Across Turkey, olive groves are no longer just agricultural lands—they have become battlegrounds, moral tests. A society that fails this test does not merely lose its natural environment, but also its cultural continuity. When an olive tree is cut down, it is not only a tree that is silenced—it is the voice of a people, the abundance of a table, the conscience of a nation.

The olive tree is not merely a plant of the Mediterranean; it is a living being rooted in the shared conscience of humanity, speaking the language of the earth’s memory. It is the bearer of peace, the teacher of patience, the symbol of rootedness. Every curve, every notch on its trunk is like a page from a millennia-old ledger of time. It is silent—but never voiceless. Its trunk tells of the past, its branches of the future. Human memory may falter, but the olive tree does not forget—neither floods, nor wars, nor droughts, nor betrayal. That is why not only people, but entire civilizations have found rest in its shade.

The Vouves tree in Crete is between 4,000 and 5,000 years old and still bears fruit. Each year, thousands of people travel to Crete to witness this living memory. In Italy, the “Millenari di Puglia” initiative documents and protects ancient olive trees, recognizing them not only as carriers of the past but as guarantors of genetic diversity and cultural continuity for the future.

The Millennia-Long Companionship Between Humans and the Olive Tree

The relationship between humans and olive trees goes far beyond domestication. First cultivated in Anatolia, the olive tree has accompanied humanity from Mesopotamia to Crete, Greece to Rome, Andalusia to Latin America. As humans embraced the olive, war transformed into peace, and darkness gave way to light. For the olive represents more than fruit—it is a material and spiritual symbol of peace, shade, light, and coexistence.

In Catalonia, Spain, the Farga d’Arió tree, measured by laser perimeter technology, is dated to the year 314 CE, during the reign of Roman Emperor Constantine. In Crete, the Vouves tree—between 4,000 and 5,000 years old—still bears fruit. In Italy, the “Millenari di Puglia” initiative has catalogued and protected countless millennia-old olive trees. These are not only remnants of the past, but seeds of the future.

Olive Trees in Literature, Art, and Resistance

In Homer’s Odyssey, the bed symbolizing Odysseus’s return and marital fidelity is carved from an olive tree. In Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, the olive tree represents cyclical time and family memory. In the poetry of Pablo Neruda, the olive tree becomes a metaphor for labor, peasantry, and connection to the land.

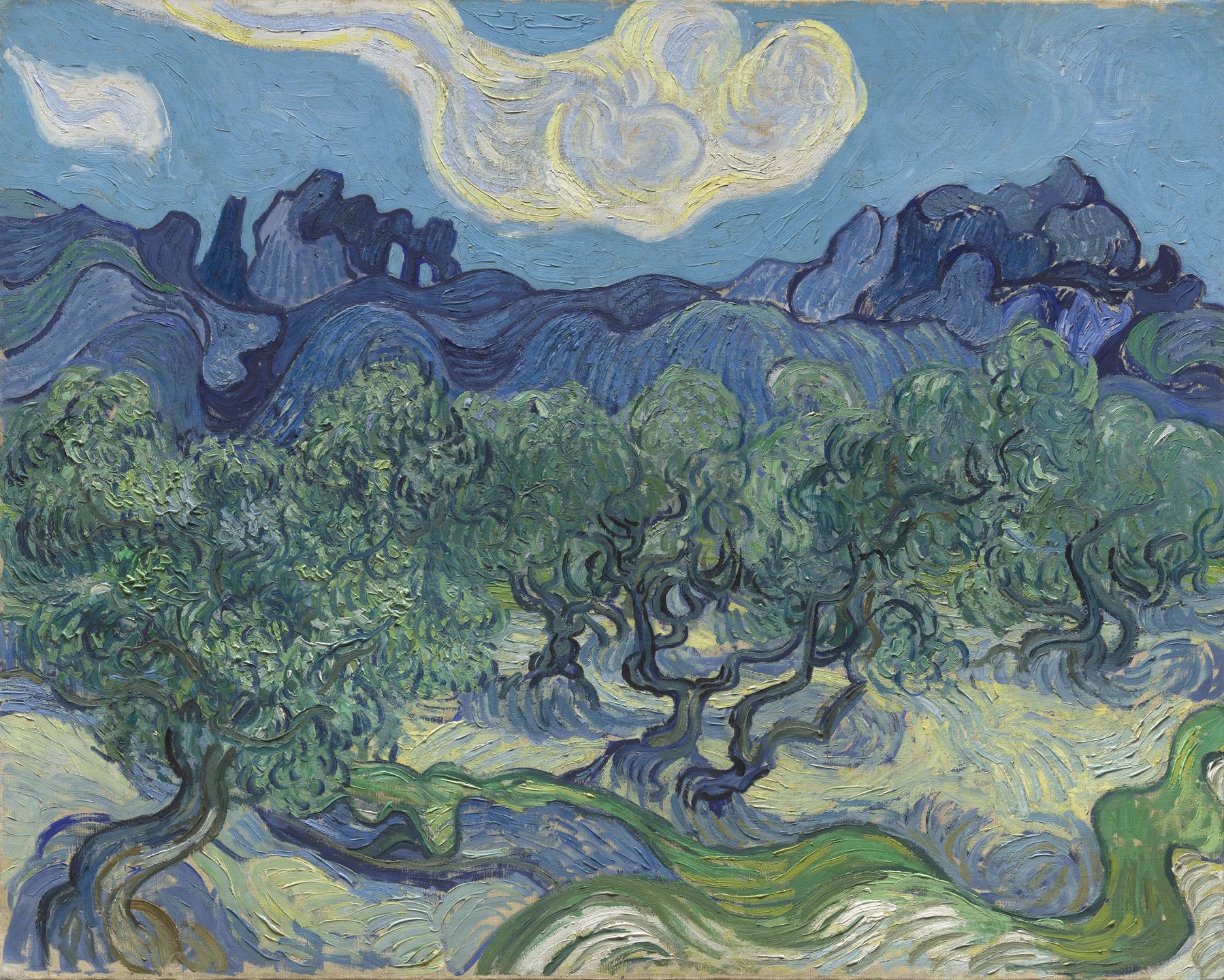

In art, the olive tree is not merely a formal motif—it often symbolizes inner turmoil. The olive trees painted by Vincent van Gogh in the countryside of Provence reflect his spiritual communion with nature and the divine. Picasso’s dove carrying an olive branch, drawn in 1949 for the World Peace Congress, became a global symbol of the yearning for peace after World War II.

For Palestinian artists, the olive tree represents longing—for land, for home, for memory. In every cut, trunk, and figure, one sees roots standing against displacement. Here, the olive tree is not merely a plant but a site of memory in resistance to exile.

Turkey’s Test with the Olive Tree

The Olive Cultivation and Grafting Law (Law No. 3573), enacted in 1939, was the Republic of Turkey’s first major promise to the olive. This law strictly prohibited the reduction, destruction, or repurposing of olive groves. To cut down an olive tree, ministerial approval was required, and construction was limited to 10% of the land. It was not merely an environmental regulation—it was a cultural pact. After all, the olive is a pillar of Turkey’s agriculture, an essential element of its cultural identity and local economy.

Today, however, these protections have been eroded by “omnibus laws.” Though still protected on paper, olive trees are quietly being eliminated in practice. Regulatory changes concerning olive groves are often buried within unrelated legislation. Agricultural land is increasingly being reclassified for non-agricultural use under the guise of energy needs, reconstruction after disasters, or development. Exceptions are now becoming the rule.

6,000 Olive Trees Cut in a Single Night

In 2013, 6,000 olive trees were cut overnight in the village of Yırca, Soma, to make way for a coal-fired power plant. The fields were fenced off. Villagers defended their trees with their bodies through the night. The olive was not just a source of income—it was the voice of the land, the heart of the family table, a promise to the future. The trees felled that day in Yırca were not just trees; they were lives, memories, and a people.

This event brought the destruction of olive groves into public consciousness for the first time on a large scale in Turkey. But since Yırca, much has changed—and yet nothing has. Omnibus laws continue to target olives. Circumventing the law has become easier. “It’s for energy,” they say. “It will bring investment,” they claim. Yet the olive tree itself is an investment—one in rural production, in cooperatives, in subsistence economies.

From Yırca to Hatay

Following the devastating earthquakes in Hatay in 2023, 321 acres of olive groves were rezoned for construction in the newly declared disaster area. This decision ignored the olive tree—the region’s most ancient companion in survival—at a moment when life sought to rise from the rubble.

Later that year, another bill passed in parliament opened olive groves to mining operations. Companies are now uprooting these ancient trees under the pretext of electricity generation. And the public is misled with promises that the trees will be “relocated.”

“The Olive Tree Cannot Be Moved”

Experts are clear: olive trees cannot be relocated. Even if moved, it takes 5 to 10 years to return to former productivity—if they survive at all. Most are left to wither. Olive trees must live where they are born. They are inseparable from their soil, trunk, and roots. Prof. Dr. Mücahit Taha Özkaya states that this process is neither economically nor ecologically sustainable. Prof. Dr. Doğan Kantarcı puts it more bluntly: “A transplanted olive tree won’t survive. And even if it does, the villagers will starve.”

“We Are Farmers, We Are Right, We Will Win”

Farmers from İkizköy, a village in Muğla’s Milas district, are resisting the omnibus bill that would open olive groves to mining:

“We are the farmers who sustain this country. We will escalate our resistance to the omnibus bill pushed through parliamentary commissions by force, against our will. Let there be no doubt: we haven’t said our last word yet! From ages 7 to 70—we are in resistance! We are farmers, we are right, and we will win!”

When an Olive Tree Is Cut Down…

When the olive tree is cut down, what is left for us to hold on to?

To peace? To shade? To labor? To our roots? Or only to regret?

When the olive tree is cut, it is not only the soil that dies—we wither, too. Olive groves across Turkey are no longer just fields; they are battlegrounds, moral questions. A society that fails to answer this question loses not only its nature, but also its cultural continuity.

When the olive tree is felled, it is not just a tree that is silenced—it is the voice of a people, the abundance of a table, and the conscience of a nation.

It is not law that protects the olive tree—it is conscience.