An exhibition that, rather than “equipping” the visitor with knowledge, lays bare how knowledge is distributed, poses a quiet yet sharp question: what happens when narratives of “origin” are delivered in a dominant voice or not told at all?… Whose origin story makes it into textbooks, which lineages are bracketed off in museums, and which aesthetic inheritances are claimed as “universal”? Özge Topçu’s title The Grace of Unknowing speaks directly to this politics: here, unknowing is not a lack, but a condition produced by historical selectivity. The exhibition brings together two main bodies of work, Re-deciphered Scripts and Celestial Stalagmites besides Topçu’s many works, to trace how cultural beginnings are narrated through mythology, geography, and history, and how much is routinely edited out of those narrations.

Topçu, a multimedia artist whose practice is centered on installation and research, works from a Mediterranean vantage point shaped by edges and crossings: born in Kırklareli and based between Lisbon and Istanbul, she frames the sea less as a border than as a charged field where identities are assembled, ranked, and mythologized. Her method draws from archaeology, linguistics, mythology, and research, but the exhibition does not behave like a lecture. Instead, it stages research as atmosphere, materialized as propositions, not conclusions.

Along one axis of the exhibition, the Phoenician script that Topçu inscribes or shapes into terracotta brings into view the side of the Mediterranean’s alphabetic legacy that never quite enters the “canon”: even today, the historical framework that acknowledges the Greek alphabet’s derivation from Phoenician (and the impact of that transmission on European writing systems) can remain submerged beneath the dominant Hellenistic sheen of many prevailing narratives.[1] Looking across the artist’s works, it becomes clear that this logic of veiling is not confined to writing but is also embedded in number: the way “zero” enters European languages via the Arabic ṣifr with its layered meanings of “cipher” and “code” reminds us that the circulation of knowledge always carries a politics of translation.

Along another axis, Islamic geometric forms carried from al-Andalus into the Mediterranean such as twelve-point star schemas (for instance, AB-CS12, which references both Seljuk visual vocabularies and the European Union flag) migrate like motifs: when context falls away they flatten into “ornament,” and when context returns they re-emerge as “memory.” Topçu’s practice holds the visitor precisely at this threshold, between attraction and responsibility, inviting us not to locate an origin but to see how origins are constructed.

The most immediate encounter in the exhibition is sculptural. Terracotta forms are arranged on smooth white plinths and long tables; their warm clay tones resisting the “cool” authority of gallery display. These objects resemble letters, yet refuse legibility. They twist and lean like characters that have forgotten their own grammar, hollow at the ends, sometimes resembling pipes or wind instruments, as if language were literally something you could breathe through. The gallery text frames Re-deciphered Scripts as a turn toward the Phoenician alphabet, one of the earliest Mediterranean writing systems, whose influence, Topçu suggests, lingers beneath the brighter, more canonized Hellenistic narratives of Western origin.

What makes these “sculptures” compelling is their refusal to perform as evidence. They evoke archaeological fragments, but they do not deliver the comfort archaeology is often made to promise: a stable story, a verified lineage, a rightful inheritance. Instead, Topçu treats language as “tender material,” marked by transmission, misattribution, and erasure. The work’s implied fragility matters here: the sculptures look sturdy, yet conceptually they are unstable, meaning slips, ownership blurs, and the very desire to “decipher” becomes suspect. The exhibition text notes that sound deepens this exploration, shifting writing from permanent mark to vibration, an echo rather than a monument.[2] Even without hearing the sound component in the exhibition, the objects already suggest resonance: mouths, openings, chambers, forms that hint that meaning is produced not only by inscription, but by circulation.

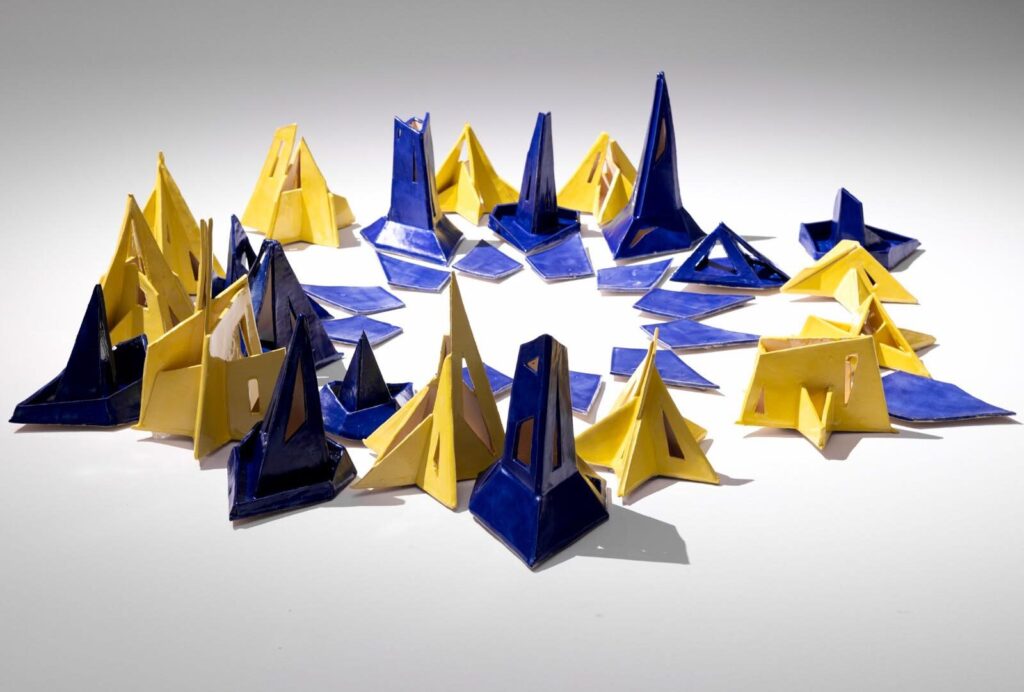

If Re-deciphered Scripts focuses on script as contested inheritance, Celestial Stalagmites moves from writing to ornament, myth, and cosmology. In the images, glazed ceramic elements, deep cobalt and paler blue-grey, gather in clusters like a miniature city or an abstract topography. Some shapes rise like stalagmites or monoliths; others sit as small pyramids, wedges, and apertured modules. The effect is both playful and severe: a speculative landscape where geometry feels like a migrating language. This aligns with the description of the work as drawing on Iberian ceramic traditions “quietly enriched” by Islamic and North African geometries, tracing how motifs drift across regions and detach from their origins.

In Celestial Stalagmites, the ultramarine within the glazes does not read merely as an aesthetic choice; Topçu also brings the colour’s historical burden to the surface: the fact that ultramarine pigment originates in lapis lazuli/the mineral lazurite, and its long-standing associations in antiquity with the representation of the sky, the “divine,” and a sense of sublimity. For the artist, this blue speaks both to that historical image of the sky/infinity and to a chance discovery such as the way a pattern that emerged on the work’s surface “unknowingly” came to resemble the molecular structure of the lazurite mineral itself. In this way, the exhibition builds a bridge between the “terracotta” strand, concerned with the origins of writing, and the “blue” strand, carrying the knowledge of motif and sky: one renders letters unreadable, the other layers light and colour, allowing visitors to experience within the space itself, how much of origin narratives is made visible, and how much is dimmed or filtered out. The mirror positioned above Celestial Stalagmites does more than represent the sky; it re-produces it within the gallery. At the same time, by breaking the gaze, it shifts “unknowing” from an idea into a visual regime: each time, the visitor looks by way of the reflection’s indirection.

Here the exhibition’s title becomes the hinge. The Grace of Unknowing can be read as a permission, an allowance to enter through visual attraction, even if you lack the historical keys. However, Topçu also reveals the stakes of that attraction. When we don’t know the context, symbols can flatten into décor; “influence” becomes a polite euphemism for extraction; ornament becomes portable while its histories become disposable. The exhibition is effective precisely because it does not resolve this tension. It stages unknowing as a charged condition: sometimes innocent, sometimes chosen, often produced by power.

Formally, the exhibition’s clarity supports its argument. The white surfaces, spare placement, and strong overhead light (as seen in documentation) heighten the works’ objecthood while amplifying their instability as carriers of meaning. The exhibition reads accessible in the most basic sense, open sightlines, readable spacing, and works that invite slow looking, yet it also withholds the easy accessibility of “decoding.” That withholding is not elitism; it’s the point. Topçu’s installations do not ask us to solve history, but to notice how histories are built, credited, and made credible, and what we accept as “truth” when we only recognize the surface.

In a broader landscape where contemporary art frequently borrows the aesthetics of the archive, Topçu’s strength is that she turns the archive’s seduction against itself. She does not fetishize antiquity; she questions how antiquity is used. The exhibition leaves you with a lingering ethical aftertaste: not “I learned the origin,” but “why did I want an origin so badly?” That shift, from resolution to resonance, is the exhibition’s most persuasive achievement.

At .artSümer Gallery in Beyoğlu, artist Özge Topçu’s The Grace of Unknowing is on view from January 31 to March 6, 2026.

[1] See for the origin if the Greek Alphabet: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Greek-alphabet?utm_source=chatgpt.com

[2] See the exhibition text: https://www.artsumer.com/artists/41