The Artemisia Gentileschi: Courage and Passion exhibition at the Palazzo Ducale in Genova disappoints in its storytelling and resorts to sensationalizing the life of the pioneering artist.

Curated collaboratively by Agostino D’Orazio and Anna Orlando from Palazzo Ducale, along with Arthemisia, a company known for producing blockbuster exhibitions in Italy, the exhibition claims to offer a “faithful portrait of the complex personality of one of the most celebrated artists of all time.” However, it ultimately falls short, presenting a one-dimensional portrayal of Gentileschi that prioritizes sensationalism over a nuanced celebration of her artistic achievements.

First recorded rape trial

Gentileschi, a prominent figure of her era, was the first woman admitted to the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno (Academy of the Arts of Drawing) in Florence. A master of portraiture within the Baroque movement, her canvases depicted women as active protagonists rather than passive subjects of the male gaze. However, Gentileschi’s artistic legacy has often been overshadowed by the violence she endured in 1611 at the hands of the painter Agostino Tassi. This incident led to the first recorded rape trial in history, tarnishing Gentileschi’s reputation and compelling her to flee Rome and adopt a new identity.

The exhibition predominantly revolves around these traumatic events. Upon entering, visitors are immediately confronted with a timeline detailing “Artemisia’s abuse,” accompanied by a map illustrating the locations where the violence transpired and the courtroom of the trial. This sets the tone for the subsequent rooms. The following galleries showcase many of Gentileschi’s portraits, often juxtaposed with those of her male contemporaries, including Caravaggio, her father Orazio Gentileschi, and Tassi—her convicted abuser, described in wall texts as possessing talent alongside a “bad temper.”

Critics have labeled one section of the exhibition as the “rape room,” which is arguably the most disturbing aspect of the display. This darkened space features a bloodied bed at its center, surrounded by projections of Gentileschi’s paintings, all depicted with dripping blood. Adding to the eerie atmosphere is the haunting voice of an actress reciting Gentileschi’s testimonies from the trial, vividly recreating the artist’s experience of rape in painstaking detail.

Protesting the exhibition

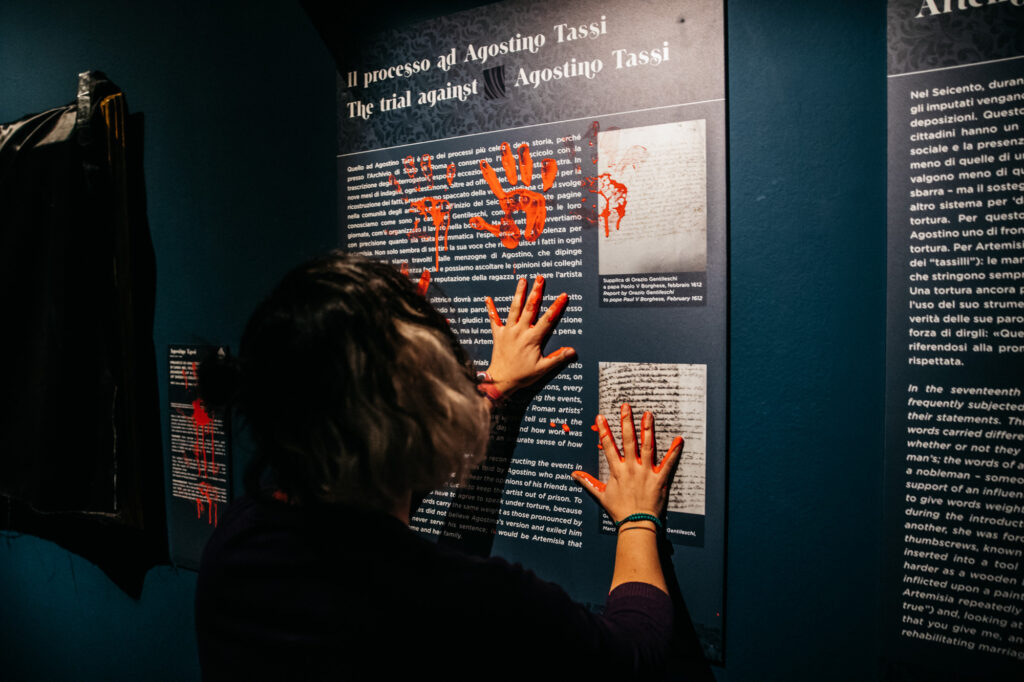

As the exhibition continued, activists gathered at Genoa’s Palazzo to voice their protests. Criticism has been directed at the exhibition by various groups, who argue that it exploits the painter’s sexual trauma and unfairly platforms her convicted rapist, Agostino Tassi. Led by the anti-patriarchal advocacy group Bruciamo Tutto (Let’s Burn Everything), the protest took place on March 29. During the demonstration, activists concealed three of Tassi’s paintings on display and splattered red paint, drawing attention to Italy’s ongoing issues with domestic violence and femicide.

The press release by Bruciamo Tutto said: “We are covering this painting because we cannot stand the paintings of Artemisia’s rapist being hung next to hers.”

“We are deeply disturbed by the decision to sensationalize the rape,” she continued, referring to the exhibition’s widely criticized “rape room,” featuring a dark space with a blood-soaked bed and an audio recital of Gentileschi’s harrowing testimony from her 1612 rape trial.

The installation has been condemned by visitors and critics, including Italian writer Ginevra Rollo, who wrote in a recent opinion piece for Hyperallergic that the exhibition “presents a one-sided portrayal of Gentileschi, sacrificing a celebration of the artist’s body of work for a spectacle of violence.”

During the protest, activists affixed black cloth to the frames of Tassi’s paintings, obscuring them from view, while also leaving behind a pool of red paint on the floor. Crimson handprints and footprints adorned the walls and floor, serving as a powerful visual statement.