From ancient mythologies to modern narratives, many powerful women have been “demonized” by society’s fears and prejudices. In myths, women are often either “sacred mother” or the “destructive witch”. Obedient motherhood and traditional families are idealized, while rebellion, sexuality, and freedom are vilified. These stories actually a product of a patriarchal view. Women should be beautiful, obedient and fertile. For centuries, some figures have been labeled as threats, when in truth they mirror patriarchy’s own fears. These vilified female figures are used to shape society by scaring people with telling them terrifying stories, writing books about vilified women, or even making artworks to show people how horrifying it is to be a “bad” woman.

Across visual culture, we can trace how art has helped to construct and reinforce these very stereotypes.Women’s bodies and powers have repeatedly been framed as either divine or dangerous. Whether in Europe, the Middle East, or East Asia, different civilizations produced myths in which women’s strength became a source of fear. Art, therefore, not only reflected patriarchal ideology but actively participated in shaping it: by aestheticizing control, by moralizing beauty, and by transforming powerful women into cautionary icons that warned others about what happens when a woman becomes too free or powerful.

Lilith: The First Rebellious Woman

According to mythical texts, Lilith was created with Adam as first humans before Eve. She claimed that she and Adam were equals and refused to submit to him.This story has several versions. In one of them she rejects lying beneath Adam during sex and it was against the fixed hierarchy. For this disobedience, she is expelled from (or chooses to leave by her own will) Eden. Just because she refused to submit to a man patriarchy made her an a “night demon,” and blamed for killing infants and seducing men. These fearful traits reveal how a free, non-compliant woman was turned into a monster by the male imagination. After her god made Eve from Adm’s rib so she had to obey to Adam and she became the symbol of an “acceptable,” obedient woman.

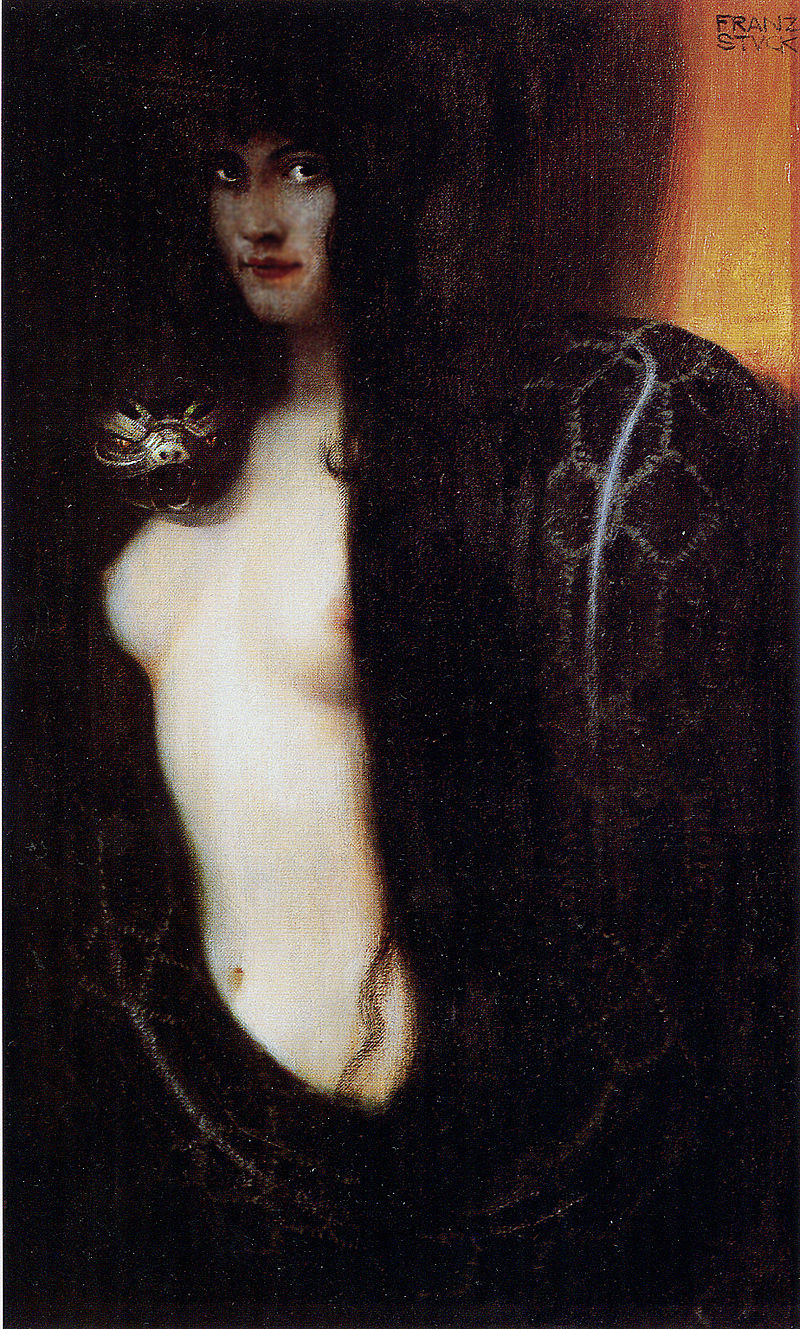

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s painting “Lady Lilith” portrays Adam’s legendary first wife as a woman captivated by her own beauty. By showing Lilith brushing her hair and gazing into a mirror, Rossetti turns her into a 19th-century femme fatale using the Pre-Raphaelite taste for vivid color and mythic references. Here, Lilith is not a demon but a powerfulfigure. The mirror behind her is a a symbol Rosetti uses. It is a symbol of self-awareness and maybe narcissism. Unlike classical representations of her, here the mirror is her control and power. Lilith’s gaze is inward, detached from the viewer, refusing the “male gaze.”

Across art and literature, Lilith’s image has shifted with the times. In the Middle Ages and Renaissance, she often appears as a female tempter who leads Adam astray. In the 19th century, especially among the Pre-Raphaelites, artists “rediscovered” her. Works like Rossetti’s “Lady Lilith” show her with long hair and a confident pose and by that Lilith became the symbol of independence and power. Today, Lilith is counted as the first woman who rebelled and feminists are standing with her. Once she was demonised and now she is not alone with her stance.

Medusa: Beauty Turned into a Monster

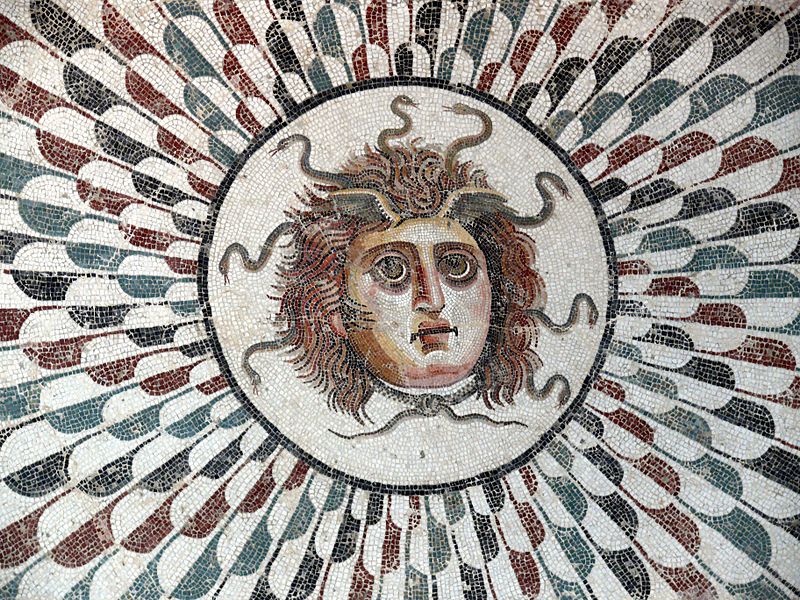

Medusa is known as the snake-haired monster who could turn people to stone with a single glance. She might be one of the most tragic figures of ancient Greek mythology. Behind her terrifying stories there lies a story filled with injustice and patriarchy. Medusa actually was a beautiful mortal woman and she got raped by the sea god Poseidon in Athena’s temple. But the punishment goes to an innocent oman rather than a powerful man, Poseidon. Athena got so angry when her virgin temple has been desacreted, she punished Medusa by turning her hair into snakes and making her not beautiful anymore. This myth clearly reflects a system that even blames rape on the woman. Medusa’s punishment is among the earliest examples of how patriarchy turns the “seductive woman” into a monster.

Medusa’s story does not end there. The task of killing her is assigned to the hero Perseus. With the gods’ help likenAthena’s polished shield, Hermes’s curved sword, and Hades’s helmet of invisibility, Perseus catches Medusa off guard as she sleeps and beheads her. In other words, even goddesses and gods collaborate to secure a male victory. Medusa’s story is basically telling that her only “crime” was her being beautiful. According to the legend, Medusa is so beautiful that it is assumed she seduced Poseidon

In Benvenuto Cellini’s famous sculpture, Perseus raises Medusa’s severed head in triumph, presenting her as the defeated monster. This work stands as one of the technical and ideological peaks of Renaissance sculpture. The hero’s muscular, idealized body reflects a “heroic anatomy” similar to Michelangelo’s David. Cellini uses bronze not merely as a material but as a dramatic medium: the polished surface captures light, accentuating Perseus’s divine triumph. From a feminist perspective, however, this victory also embodies the silencing of the female gaze. The sculpture, while celebrating the humanist ideals of the Renaissance, simultaneously materializes a patriarchal display of power.

In recent years, Medusa has become a significant symbol of the feminist movement: especially during the #MeToo era, she has been reborn as an icon representing the rage and resilience of survivors of sexual violence. Many women have even chosen Medusa tattoos as emblems of their survival.

Witches: When Fear Became Witch-Hunts

Witches are perhaps the most real example of women demonized just because men thought they are too powerful for a woman throughout history. While other stories are rooted in myth, the days when these women were called witches and burned alive were not tales, they were reality. As Europe moved from the Middle Ages into the Early Modern period, thousands of women were burned or hanged under accusations of “witchcraft”.. From the late 15th century through the 18th century, witch hunt trials especially targeted midwives, female healers, widows, and independent women living alone. Women can be accused simply for delivering babies or healing people with herbs or being codependent .

These killings didn’t actually just happened in the Middle Ages but got worse after the Renaissance. When old religious ideas weakened and the Catholic Church lost its power, the Inquisition used fear and superstition to control people by accusing and burning thousands as witches. In short, men justified their fear by accusing and punishing women by calling them witches.

In art history, the witch figure becomes visible from the Renaissance onward. German printmaker Albrecht Dürer’s famous early-1500s engraving often titled “Witch Riding Backwards on a Goat” is widely seen as laying down the template for later witch imagery. In it, Dürer depicts an old, ugly, long and hooked nosed, naked woman riding a goat which is a symbol of the devil backwards, with a broom in her hand and fallen angelic figures at her feet. Despite facing into the wind, not a single strand of her hair seems disturbed, making her appear powerful since its against humanity. With the Dürer’s work classic witch stereotype becomes a thing.

Painter Francisco Goya explored the theme of witches in the late 18th century in works like “Witches’ Sabbath” and “Witches in Flight.” While referencing the myths of his time, he also criticized this culture of fear. In Goya’s paintings, the devil often appears in goat form and the ugly, aged witches gathered around him. In this period’s art, witches are usually portrayed flying, doing rituals, or sacrificing children. The witch hunt is actually a result of a panic over women who are strong and independent and cannot be easily controlled. Today, when we look more closely at the “witch” image, we see that many of these women were simply the knowledgeable, or not suitable for the ideals they were expecting from women of their day. Today, people, especially women, continue to learn about witchcraft, sometimes reviving old traditions. With the growing trend of “good witch” figures in media, the women once seen as the devils of their time are now being re-embraced and celebrated.

Şahmeran: The Serpent-Woman of Anatolia

Among the rich legends of Anatolia, Şahmeran, a figure with the form of half serpent, half woman, may look at first glance like a “monster woman,” yet she carries a very different meaning. The story of Şahmeran has many variants but the most popular tale is about a wise woman, queen of the serpents, who lives in an underground realm. A young man accidentally enters Şahmeran’s hidden land and spends a long time there, learning from her. When he returns to the human world, a greedy ruler forces him to reveal Şahmeran’s location. Betrayed, Şahmeran is captured and killed in a bathhouse; the sultan who drinks a broth made from her flesh is healed, while he becomes a wise physician with the things she thought her. In this tale, Şahmeran offers healing to humanity through her wisdom, yet falls victim to human greed.

Culturally, Şahmeran’s meaning in Anatolia is highly positive. Although the serpent symbol is viewed as evil in many cultures, in the Şahmeran legend it embodies both poison and cure. Şahmeran represents wisdom and healing; even her death is not in vain, it brings wisdom to people with the help of her teachings. Today, we can see Şahmeran motif around the Anatolia, on glass paintings, carpets and such because people believes that her motif protects their homes.

At the same time, Şahmeran’s half serpent female body creates a parallel with Medusa in Western mythology. In both stories the serpent women used by men because of their knowledge and power. This parallel shows how, across cultures, women’s knowledge and closeness to nature can be perceived as a threat.

Daji: China’s Fox-Spirit

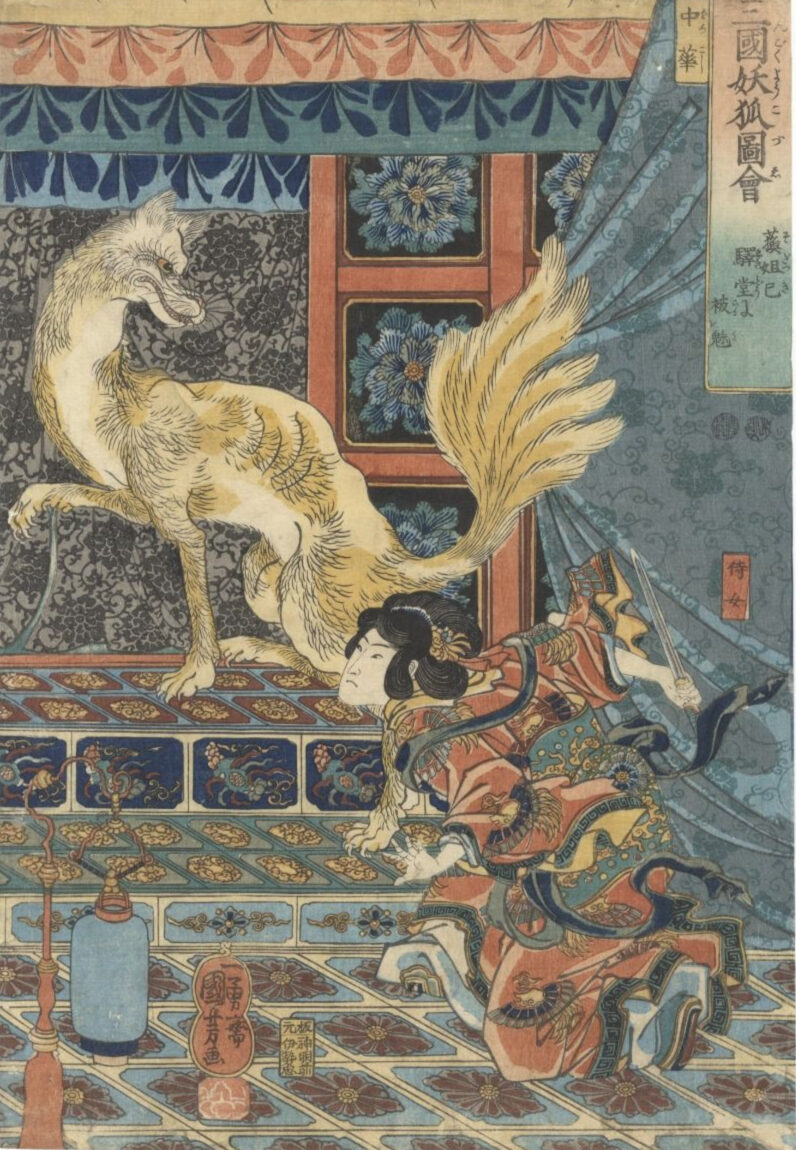

In Chinese mythology, one of the most famous female demon figures the is historical personality named Daji. Daji was the favorite consort of the last Shang ruler, King Zhou, who lived in the 11th century BCE, and she was knowned for her beauty. Historical records portray Daji as a cruel person but later legends go even further, claiming she was in fact a nine-tailed fox spirit (hulijing). This belief was popularized in works such as the novel Fengshen Yanyi. According to the story, the fox spirit Daji enters the body of the real Daji, seduces King Zhou, and weakens his mind and morals. Under her influence, the king did unimaginable cruelties on the people, invents new forms of torture. In the end, this misrule leads to the collapse of the Shang dynasty; the newly founded Zhou dynasty accuses Daji of being a witch-fox and has her executed.

The Daji legend is considered one of the earliest examples in Chinese culture of the beautiful but bad woman. During the Song dynasty, the emperor banned fox-spirit cults associated with Daji. In Chinese art and opera there are scenes depicting Daji as a fox; in traditional paintings she sometimes appears with a fox tail behind her. In the 19th century, Japanese ukiyo-e artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi also portrayed Daji in nine tailed fox form. These images reflect a patriarchal fear within an Eastern context: a beautiful, magnetic woman is turned into a demonic being who brings down male power.

Throughout history patriarchal societies branded women they could not control or those who fell outside the norm as “demons,” “monsters,” or “witches”. Today, women are rereading their old roles in horror tales and reinterpreted them as emblems of resistance. Today many can see Lilith as the first woman to defy patriarchy, Medusa as symbol of justice, witches as an icon of wisdom and the list goes on.

This transformation is visible in the art world as well by the help of the artists reanalysing these myths through a female gaze, casting light on women who were left in the dark like Kiki Smith’s Lilith. Lilith by Kiki Smith is a life sized bronze figure with glass eyes and a twisted head to meet the viewer’s gaze. Instead of a monster, Smith gives us a survivor who rejects being viewed by men in a passive way. An old tale which demonised a woman has a feminist reversal that turns a vilified archetype into a vigilant, embodied presence.

Women are now reclaiming their stories and rather than blaming themselves, they are now learning the reasons behind being demonized. Societies need a common enemy to hold themselves together because if they are not collectively hating the same thing they start to hate each other and throughout history, women have been turned into society’s shared enemy to keep the patriarchy alive. Patriarchy still wants the same thing but women are standing together against it more than ever day by day because they are more aware and they transformed their silence into solidarity.