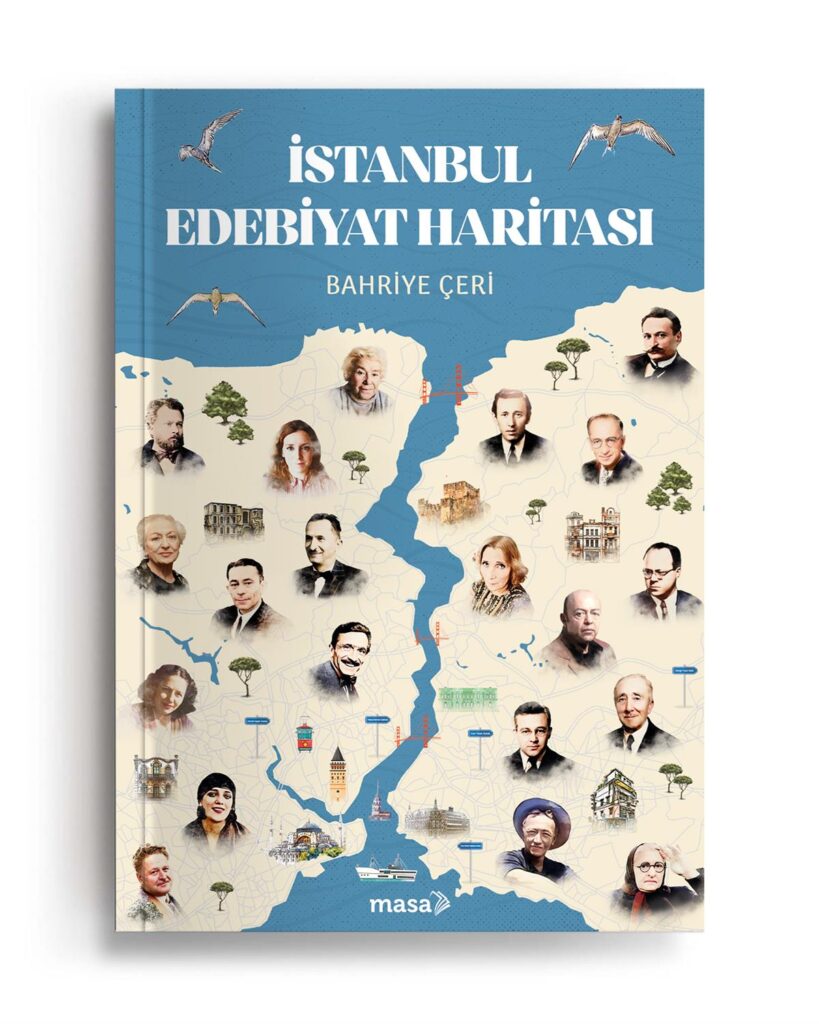

The Istanbul Literary Map is a unique work that understands a city not only through its geographical boundaries but also through its literary memory, remapping its streets, neighborhoods, lost gardens, and ruined mansions through the traces of writers. Shaped by Bahriye Çeri’s research spanning many years, the book questions the permeable boundaries between literature and space, social class and literary representation, and individual memory and collective identity. At the intersection of urban studies and literary sociology, the Istanbul Literary Map reinterprets the spaces of the past through the lens of the present, revealing the recording and resilient nature of literature. For a city is built not only with stones, but also with narratives. This map is an invitation to preserve memory for those who wish to read Istanbul through the traces of literature. We discussed all of this with Bahriye Çeri.

Let us begin with the origin story of the Istanbul Literary Map…

I had come across many books in Paris that guided readers through writers’ homes and literary spaces, and I had explored the city with these books. In 2009, Uğur İbrahimhakkıoğlu, then president of the Turkish Touring and Automobile Association, proposed the idea of a book focusing on Istanbul’s reflections in literature, inspired by the city’s designation as the 2010 European Capital of Culture. I explained to Uğur Bey, a lawyer who loves literature and has a master’s degree in the field, that such a work was lacking for Istanbul, drawing on the examples from Paris. He accepted the suggestion, and the Istanbul Literary Map, modeled on the Paris guides, was published. The first edition sold out quickly, but it had shortcomings due to being prepared in a hurry. I hoped it would be revised and reprinted, but neither the institution reprinted it nor did a similar work get published. I, however, did not give up on the subject. I noted down every address in biographies, letters, and memoirs. Thus, this book emerged, three times richer than the first edition, more comprehensive and improved.

Did you start seeing Istanbul differently during this process?

Yes, during this work process, I started seeing Istanbul not just as a city where people live, pass through, or consume on a daily basis, but as a layered place with a memory, a place where every street carries a literary trace. I discovered a completely different side to neighborhoods I thought I knew well. My relationship with the city has become more attentive, more emotional, and more questioning. Before stepping into a street, I find myself thinking about who has walked there, which literary character has passed through it.

How do you see the relationship between the neighborhoods where writers live in Istanbul and their social classes?

Istanbul’s neighborhoods carry not only geographical but also class, cultural, and ideological meanings, and they still do today. This multi-layered structure has been a powerful factor in determining both the living spaces and the literary worlds of writers. Let’s look at the late Ottoman period, when literature was largely in the hands of the elite. Halit Ziya Uşaklıgil’s houses, Recaizade Mahmut Ekrem’s relationship with the Bosphorus mansions, or the places where Abdülhak Hamit Tarhan lived… This period shows that writing was intertwined with an aristocratic or at least upper-class position. Literature, in a sense, spoke the language of the elite. Of course, there were writers who lived simpler, more modest lives outside this trend. However, the general trend shows that literature was intertwined with class privilege. In the early years of the Republic, neighborhoods such as Nişantaşı, Teşvikiye, and Şişli were home to the new bourgeoisie and urban intellectuals, while areas like Kadıköy and Moda hosted an intellectual yet bohemian literary circle. More conservative neighborhoods like Üsküdar and Fatih, on the other hand, were areas where writers who connected with traditional narratives found inspiration.

“The example of Orhan Pamuk is striking”

The Republican era also marks a period when the class boundaries of literature began to blur. Writers who lived in basements, struggled with landlords, and were constantly forced to move began to establish themselves on the literary scene. This shows that literature was no longer merely an expression of the privileged classes, but had become a means of expression for individuals engaged in the struggle for survival. In my view, the example of Orhan Pamuk is particularly striking in this context. The Pamuk Apartment in Nişantaşı and the writer’s texts recounting his own family history both reveal and question the relationship between literature and the upper classes. The class consciousness or distant narrative style that is sometimes felt in Pamuk’s language also reveals the echoes of the elitist codes that literature has carried from the past to the present. Ultimately, the neighborhoods that writers choose—or are forced to live in—are not merely physical locations, but also reflect their identities, aesthetic preferences, and ideological stances. A writer’s neighborhood is often a reflection of their worldview. Istanbul’s social geography also maps out the class structure of literature.

Which places stand out or are longed for in the texts of writers who describe an Istanbul that no longer exists?

Elements such as the recreational areas of old Istanbul (Çamlıca, Göksu, Bosphorus villas), mansion life, and neighborhood culture are often longed for. Similarly, in the Istanbul of various writers (such as Halide Edib), the solidarity and traditional way of life in the neighborhoods are described with a sense of loss. There is another point I would like to draw attention to. Nature, gardens, orchards, hillsides full of fruit trees, and production areas that nourish traditional culinary culture occupy an important place in Istanbul’s literature. These images, which describe both the daily life of the past and the city’s relationship with nature, are the memory of an Istanbul that has largely disappeared today. For this reason, such texts should be read not only as literary works but also as ecological and cultural documents.

“Memory Records of Lost Naturalness”

Gardens, orchards, and the products grown there—lettuce, figs, walnuts, artichokes, strawberries, etc.—reflect Istanbul’s old rhythm, intertwined with nature. These spaces are also the sources that define the city’s cuisine, its scent, and its rituals. These narratives show that Istanbul is not just about stone and sea; it is also a city that produces, smells, blooms, and lives according to the seasons. In the past, every neighborhood had its own garden or orchard. Langa, Yedikule, Salacak, Kuzguncuk gardens… These areas nourished both the city’s cuisine and its social fabric. Now, most of them have either been destroyed or reduced to mere “landscapes,” severing their connection to production.

Thus, these literary works serve as memory records of a lost naturalness. They can also be read as a silent protest against today’s urbanization, the commodification of land, and the transformation of public green spaces into commercial spaces.

What has replaced the spaces that no longer exist today? How do you respond to this transformation?

Unfortunately, many literary spaces have been turned into shopping malls, parking lots, concrete blocks, or faceless buildings. This transformation brings with it not only physical change but also the erasure of social memory. The loss of a space’s spirit means the drying up of the veins that nourish literature. That’s why I respond to this transformation process critically, questioningly, even angrily. Before Narmanlı Han was restored, I would look through the window at Tanpınar’s room, sit by the wall in the quiet garden, and think about what Tanpınar had written. Aliye Berger, Ferit Edgü’s Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu gallery… Narmanlı Han, which has been transformed into a crazy eating, drinking, and entertainment venue without any attention to preserving these things and passing them on to future generations, now pains me, and I turn my head away when I pass by. Yet during its restoration process, people kept saying things like, “In Europe, this is how it is, in Europe, that is how it is.” In Paris, such a building with such a courtyard would not be sacrificed to such an insatiable appetite.

What message should the Istanbul Literature Map convey to future generations, and what should readers take away from this work?

The most important message that the Istanbul Literary Map should convey to future generations is that cities are not only physical but also emotional, intellectual, and cultural layers. Understanding a city requires not only walking its streets but also knowing who walks those streets, what they look at, what they feel, and what sentences they form. This work explores ways of thinking of Istanbul as more than a geographical space, but as a literary memory space.

In many European cities—such as Paris, Berlin, or Prague—we see small plaques on the walls of the houses where writers lived, the cafes where they sat, and the streets where they wrote. Simple yet eloquent signs like “Rainer Maria Rilke lived here” or “Sartre wrote at this table”… These signs do not merely evoke a memory; they reveal the will that transforms a city into a space of memory.

Unfortunately, this kind of culture of preservation and visibility is quite weak in Istanbul. Yet this city also has its own Rilkes, its own Woolfs, its own Borges. The streets Tanpınar walked, the Bosphorus Yahya Kemal gazed upon, the outlying neighborhoods of Osman Cemal Kaygılı—these are not merely individual memories but carriers of collective memory. If a society forgets or ignores its writers, the places where they lived, wrote, and thought, it will eventually begin to forget itself. Because a city is not only the sum of today, but also of the past and the future. This map is an effort to carry the traces of the past into today’s perspective and pass them on to the future.

“Remember, the place you live is a time.”

When future generations look at this map, they should realize that the city is not just a collection of concrete and asphalt. Every corner hides a story, every window a poem, every door a novel. And a city lives and makes sense of itself to the extent that it speaks through literature. Preserving Istanbul’s literary memory is, in fact, preserving Istanbul itself. The most important thing for the reader is that places also have a memory, and this memory can be kept alive through literature. “Remember, the place you live is a time. There is a poem, a novel, a story hidden in the street you walk on. You just have to know how to look.”