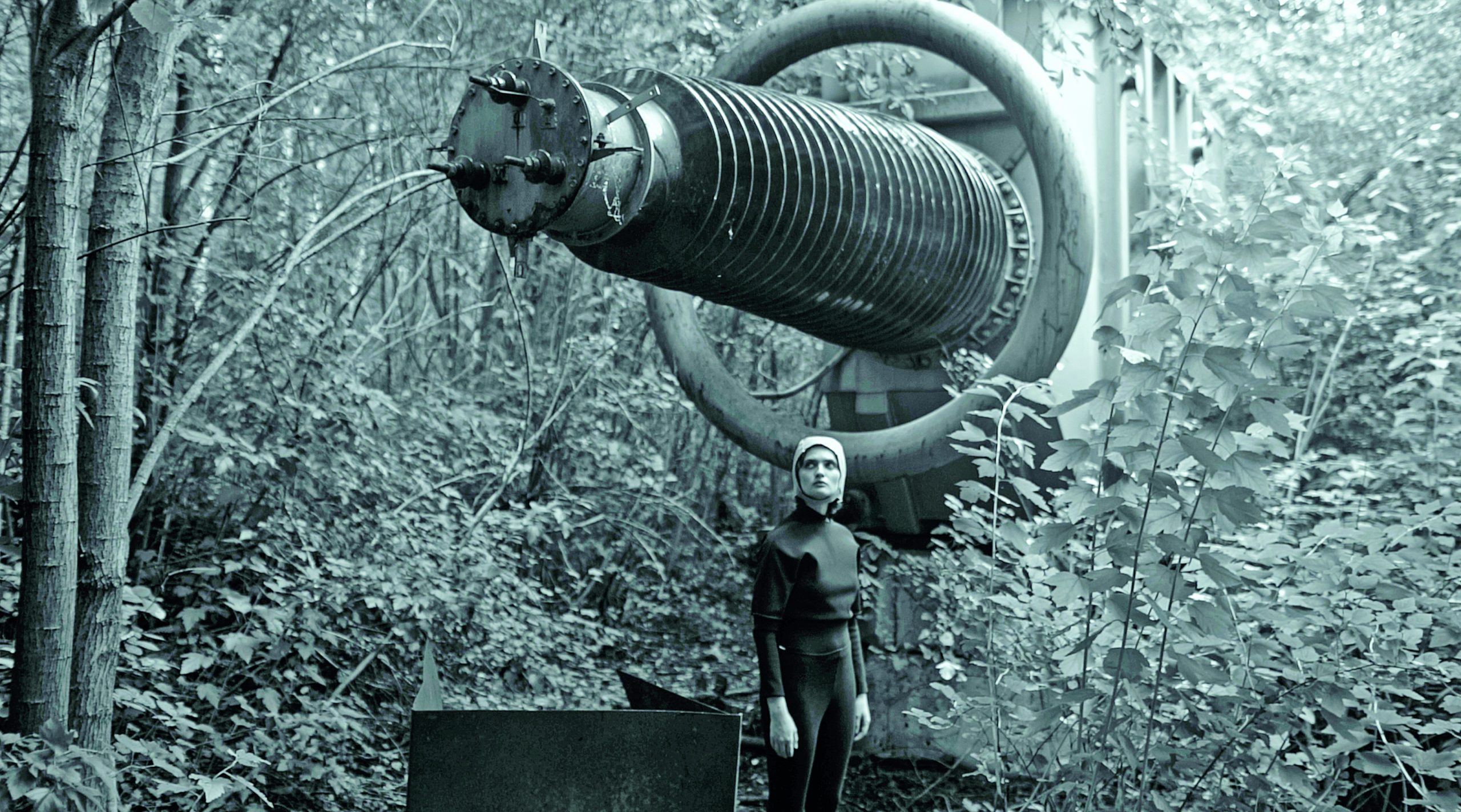

It was not meant to be an online program at first. When the biennial officially announced that it would have to be postponed, we decided to migrate the entire program online. The overall idea of Open? was to investigate the public role of cultural institutions in times of global crisis, through different languages and media, such as cinema, music or video games. By transferring everything online, Open? turned from an exhibition into a sort of open-ended research and editorial platform. We had the chance to invite more curatorial perspectives, include other points of view and to even create chapters specifically developed for the website platform. For us it became very exciting, because it was a way to respond to the evolution of the crisis. For example, a few months ago we launched an entire video game on the platform, produced by Mikhail Maximov, a wonderful game designer and filmmaker from Russia. The game actually takes place at the Russian pavilion and the surrounding Giardini, in a dystopian post-pandemic scenario.

-

This year, a lot of events turned out to be digital and online under the current circumstances. And some events, like the 5th Istanbul Design Biennial supported long-term research projects based on collaboration and dialogue. How do you think this experience will evolve curatorial practice and the future of such platforms?

That is a big question! The most interesting impact of an event or a program is its potential in establishing a network of people participating. To me, curating is mostly about defining sites of encounters and dialogues, whether digital, physical or both. Curators need to set up the conditions to allow very inclusive dialogues to happen. It is impossible to understand this if you are looking at it from a strictly disciplinary perspective, because you are then neglecting the idea of complexity on one side and of inclusivity on the other.

I was recently in a debate on the Venice Biennial. I was advocating the fact that the disciplinary division of the biennial doesn’t make a lot of sense any longer, and that it is difficult now to trace a clean boundary between design, visual arts, science, performance, environment, etc. It is all part of one single cultural understanding. Disciplinary perspectives do have a meaning, but they do not necessarily correspond to what is happening in reality. To me, it is about exiting this fiction where everything is so clear and divided. In reality, everything is more complex, more blurred, more queer.

-

Research-based practices and expanding dialogue through an interdisciplinary approach requires a sincere and sustained effort. As 2050+, how are you turning your intention to do that into reality?

2050+ is a platform made up of architects and also non-architects. Our interest is working across our politics, environment, technology and obviously design. The biggest challenge to keep everything together is to find opportunities in the private or public market that allow us to continue our investigation in collaboration with our clients. We are trying to find affinities with potential clients that understand the value of an interdisciplinary approach and that are looking beyond the need of service design.

“The most interesting impact of an event or a program is its potential in establishing a network of people participating. To me, curating is mostly about defining sites of encounters and dialogues, whether digital, physical or both.”

For instance, with Nike in Milan we have initiated the Nike Movement Lab initiative, a long-term research effort that looks at future trends of urban movement, expanding the definition of sports into body politics, self-expression, new ecologies, etc. The output of this work will turn into an editorial project. Instead of a design or architectural product, it was rather about engaging in a conversation about the need for their industry to change in order to be more political in the future.

-

What was the hot topic of this year’s discussions with Ida?

The biggest effort that we had to make is to give her an impression of safety, that everything is fine and this is not the end of the world, although it is a very severe crisis. We tried to explain basically what the virus is, why it came to be, what we can do about it, etc.? We are dealing with reality but trying to create a zone of positiveness.

-

What is the ‘big thing’ is on your mind for next year?

We are thinking about launching a unit in our office that is fully dedicated to gaming and digital world making, which is something that we are currently researching at the Royal College of Arts with our studio.