The restoration of the Selimiye Mosque, Mimar Sinan’s masterpiece, has shifted from a scientific conservation project into an ideological confrontation. Despite the years-long meticulous work approved by the Scientific Board, an attempt by a group calling itself the “Selimiye Mosque Inspection and Investigation Committee” to “remove” baroque ornamentation has triggered both a cultural and legal crisis. Today, Selimiye stands not only at the center of a dispute over a dome, but also of the question: to whom does cultural heritage belong?

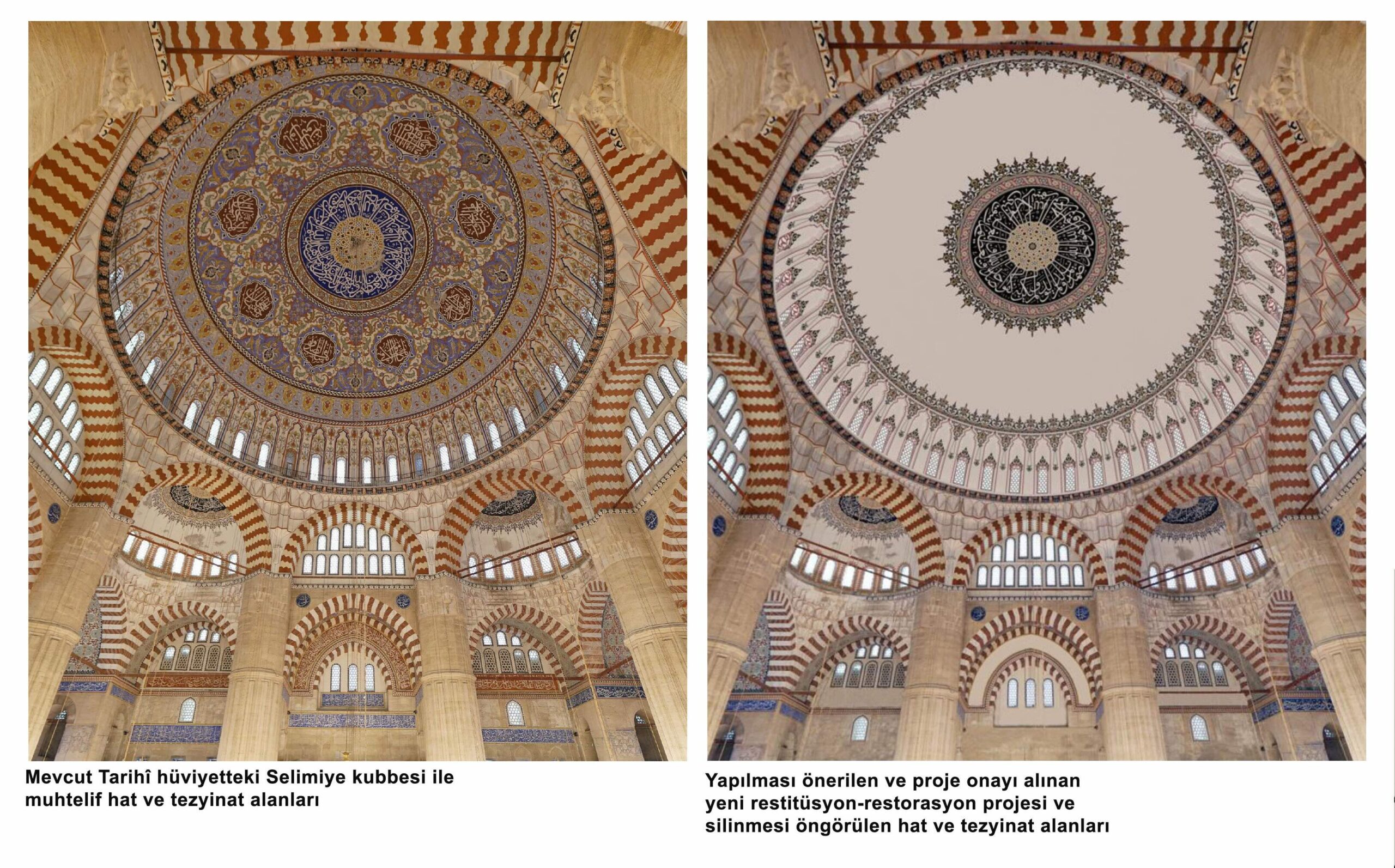

In the restoration of the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne, inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List and Mimar Sinan’s crowning work, which began in 2021, ornamental paintings, calligraphy and decorative work were carried out meticulously under the supervision of the Scientific Board and in line with scientific data, historical documents, and original examples, and overseen by the General Directorate of Foundations. The restoration of the main dome began on June 19, 2023, with the approval of the Edirne Regional Board for the Conservation of Cultural Properties, and was completed in December 2024. However, a group calling itself the “Selimiye Mosque Inspection and Investigation Committee” intervened in the process. Claiming that the current state of the dome did not reflect Mimar Sinan’s decorative approach and that baroque-influenced embellishments had been added during later repairs, the committee attempted to impose its own project. Moreover, beyond the ornamentation of the main dome, they proposed scraping and destroying the decorations in the prayer hall, the semi-domes, and the mihrab area, replacing them with a project almost entirely covered in plain white plaster, soulless and devoid of originality.

The same committee presented its project to the Scientific Board in February 2024, after obtaining authorization on September 29, 2023. The project was rejected on the grounds that “sufficient documentation and scientific data were not provided.” It was then submitted to the Edirne Regional Board for the Conservation of Cultural Properties in May 2024 and rejected again. Subsequent appeals in January and June 2025 sought to cancel the approval of the completed restoration, but were once more rejected by the Conservation Board. The project, which had already been rejected three times, was finally accepted by the Edirne Regional Board for the Conservation of Cultural Properties on July 29, 2025. Meanwhile, the issue was aggressively carried into the public sphere and caused great uproar on social media. The Edirne Administrative Court, responding to widespread debate and individual legal efforts, halted the Selimiye Mosque dome restoration on September 27, 2025, on the grounds that the project “may cause irreparable damage to the historical structure.” The court demanded all documents and approved visuals relating to previous restorations at Selimiye. It also requested clarification on whether a scientific report had been prepared during the current project. A 30-day defense period was granted, and the court stated that its final decision would be based on the collected information and documents.

On the right: The newly proposed restitution–restoration project, for which approval has been granted, and the calligraphy and ornamentation areas that are planned to be removed.

Non-Baroque Ornamentation

Before the suspension ruling, according to a special report published by Anadolu Agency on September 20, 2025, the main issue troubling the committee was the supposedly baroque ornamentation added to the dome in the 1800s. The committee’s chairman, Uğur Derman, told AA:

“It deeply disturbs me that Selimiye Mosque was filled, at the beginning of the 19th century, by local writers, people who cannot even be called calligraphers. I hope these are removed as soon as possible.”

The committee’s vice-chair, Prof. Dr. Saadettin Ökten, criticized the baroque decoration as follows:

“He writes a verse inside a medallion, but there is a medallion. So from the perspective of civilization, baroque is foreign to me, something that repels me. Baroque ornamentation carries you away, to where? To superficiality. Any element that does not lead to tawhid and sunnah must be removed from there with propriety.”

Ökten’s phrase “removed with propriety” clearly implies covering it with lime.

Miniature painter and architect Semih İrteş stated:

“It is everyone’s desire that this building returns to its authentic identity,”

while calligrapher Mehmet Özçay asserted:

“The revival of these inscriptions, which are neither original nor of historical or artistic value, is utterly wrong. They must be removed.”

In summary, although the restoration decisions were based on a scientific and professional study prepared by the Scientific Board members, Prof. Dr. Baha Tanman, Prof. Dr. Can Binan, Dr. Ali Rıza Özcan, Prof. Dr. Fevziye Aköz, and Prof Dr. Alper İlki, drawing on historical documents, reference works, academic studies, scraping data, and charters outlining restoration principles, an intervention devoid of scientific basis was imposed by a group deriving its legitimacy from ideological concerns. Prof. Dr. Baha Tanman, who played an active role in preparing the evaluation report rejecting the project, stated that he stood by his opinion and agreed entirely with the views of Prof. Dr. Zeynep Ahunbay. Dr. Ali Rıza Özcan declared that although the restoration was completed and approved by the Scientific Board, he opposed the acceptance of this restitution project. Prof. Dr. Can Binan, who had served on the Scientific Board since the beginning of the restoration, resigned in protest after the board’s evaluations were disregarded.

Ortaylı: Sinan’s Works Are Not a Heritage to Be Consumed by Every Individual or Society

It appears that the Selimiye Mosque faces the danger of being dissolved under the weight of interest groups and personal ideological preferences. This issue could set a precedent for future restoration projects and demonstrates that interventions regarding history and cultural heritage are no longer merely technical matters. İlber Ortaylı criticized the initiative in a striking Instagram post on September 9, 2025, asking whether this was “a cultural revival or destruction?” and adding:

“There is clearly the smell of group collaboration here. Anyone with naked eyes can see the difference of taste between the old structure and the new. Apparently, this business is either being decided incompetently or through favoritism.”

In another post on September 30, 2025, Ortaylı added:

“Our laws, especially UNESCO’s rules, and strict conditions are clear. If you imagine doing this without obtaining permission—by forcing it through—you are making a grave mistake. Mimar Sinan is the genius who gave his own style and central Ottoman spirit to the imperial geography and the empire’s art. Let everyone learn to protect 16th-century Turkish architecture and the great master’s greatest work. You have not even determined the history of the calligraphy and ornamentation you dislike. You enter restoration with a baseless judgment, actually, you already have. Sinan’s works are not a heritage every individual, nor every society, can monopolize and squander.”

As Ortaylı’s reference to “UNESCO’s rules” indicates, the debate exceeds national boundaries. The International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) Turkey National Committee, in its official opinion dated June 11, 2025, stated that the imposed project violated the Venice Charter, the Nara Document on Authenticity, the Burra Charter, the UNESCO World Heritage Operational Guidelines, the ICOMOS Turkey Declaration on the Conservation of Architectural Heritage, and Turkey’s Principle Decision No. 660 of the High Council for Conservation. It also decisively refuted claims of baroque influence on the Selimiye dome. According to ICOMOS Turkey, the existing decorations do not deviate from Sinan’s style, and the alleged baroque effect does not threaten the mosque’s historical and cultural integrity. Moreover, ICOMOS warned that potential interventions could pose serious risks not only to the artistic and historical value of the monument, but also to its UNESCO World Heritage status. In short, every alteration directly endangers Selimiye Mosque’s internationally recognized heritage status.

A Deep Socio-Political Crisis

Although the restitution project for the Selimiye Mosque has been halted by a court order, the legal process has not reached a definitive conclusion. Therefore, the gravity of the situation has not yet diminished. The motivations behind the new project opposed by the Scientific Board and the public remain unclear. At the technical level, questions persist regarding whether Sinan’s style was preserved in previous restorations, or how layers belonging to Sinan’s period were evaluated. However, the issue goes beyond these technical matters, pointing to a deep socio-political crisis in which cultural heritage is shaped by ideological preferences rather than scientific principles.

The resulting picture, corruption, questions of competence, monopolization of restoration tenders, the involvement of non-experts, and decisions on which historical layer to preserve or erase being made without regard for the Scientific Board’s statements and reports, opens the door to cultural heritage becoming an instrument for legitimizing political power. The suspicion that cultural heritage is a field shaped by epistemic communities, groups of experts who legitimize their own values and interests under the guise of “truth”, according to political and ideological inclinations, now occupies our minds more strongly, and it is impossible to escape this suspicion.

The restoration of the Selimiye Mosque, Mimar Sinan’s masterpiece, has shifted from a scientific conservation project into an ideological confrontation. Despite the years-long meticulous work approved by the Scientific Board, an attempt by a group calling itself the “Selimiye Mosque Inspection and Investigation Committee” to “remove” baroque ornamentation has triggered both a cultural and legal crisis. Today, Selimiye stands not only at the center of a dispute over a dome, but also of the question: to whom does cultural heritage belong?

In the restoration of the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne, inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List and Mimar Sinan’s crowning work, which began in 2021, ornamental paintings, calligraphy and decorative work were carried out meticulously under the supervision of the Scientific Board and in line with scientific data, historical documents, and original examples, and overseen by the General Directorate of Foundations. The restoration of the main dome began on June 19, 2023, with the approval of the Edirne Regional Board for the Conservation of Cultural Properties, and was completed in December 2024. However, a group calling itself the “Selimiye Mosque Inspection and Investigation Committee” intervened in the process. Claiming that the current state of the dome did not reflect Mimar Sinan’s decorative approach and that baroque-influenced embellishments had been added during later repairs, the committee attempted to impose its own project. Moreover, beyond the ornamentation of the main dome, they proposed scraping and destroying the decorations in the prayer hall, the semi-domes, and the mihrab area, replacing them with a project almost entirely covered in plain white plaster, soulless and devoid of originality.

The same committee presented its project to the Scientific Board in February 2024, after obtaining authorization on September 29, 2023. The project was rejected on the grounds that “sufficient documentation and scientific data were not provided.” It was then submitted to the Edirne Regional Board for the Conservation of Cultural Properties in May 2024 and rejected again. Subsequent appeals in January and June 2025 sought to cancel the approval of the completed restoration, but were once more rejected by the Conservation Board. The project, which had already been rejected three times, was finally accepted by the Edirne Regional Board for the Conservation of Cultural Properties on July 29, 2025. Meanwhile, the issue was aggressively carried into the public sphere and caused great uproar on social media. The Edirne Administrative Court, responding to widespread debate and individual legal efforts, halted the Selimiye Mosque dome restoration on September 27, 2025, on the grounds that the project “may cause irreparable damage to the historical structure.” The court demanded all documents and approved visuals relating to previous restorations at Selimiye. It also requested clarification on whether a scientific report had been prepared during the current project. A 30-day defense period was granted, and the court stated that its final decision would be based on the collected information and documents.

“It Would Be a Great Mistake to Take This Restoration as a Basis”

Prof. Dr. Gülru Necipoğlu – Harvard University, Department of History

It is impossible for me to take seriously the alternative restoration project proposed for the dome ornamentation of the Selimiye Mosque. Such a dome decoration, comprised solely of calligraphy in black, white, and gray tones, with the rest consisting of an entirely empty white background, stands in stark contrast to Selimiye’s vivid color harmony and Mimar Sinan’s aesthetic sensibility. For example, the colorful, intricately patterned İznik tiles in the mosque’s mihrab and royal lodge; the colorful painted ornamentation of the muezzin’s platform directly beneath the dome; and furthermore, Selimiye’s widely known old museum-quality carpets with multicolored floral patterns… In my opinion, the colorless and excessively plain dome decoration now proposed for restoration may well be an old draft that was once attempted but abandoned because it was not liked. The period and date of its production are also unknown. To take this as the basis for restoration would be a great mistake. The fact that it has caused so much resonance is itself surprising. I believe Mimar Sinan would think the same way. Unfortunately, since I had to teach as a professor at Harvard University’s Department of Art and Architectural History this academic year, I could not examine the restoration and the dome from inside the mosque. However, the published photographs are sufficient to support the view I expressed above.

“Very Grave”

Prof. Dr. Süha Özkan – Architect, Architectural Historian, Theorist

There is an international Venice Charter (1964) that sets out all the rules regarding restoration and modification. It clearly states: you can use technology solely for the purpose of preservation; you cannot alter anything by intervening in its original form. This is a very clear and globally accepted norm. Any intervention contrary to this is not only wrong but also morally unacceptable. They are not even aware of how grave this matter is. Therefore, the only thing that can be done in such a situation is to evaluate such an attempt within the scope of a scientific study.

“Cultural Heritage Is Becoming a Battleground”

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ali Yaycıoğlu – Stanford University, Department of History

There are major and interesting points of crisis in Turkey. We constantly witness cultural wars erupting from various places. Instead of embracing a shared heritage critically, every aspect of it, in every field and from every period, everyone glorifies their own favored era, aesthetic, or figures without questioning them. Society cannot construct a shared historical narrative. As a result, cultural heritage turns into a field of struggle, a battleground.

We construct the past on refutation. We attempt to revive one period while rejecting another. For example, we reject one layer and try to build an identity solely through the Sinan period or the so-called “Golden Age.” Yet buildings are living entities. For instance, Selimiye has its own 450-year history. A structure does not remain static as it stands; it lives, transforms, and accumulates memory. But you reject all this lived experience and try to freeze yourself in the 16th century. This is very strange.

Reading history through a single “origin” is a grave mistake. History is a process; it must be read through continuity. What we see here, however, is an obsession with origin and an attitude that ignores all lived experience. There is a fallacy involved: by saying “Sinan would have done it like this,” a pure, singular “Sinan style” is invented. The search for an origin is a type of salafi attitude and rejects historical plurality. Yet history requires pluralism; we must look at the past plurally and understand its layers in a pluralistic manner.

What we call “originism” leads us toward an iconoclastic place. What is intended in Selimiye is, in fact, a type of cultural iconoclasm: an attempt to reconstruct cultural hegemony by erasing the past. Different powers have done this before—we saw it among Kemalists as well. But this method does not work. Because nothing that ignores lived experience, society, or life can truly survive.

“There Is an Ideological Approach”

Prof. Dr. Ali Uzay Peker – Middle East Technical University, Department of Architecture

Behind this imposed project lies an ideological approach. Yet these discussions are issues long surpassed in the fields of art and architectural historiography. In the 1970s, some scholars interpreted Ottoman Baroque as a result of Westernization and degeneration. However, later research revealed that this style was an expression of a changing society. The Ottoman dynasty was always inclined toward what was global and contemporary. Mimar Sinan employed the decorative style of the 16th century, not the 14th or 15th.

The problem stems from an effort to “purify” history and its works, as if the Ottoman state of the 16th or 17th century were frozen in time and had to be preserved unchanged. Yet history has changed; the Ottoman world changed and transformed. Some still live in a fictional world fueled by the dream of a “Golden Age,” seeking a flawless Ottoman and pure Sinan style.

As we see in other restoration examples, there may also be different agendas behind such approaches: material interests or the desire to leave one’s signature, for instance. However, such baseless and irreversible interventions are wrong and unforgivable. Ultimately, this issue is not merely a technical restoration debate; it is also a matter of cultural attitude. Ideological approaches, material and spiritual preferences, and practices by certain influential circles can damage historical cultural heritage. Therefore, we must remain vigilant against such attempts and defend conservation approaches that respect historical layers and rely on expertise and scientific foundations.

“Restoration Is a Scientific Activity”

Prof. Dr. Zeynep Ahunbay – Istanbul Technical University, Department of Architecture

In the contemporary world, restoration is a scientific activity and is carried out according to international conservation principles. A cultural asset is a living organism; it is maintained through repairs over time. These repairs constitute part of the Selimiye Mosque’s past and carry documentary historical value. The existing decorations on the mosque’s dome are remnants of late Ottoman restoration work and represent artistic contributions reflecting the aesthetic understanding of the period and should be preserved.

The justification for covering existing traces and decorations is that they do not correspond to the 16th-century structure. This is a subjective interpretation. If, during research, a well-preserved layer from the original construction period had been found beneath the existing decoration, the matter could be discussed and an appropriate method of presentation sought. However, traces from the 16th century are limited, and applying a decorative project developed with insufficient data to a World Heritage monument is against conservation principles. For this reason, architects and other conservation experts strongly oppose the project.

Moreover, the presence of late Ottoman decorations in any classical-period Ottoman mosque is not unique to Selimiye. Many early and classical Ottoman mosques were repaired in the 19th century; their interiors were adorned with late Ottoman calligraphy and painted ornamentation. During contemporary restorations, research is conducted beneath upper decorative layers to determine whether original data exists. During the restoration of the Süleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul, traces from the 16th century were sought beneath the existing 19th-century decorations; however, due to insufficient data, the later decorations were preserved.

“There Is a Serious Risk of Loss”

Dr. Gülsün Tanyeli – Istanbul Technical University, Department of Architecture

There is a serious risk of loss at Selimiye. It is unacceptable that a structure we proposed for and had accepted onto the World Heritage List—and to which we pledged to “not touch even a single hair”—is now on the agenda in this manner. Furthermore, disregarding the Scientific Board and interfering with such an important heritage is extremely dangerous. The issue is not limited solely to scientific or technical aspects; there is also an economic dimension. Subjecting an already completed restoration to a second project raises enormous questions. Where did this need arise? Who will bear the financial burden of this decision? To whom will the financial responsibility be attributed tomorrow?

The fact that many experts in cultural heritage, architectural history, and restoration remain silent does not mean they approve; they know full well that this should not happen. The fact that everyone opposes it for different theoretical, technical, or economic reasons is evidence of this. It must be remembered that such decisions shape the future. Just as decisions taken during the Menderes era for demolitions and road construction in Istanbul are now recalled as negative precedents, so too will a wrong decision about Selimiye be remembered negatively.

“The Right Thing to Do Is What the Scientific Board Says”

Dr. Evrim Binbaş – University of Bonn, Department of History

This issue is not simple; behind it lies a serious intellectual illusion. It is connected to the evolution of debates on history and civilization in Turkey over the last 30 years. Since the 1990s, the concept of “civilization” has gained importance both globally and in Turkey. Empires such as the Ottoman Empire began to be discussed within a broader civilizational framework; the “Alliance of Civilizations” projects of the early 2000s were products of this approach. But after 2016, the direction changed. The Ottoman civilization, once conceptualized in close relation with Western civilization, was detached from the West and reimagined as a “self-contained whole, free from external influences.” The origins of this understanding actually go back to the 18th century: civilization is corrupted by external influences and must be restored to its “authentic” form.

The Selimiye restoration debate reflects precisely this idea. The “Selimiye Mosque Inspection and Investigation Committee” claims that the structure belongs to a pure Islamic civilization and was later corrupted by external influences such as the baroque.

This poses several problems: First, the Ottomans who restored Sinan’s works in the 18th and 19th centuries were also Ottomans. Which Ottomans will we consider “correct”? To revert a work to an assumed original state through arbitrary decisions is methodologically and morally problematic. Second, civilization is conceptualized as a pure whole free of internal contradictions. Yet every civilization in history contains both strengths and contradictions. This narrowing and exclusionary understanding of civilization misdirects restoration decisions.

Perhaps the Selimiye debate will be beneficial. This issue has brought everyone together, from Islamists to secularists, from the right to the left. If this situation forces us to question the concept of civilization again, so much the better. Regarding restoration, the correct approach is to do what the Scientific Board says.

“Is Some of History Heritage, and Some Not?”

Prof. Dr. Agah Tarkan Okçuoğlu – Istanbul University, Department of Art History

Anyone engaged with the historiography of Turkish art and architectural history recognizes the problematic aspects of many writings on the modernization process. Many people still struggle to accept the art produced in the Ottoman lands during the 18th and 19th centuries as genuine artistic production. Therefore, the 18th-century painted decorations on the dome of the Selimiye Mosque are disliked by some, perceived as harmful to “national sensitivities” by others, and provoke discomfort regarding certain phases of the mosque’s 450-year decorative history.

Is the purpose of restoration to revive a period chosen according to personal preference without documentary basis? Is part of history heritage and part of it not? Can you propose a fictional calligraphic program simply because you do not like the calligrapher who decorated the dome in the 18th century? Of course not! The fundamental aim of the discipline of restoration is not to arbitrarily rebuild a structure according to any era, but to preserve the historical integrity of the building. For this reason, the conservation and restoration of historical structures must be carried out independently of personal tastes or ideological concerns, within the framework of universal scientific criteria and national/international legal regulations.