How did the idea for the exhibition in Istanbul come about?

Murat Pilevneli contacted me and said he was genuinely interested in my work and had been following it for a long time. At the time, I was in Spain for the opening of my retrospective exhibition, Grunts, hoots, whimpers, barks and screams, at the Helga de Alvear Museum. We had dinner and chatted the day before the opening. He asked me if I wanted to do an exhibition. I had never had an exhibition in Turkey before, or even been there, so I definitely said “yes.” The world is a big place, and even though I’m in many museum collections, most people don’t know me; so doing as many exhibitions as I can makes me happy.

Do you have any impressions about Turkey?

I don’t know what to expect. Everyone says it’s wonderful—we’ll see.

We are going through a difficult period for freedom of expression.

This is quite universal. It’s like this everywhere right now.

We thought we’d come to our senses after the pandemic, but we seem more primitive than ever.

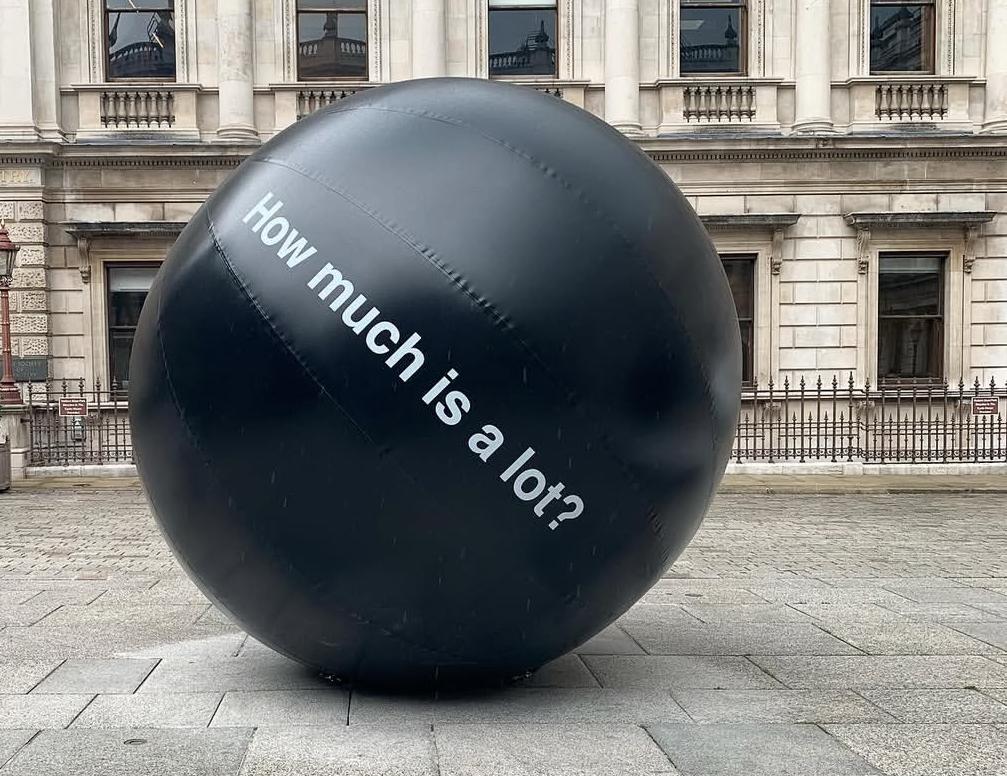

I thought we’d become more sophisticated and learn from our obsession with greed and hoarding. But we haven’t learned the value of time or where to focus our attention—in fact, we waste both more than ever.

You use animatronic technology, don’t you? You bring inanimate objects to life?

My animals and my fairy tales allow me to express my thoughts without taking full responsibility. I make sculptures, animal sculptures. I give them life; I give them a voice. I say what I want to say through them. That way, people listen to things they wouldn’t normally listen to if I told them. The audience approaches these sculptures with a kind of empathy, care, and protective feeling; they feel a kind of nurturing, possessive feeling towards the object that gives them the experience. At that moment, I control their feelings and thoughts. That’s actually what I do. The audience approaches with empathy and attention, and I can shape their experiences psychologically.

Does it work?

Sometimes it does.

Your animatronic mouse sculptures titled The Triology were most recently exhibited at Palazzo Grassi and Punta della Dogana during the Venice Biennale and generated significant buzz. (Three tiny mouse sculptures emerging from the wall convey the artist’s philosophical monologue in a childlike voice.)

Millions of people around the world saw them. But I can’t produce mice forever. Art is about trying, making mistakes, learning, and pushing boundaries; not just repeating the same thing.

Doesn’t the voice of one of these mice belong to your daughter?

Yes, my middle daughter, Penelope, is now 12. I work with all three of my children in different ways.

Will there be street cat sculptures at your Istanbul exhibition? Is there a connection to the Istanbul Biennial’s theme, “Three-Legged Cat”?

No, I didn’t know that, I just found out… Well, I’ve been working with cats for 15 years; I treat the cat as a kind of symbolic icon, a sign, an iconography. I’ve used many different forms. For example, I made lion sculptures at the Mexico City Zoo. I’ve held exhibitions about kittens; I’ve created spaces in galleries where you can play with kittens. I’ve made sculptures of animatronic sleeping cats. The cats I made for this exhibition are made of marble. They are made of marble sections.

“Perpetual Dualities”

What story do the cats exhibited in Istanbul tell?

The issue here is not just about a stray cat; it is about social identity, modernity, collectivity, and singularity… Of course, bringing a street cat into a gallery offers a silent commentary on the problem of public and private space, those inside and those outside. And this is precisely where the elitist, closed, and selective structure of the art world comes into play; it is often not inclusive or welcoming. Although museums are open to the public, they make little effort to draw in people who know little about art. That’s why a large part of the world can’t help but feel stupid when they think about contemporary art. But in my opinion, every human being is creative and has the right to interpret objects and works of art freely.

My observations are not criticism; they are an expression of a situation I have noticed for a long time. In my life, in my surroundings, and in the world I see, these ‘dualities’ are constantly present. Especially in the art world, but actually in all of society. The duality of public and private space, the distinction between inside and outside, between invited and uninvited, between foreign and familiar… These are constantly operating dualities.

Let’s give an example for dualities…

Another situation I observed in London, for example, the existence of what seems like a different class of people. Walking down the street, you notice a society that views the homeless and the poor as second-class citizens. They are often not even seen as human beings; it’s a soul-crushing distinction. There is a boundary between clean and dirty, and this boundary manifests itself in my art in some way, like the difference between a street cat and a house cat.

Do you personally feel prejudice in your own life?

I understand prejudice a little; for example, people quickly judge who I am and what I can do because I use a wheelchair. They see me as deficient, they feel pity, they underestimate my abilities. They don’t even consider that I am a man, that I have children; they see me as someone imprisoned in a weak and small body. That’s why the idea of a street cat speaks to me so much.

A homeless and independent cat, a cat living in the city on its own… A symbol of the modern world. I am fascinated by the fact that cats are a pluralistic and multi-layered symbol. Their interpretations vary from culture to culture: fertility in Egypt, cuteness in Tokyo, and black cats considered lucky in some cultures and unlucky in others. Art should be the same: captivating, intriguing, thought-provoking, and offering hundreds of layers of meaning. It has no single meaning; if it is the same for everyone, it is no longer art, just communication. Art is uncertainty, multiplicity of meaning, and freedom of interpretation. The more diverse the audience’s interpretations, the more vibrant and exciting the work becomes.

What is good art in your opinion?

Good art captures people, arouses curiosity, and seduces them. Art should compel people to engage with it, to grapple with it. People should feel obligated to interact with art. But at the same time, art can have hundreds of different interpretations. So a work of art does not have a single, fixed meaning. Because if we think about it, if the meaning of a work of art is the same for everyone, then it is no longer art, it is just communication. Why not just tell people directly? If there is no ambiguity in your message and you want everyone to think the same thing, then there is no need for art; that is not art. The role of art is to create miscommunication, ambiguity, and the ability to interpret things as you want. I love interpretations. I collect visitors’ interpretations: the more varied and crazy, the better.

“We Humans Have Failed”

I have a personal question. Could you be, in a sense, fascinated by animals?

The distinctions, differences, clashes, and gaps between animals and humans affect me deeply. Animals have been able to live and survive in this world for a long time without destroying it; we humans haven’t been able to do that. When you compare humans and animals, the chasm you see is a product of our thoughts, a product of the mind. We generally accept reason and intelligence as positive things, but they are not always positive.

There is also a subject that interests me greatly: one of my children is autistic. This idea fascinates me; that is, this “neurotypical” thing we call neurotypicality, our neurotypical characteristics, may actually be a kind of disease of humanity. Because neurotypicality is tied to organizing the world with numbers; when you think about humanity’s invention of numbers, Kronos comes to mind. We invented clocks; there is no time, only clocks, and we invented them. Clocks are used to count down, reminding us of the end of our lives, which is not good for us. Numbers are also used to count accumulation, which makes one think of accelerated capitalism and ultimately leads to the end of the planet. When I think about neurodiversity versus a neurotypical or standard mindset, I actually see it as a superpower or a talent. Some people with neurodiversity have a kind of gift, a power.

In this context, what exactly is neurodiversity in your opinion?

A spectrum of neurological differences. People think they rule over all animals, all of nature.

I share my life with several street dogs, and my impression is that they are much fairer than humans.

In the work titled The Magpie’s Tale (Life’s a bite), a fable I wrote about greed, the work is being read. It’s a story written like a moral lesson. In England, there are many superstitions about magpies. In this exhibition, a magpie is placed on the ceiling of a modern-looking office. The ceiling symbolizes capitalism. There is nothing in the room, just a large empty space. A tile has come loose from the ceiling, and there is a magpie inside. In English culture, magpies are associated with stealing shiny objects. So there is also a capitalist game involved. This is one of the works in my Istanbul exhibition. The other is “The Stone Cats – Public / Private series,” an installation consisting of 25 cats. What is important is that these are installations, not sculptures. Because there are more of them than viewers, it is important that they make viewers feel surrounded. In other words, in this exhibition, the viewer is uninvited and unwanted, and the power of the cats, who are in the majority, comes to the fore. Half of the cats are resting, half are exploring the gallery; they are everywhere—in the bathroom, on the stairs, in the corridor, on the table… everywhere. They are not sculptures, but are presented almost like photographic moments of a narrative.

©️ Ryan Gander; Courtesy the artist.

Do you also have paintings?

I don’t paint very often, so this is a big deal for me. I think they’re very interesting; otherwise, I wouldn’t do them. These paintings aren’t decorative; they’re conceptual works. Words drawn on film and then painted in very large sizes. Engraved on photographs. My father used to do this when he traveled; he would engrave the place name and use it as a title in his slide shows. If you ask why conceptual, when we think of a painting in the traditional sense, we expect to see an image. But here, there is no image; there is information. Each viewer imagines their own painting. These are landscape paintings, there are place names: Washington DC, Istanbul, Chester… Everyone will create the image according to their own imagination. It’s also about privilege, time, and attention. Money gives people a great privilege; when you have money, you have free time, otherwise, you spend all your time trying to earn money to survive. Travel and experience are a great privilege.

Yes, poverty leads to immobility, doesn’t it?

Yes, that’s why these place paintings are very important to me, because there is also an economic divide. Some people can travel to places, experience them, while others cannot. The paintings they imagine from the words I carve will also differ according to their experiences.

And of course, there is a mosquito in the exhibition, isn’t there?

The mosquito… a creature people despise, one that spreads disease and causes harm. I once read a statistic—I’m not sure how accurate it is—but apparently the animal responsible for the most human deaths is the mosquito, due to malaria and other illnesses. Humanity’s greatest enemy: countless in number, tiny in scale.

In this exhibition, too, a mosquito sculpture is placed on the books lying on the floor. It sits on top of the books on the table, too. Throughout the exhibition, it keeps shifting between dying, half-alive, and moving. When the exhibition ends, the power is shut off. I give it life—but a life that is already destined to end.

I now include one in every exhibition. These mosquitoes have become a kind of hidden signature for me.

“Art Based on Identity Is Narcissistic and Self-Centered”

Final question. Is there an artwork that has ever taken your breath away?

I don’t like most contemporary art being produced today. It’s too predictable and utterly uninspiring. Most works revolve around identity and politics. I’m interested in universal art—art that can be understood by anyone. Art made through the lens of identity feels narcissistic and self-centered to me. People who aren’t interested in politics or identity issues will stop making art, stop writing about art, stop curating art. And then art will cease to be art; it will turn into nothing more than the commodification of the self. It feels as if people are using their identities. Biography has become more important than the artwork itself—something I absolutely cannot accept. None of the exhibitions I go to exceed my expectations anymore; I don’t learn anything. I genuinely hope contemporary art returns to language, creativity, and semiotics rather than people’s egos.

“Political Contemporary Art Is, Frankly, a Joke”

We’ve been talking for almost an hour, so unfortunately I can’t ask more questions. Is there anything you’d like to add?

I really want to be understood without sounding cliché. Art is incredibly important; it makes people feel alive, it motivates them, it even boosts their confidence. We should value art. We spend so much of our time on meaningless things. We waste so much time, yet we nourish ourselves so little with meaningful experiences—like going to a gallery and trying to understand art. I think that’s why I still make art; I still have love and hope for it. Political contemporary art, in my view, is quite literally a joke. The fact that politics is so trendy in contemporary art truly surprises me. Art made of cliché political slogans and burnt flags is not interesting at all. A real political revolution would be people reclaiming control over their own attention and their own actions. It would be saying: “No, I don’t want this Instagram nonsense. I don’t want these shiny, noisy, glittering giant sculptures. I don’t want glittery unicorn paintings. I want to look at an artwork, spend time with it, and form a deep relationship with it.” That would be the most political act one could perform in the art world. If we’re going to talk about a real political revolution, it would only happen when individuals control their attention and say, “I don’t want this.”

You mean individually?

Collectively as well. The entire contemporary art world is obsessed with politics, yet no one is addressing the truly political issue in art: attention—the real currency of art. I find that extremely strange. It feels almost insane that no one seems to be thinking about this.

Why do you think that is?

Because unless art is about politics or identity, it doesn’t sell. It’s as if the Jerry Springer Show has entered the art world. There has always been politics and identity in art, but in healthy proportions—usually in sophisticated and interesting ways, processed so that the artwork itself mattered. Those themes used to be part of the content or subject matter. But now the situation is reversed—subject and content have overtaken artistic form. That’s the real problem.