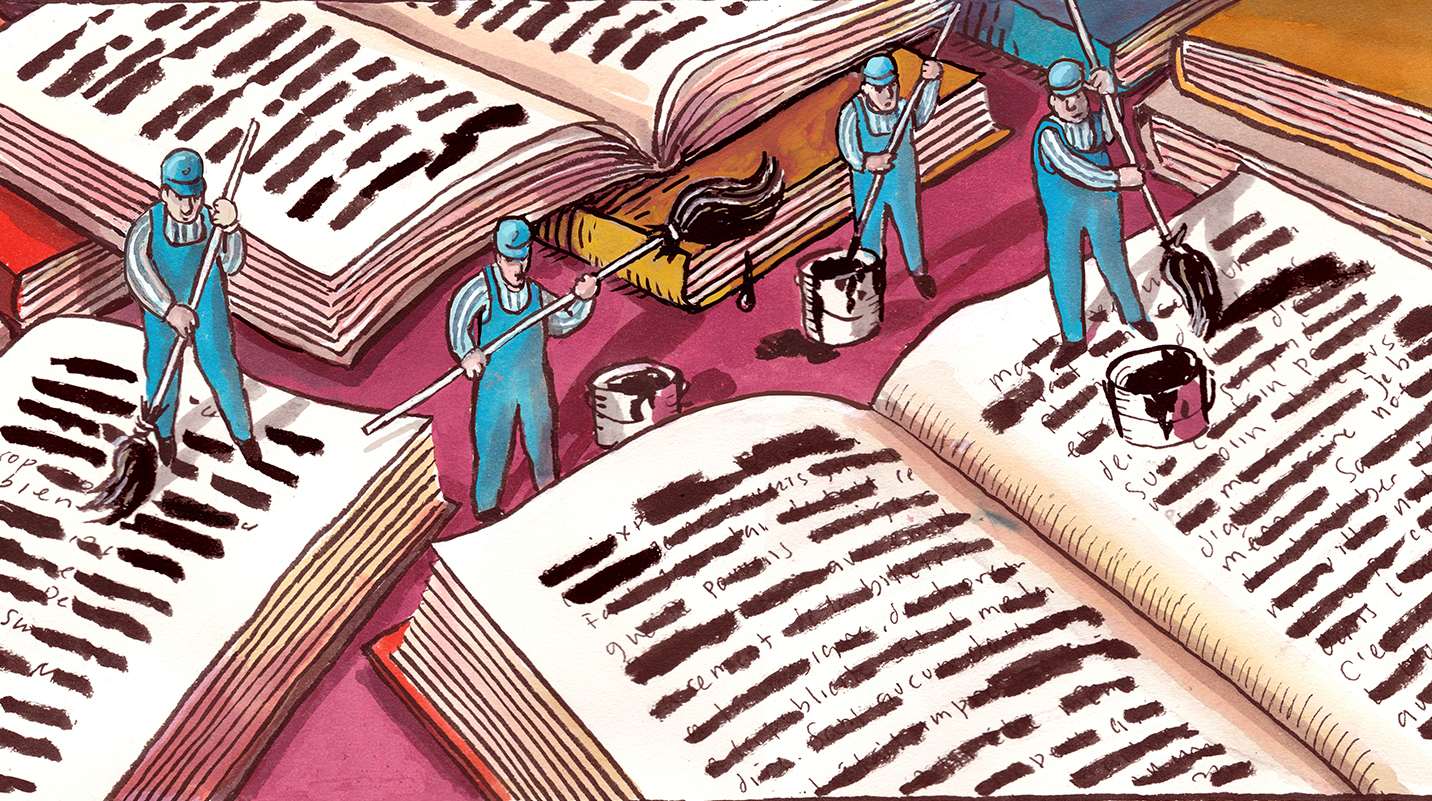

With A Distant Country: The Rebellion of Letters, Selçuk Demirel and Lyliane Adra depict an imaginary country where books are banned, words are considered crimes, and memory is systematically erased, reflecting the invisible mechanisms of censorship and societal silence present in our world today. “From today onwards, it is mandatory to report every citizen caught reading! This person could be… yes, even your grandmother.”

Can you imagine living in such a world? A country where books are banned, words are criminalized, and even grandmothers are reported? But what if this is not just a fantasy? What if this dystopian scenario is merely an extreme version of a reality experienced in many parts of the world today?

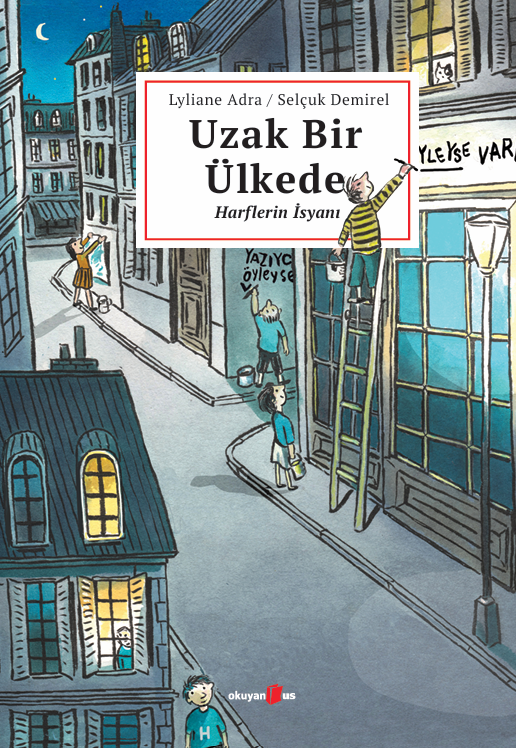

Through their stories set in the fictional country of Veredonia, Selçuk Demirel and Lyliane Adra have not just created a book for children; they have touched upon one of the deepest wounds of our time. A Distant Country: The Rebellion of Letters reminds us how vital a space for resistance art and literature can be in a world where knowledge battles ignorance, freedom struggles against oppression, and memory fights against oblivion.

A Universal Portrait of Societal Silence

In an era where George Orwell’s prophecy “Who controls the past controls the future” seems to materialize, there is a deeper concern echoing in the voices of these two artists: the systematic attempt to destroy the most sacred realms of the human spirit—imagination, empathy, and the ability to remember. The book portrays a world where reading is forbidden, words are criminalized, and bookshelves are silently emptied. Yet the imaginary country of Veredonia feels far more familiar than expected; it is a universal portrait of censorship, memory loss, and societal silence.

Veredonia is a seemingly tranquil country, known for its lush hills and turbulent rivers—until Monsieur Octavio LePetit comes to power in the presidential elections… He harbors a secret so powerful that its revelation could change the fate of the nation. Books are banned, newspapers are shut down, schools are placed under strict surveillance, and it becomes mandatory to report anyone caught reading. This is not merely a ban on paper and ink; it is an all-out war against memory, curiosity, and imagination. We discussed all this with Selçuk Demirel and Lyliane Adra.

Selçuk Demirel / Lyliane Adra, A Distant Country: The Rebellion of Letters

Your book depicts the struggle between knowledge and ignorance, freedom and oppression, silence and speech. Considering that books are still banned and freedom of expression restricted in many parts of the world today, how did writing and illustrating this book feel as a responsibility for you?

Selçuk Demirel: The world is our home. When thinking, writing, or drawing, the borders and differences between countries—color, race, religion, language, cuisine—disappear. Thus, there is a common language that all humans can understand. Even if we use different languages, terms like “freedom, solidarity, poverty, wealth, exploitation, oppression, violence, fear, compassion, empathy, love, and hate” exist in every language. Saying “LOVE” conveys the same meaning in India or among the Eskimos. With this in mind, we decided to tell this story set in a distant country we call Veredonia. We aimed to express, through words and illustrations, the absurdity of life suddenly collapsing into chaos and the unbearable reduction of everything to one man’s knowledge and experience.

“Freedom of Expression is Being Silenced”

Lyliane Adra: I felt a tremendous sense of responsibility, but at the same time, there was a quiet sense of urgency inside me. Although this book is written for children, it carries echoes of the world we live in. Even today, in some countries, books are monitored, censored, or, at the very least, made inaccessible. Therefore, the possibility of understanding our present is also taken away. Freedom of expression is silenced, words are controlled. I could not remain silent in the face of all this.

I wrote this book for both children and adults because I wholeheartedly believe that stories have the power to enlighten minds, provoke thought, and sometimes even heal. Children’s capacity is far greater than we imagine. They can notice injustice, sense when something is wrong. My aim was to create a space for them where resistance is expressed through words, books, and imagination. Writing such a story meant acknowledging that memory, knowledge, and freedom are our most precious treasures that we must all protect together; without resorting to violence, through creativity, courage, and solidarity.

How did your process of creating this book together develop? Do you develop the text and visual language simultaneously, or does one come after the other?

Selçuk Demirel: One of the advantages of living in the same house is having the opportunity to talk to each other and think together about the story. In fact, everyone worked in their own corner. We progressed by showing and reading the text and illustrations to each other. I thought for a long time about which technique I should use to illustrate this story. In the end, I continued in the same rhythm as I always work. I did not make a distinction between children and adults. In fact, text and illustration flow through two separate channels, meet, and become like a single river flowing into the sea…

So, did you write and illustrate this story for those who are truly “far away,” or as a warning against the “dark possibilities” closest to us?

Selçuk Demirel: The “distant” country we imagined as Vérédonia is both far away and very close, and sometimes it is a country we are in. If the world is our home, then in fact, no place is truly far.

The story even calls for forgetting the past. We are reminded of George Orwell’s principle, “Who controls the past controls the future.” How do you connect this forced forgetting with the suppression of memory?

Lyliane Adra: Erasing the past is a difficult but, unfortunately, quite real strategy in many forms of oppression. When memories, books, and testimonies are erased, the possibility of understanding the present and, therefore, questioning it, also disappears. George Orwell’s saying, “Who controls the past controls the future,” perfectly summarizes this mechanism of power: Depriving people of their history robs them of their roots, their identity, and their ability to imagine another world.

In our book, asking children to forget their past is a powerful form of symbolic violence. It attempts to deprive them not only of what they are but also of what they could become. Without memory, there is no continuity, no possibility of rebellion, no legacy to pass on.

However, history can find a way for memory to survive: in a song, a notebook, a whispered word, a child’s game. The book emphasizes this resistance. Resistance emerges through hidden words, shared memories, books hidden at the last minute. It is a salute to the young and old alike who refuse to be erased and fight to keep the future open.

In your view, how can literature and art give a voice to silenced communities?

Selçuk Demirel: As I said before, I think the common language of humanity is art, literature, music, and cinema. The emotion and excitement created by a work of art resonates everywhere, across all cultures and social layers. Therefore, we can express what we want not by shouting, calling, or fighting, but quietly, through writing and drawing.

Lyliane Adra: Literature and art have tremendous power to break through the walls of censorship, indifference, or oblivion. When a community is silenced, words do not disappear; they change place, transform, and seek other channels for expression. Often, their reemergence happens through art. Literature can make visible the people we do not want to see, tell the stories others try to erase, and build bridges between readers and realities unknown or hidden from them. It says: “Look. Listen. Feel.” Without imposing a narrative, it invites understanding and empathy.

Art, in all its forms, also provides a space for reclaiming. Creating in defiance of the silenced becomes an act of resistance: “I am here. I am making a voice. I exist.” Even when words fail, a painting or a song can carry a previously unheard scream. In our book, the voice belongs to children. Yet, they represent everyone whose rights to think, imagine, and remember are under threat. Literature hands them a microphone. And sometimes, the readers themselves become the carriers of voices rediscovered.

“From today, every citizen caught reading must be reported! This person is yours… Yes, even your grandmother.” Book burning has historically been one of the most symbolic acts of totalitarian regimes. Do you think the desire to destroy the written word is an anger not only at content but at remembering and thinking? Were you inspired by such historical scenes when writing the character LePetit?

Selçuk Demirel: LePetit is essentially a caricature of a person with his appearance, clothes, mustache, and beard. At the peak of all the arrogance and self-importance brought by ignorance, he is self-assured. He believes everything he doesn’t possess is worthless and unnecessary. If you can’t read or write, then why bother with a book!

Lyliane Adra: Yes, absolutely… Book burning goes beyond rejecting the content; it is an attack on thought itself. It targets collective memory and the idea that words can freely circulate, awaken, and provoke reflection. It is a way of saying: “I don’t just want to silence what is said; I want to eliminate even the possibility of remembering it.”

The character President LePetit embodies the deep anxiety some powers have: the fear of losing control over minds. Like all tyrants, he knows very well that ideas, not weapons, destroy empires. That’s why he tries to control everything: books, memories, even emotions. He desires a smooth, obedient, memoryless country because it is easier to govern a people without memory. Certain historical scenes have always deeply affected me: Nazi-era book burnings, China’s Cultural Revolution, and more recently, large-scale censorship in authoritarian regimes… In all these examples, the books burned are only the visible part; what is truly targeted is the freedom to think differently. But history also shows this: the rage against thought can never fully prevail. Somewhere, someone always hides a word, a book, or a song. And everything begins to sprout again.

This resistance, especially carried by children who seem to have lost memory, is what I wanted to bring to life in my characters. Despite LePetit’s desire to destroy, he can never silence what is secretly passed on, hidden in glances, or expressed through love for words.

“From today, every citizen caught reading must be reported! This person is yours… Yes, even your grandmother.” Informing is not just a tool of power but also damages trust within society. How do you think today’s “invisible censorship” works? How does fear dissolve social bonds?

Selçuk Demirel: This is a human condition: whether in Turkey, France, or McCarthy-era America, it’s a very effective mechanism—fear and worship of power, wanting to be on the side of the powerful for protection. I recall during the 12 March 1971 military coup, when they called on “informing citizens” over the radio.

Lyliane Adra: Informing creates a pervasive atmosphere of suspicion: we no longer know who to trust. When forced to inform on someone you love—a parent, friend, or teacher—the one attacked is not just the other person, but the bond that unites you.

This is a subtle way of isolating individuals, depriving them of all forms of solidarity. Therefore, in our book, the absurd instruction to inform even on one’s grandmother reveals the depths of inhumanity of a system based on fear.

Today, censorship may not always be visible but is still applied. When we no longer dare to speak, write, or even think due to fear of rejection, harassment, or retaliation, it manifests as self-censorship. These pressures can be social, economic, or ideological. We no longer burn books, but we can render them invisible or inaudible. Voices can be drowned by other noise or excluded from public spaces. In this context, fear becomes a highly effective control tool. It destroys trust, pushes people inward, and silences them even in the face of injustice. This is precisely what authoritarian regimes—and the subtler dynamics of our times—want: divided, lost, voiceless individuals.

Yet there is always hope that bonds can be rebuilt. Through listening, art, collective reading. Sometimes, breaking isolation requires just one word read aloud, an informed gaze, or a secret act of courage. Our book is about that: how solidarity is reborn even in voids under surveillance. And how literature sometimes becomes a way to reconnect, first quietly, then loudly.

In the book, the people’s uprising sprouts from a memory space created together by children and the elderly. Why is intergenerational solidarity important for memory and resistance?

Selçuk Demirel: Children are the future; the elderly are memory incarnate. Each carries a different type of knowledge. If we leave children alone, they may lack guidance. If elders do not pass on their experiences, memory fades. Resistance is built on the intertwining of these two.

Lyliane Adra: Yes. Memory cannot be preserved by one generation alone. Intergenerational solidarity is a powerful tool to protect not only what has been lived but what is imagined. When the past, present, and future meet, the continuity of resistance is ensured. The book shows this concretely: together, they hide, read, draw, and remember. Through this union, a secret yet powerful domain of resistance is created. It demonstrates that the fight for freedom and memory is not a solo struggle; it is collective, human, and continuous.

In this book, we deliberately tried to show the difference between these two generations: the indoctrinated children, the elderly, and the silenced adults. Yet it is precisely these same groups who secretly come together to preserve memories, forbidden words, and erased stories. This pact between memory and imagination transforms into a force of liberation. In today’s world—often fragmented by age, speed, or technology—rebuilding intergenerational bonds becomes almost a political act.

This is not about returning to the past, but about constructing a future on firmer, more humane foundations. Young people need the stories of those who came before them to understand where they come from. Adults, in turn, need to feel that what they have experienced, shared, and loved has not disappeared. Intergenerational alliances form a gentle yet powerful form of resistance, and they may hold one of the keys to ensuring that neither oneself nor others are ever truly lost.