Museums are thriving; they are doing everything they can to attract and involve more audiences while leaving a mark on society with different museum programs and exhibitions. Yet how is it possible? It’s a huge question: How can a museum remain a knowledge hub today while still organizing exhibitions that play a vital role in society? A conflict arises from this problem, and there is only one solution … The temporary exhibitions. That’s how a museum can differentiate itself as a source of knowledge spillover in society while still maintaining its significance. That’s what the Sakıp Sabancı Museum did with the Suzanne Lacy exhibition.

The exhibition titled ‘To gather, together’ meets the audience with a fragile yet subtle attitude. The exhibition opens a new dimension for the audience, asking about art’s role and power in public, and the museum’s role in active information dissemination. The audience has to be there, ready, and open to everything that Lacy is showing. Her art has political, social, and historical elements adorned with an aesthetic approach.

Lacy’s work involves not only research on social norms or society as a whole but also deep individual research. She puts herself in other women’s shoes and studies their conditions. She brings this approach to the public and introduces a new dimension within the museum, incorporating both feminist and public art. The way she chooses to communicate with the museum audience is through aesthetics and, importantly, through her art’s capacity for learning.

Lacy is creating her public performances to encourage an unconventional way of thinking about museum learning. Is it possible that audiences can both be part of the performance and also learn and participate in education? The question also raises other issues about museums and, importantly, about new museology. What new museology aims to do for the public is similar to what Lacy is doing by sharing her performances in museums.

Sabancı Museum’s exhibition opens with a sentence by Suzanne Lacy, ‘I think art is a very interesting way, though not necessarily the most effective way, to create change.’ The sentence somehow prepares the audience for what they are about to see.

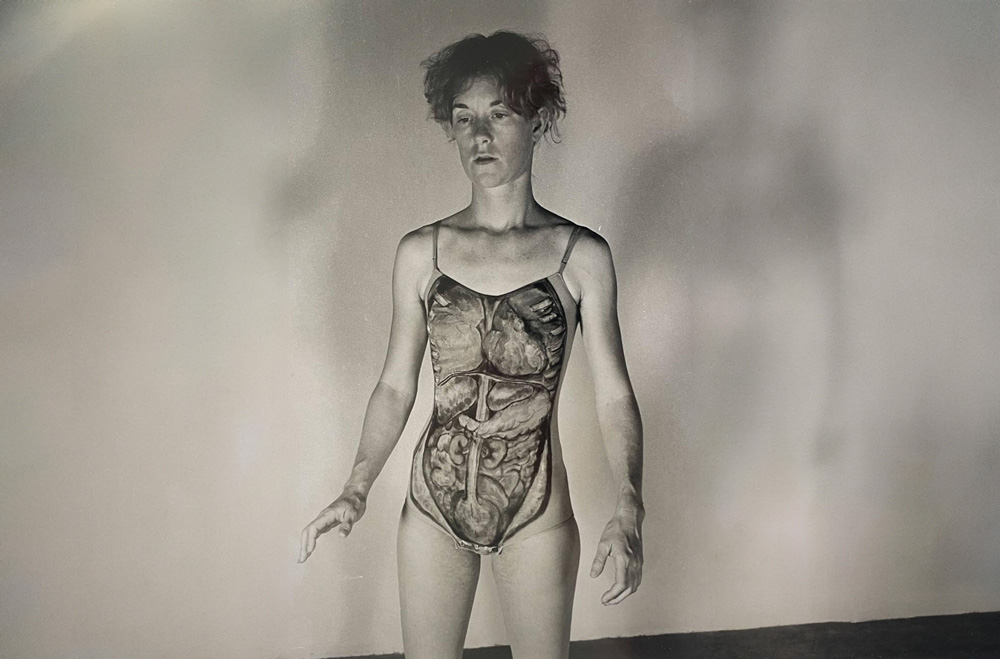

Lacy’s early works stand as a beacon. The photo that opens the exhibition and the suit Lacy wore in that photo (a painted body suit) reveal a woman’s internal organs, continuing the theme of her other works, ‘A Gothic Love Story’ and ‘Cold Hands, Warm Heart’. We see organs and somehow ask ourselves how they are related to being a woman in a society. Lacy tries to open a new page in terms of showing the violence and the hardships of existing as a woman in a society.

These photos have deeper meanings because they are not just aesthetic; they become historical images in feminist art. How can a woman live without fear, without thinking about her existence in anxiety? Maybe just a few questions that people may ask themselves.

‘Your Own Hand’ features one of Lacy’s most important performances at the core of the exhibition. In the video installation, a series of men appear on screen, calmly reading excerpts from letters. The letters describe frightening stories of gender-based and domestic violence—from sexual assault to gang rape and femicide—creating a strong sense of unease.

The footage was shot in Quito, Ecuador, inside a traditional bullfighting arena—a space historically associated with masculinity and rich in rituals of dominance and violence. The circular projection setup places viewers at the center of this arena, directly confronting them with the speakers’ words and steady gazes. The life-size images amplify the performance’s physical and emotional impact, making its influence unmistakably felt.

The exhibition also demands full participation from the audience. The questions written on the wall: ‘Is violence gender-neutral?’, ‘Who’s winning the war on women?’, ‘Are the kids okay?’, ‘Who do you love?’ are all based on women. The audience is asked to write their own questions, opening a dialogue on these issues.

We see the museum as part of the exhibition, but not as an artwork, rather as a participatory element in Suzanne Lacy’s works, since the museum functions as a knowledge center, a mutual learning venue in an art form, and a participatory project within all questions.