With his calm voice, his philosophy of “happy accidents,” and the soothing atmosphere he created on screen, Bob Ross continues to make an impact even 30 years after his death. Rediscovered on television by new generations, the artist’s works are now breaking record after record on the art market. Winter’s Peace, sold at Bonhams Los Angeles, fetched $318,000—marking the highest auction result for Ross to date.

Bob Ross, who once convinced millions in front of their televisions to believe in “happy accidents,” shows no sign of fading into history. The gentle television painter of an era has now resurfaced in auction rooms, this time accompanied by staggering numbers. As his programs once again reach millions, his paintings are experiencing a dramatic surge in value on the art market.

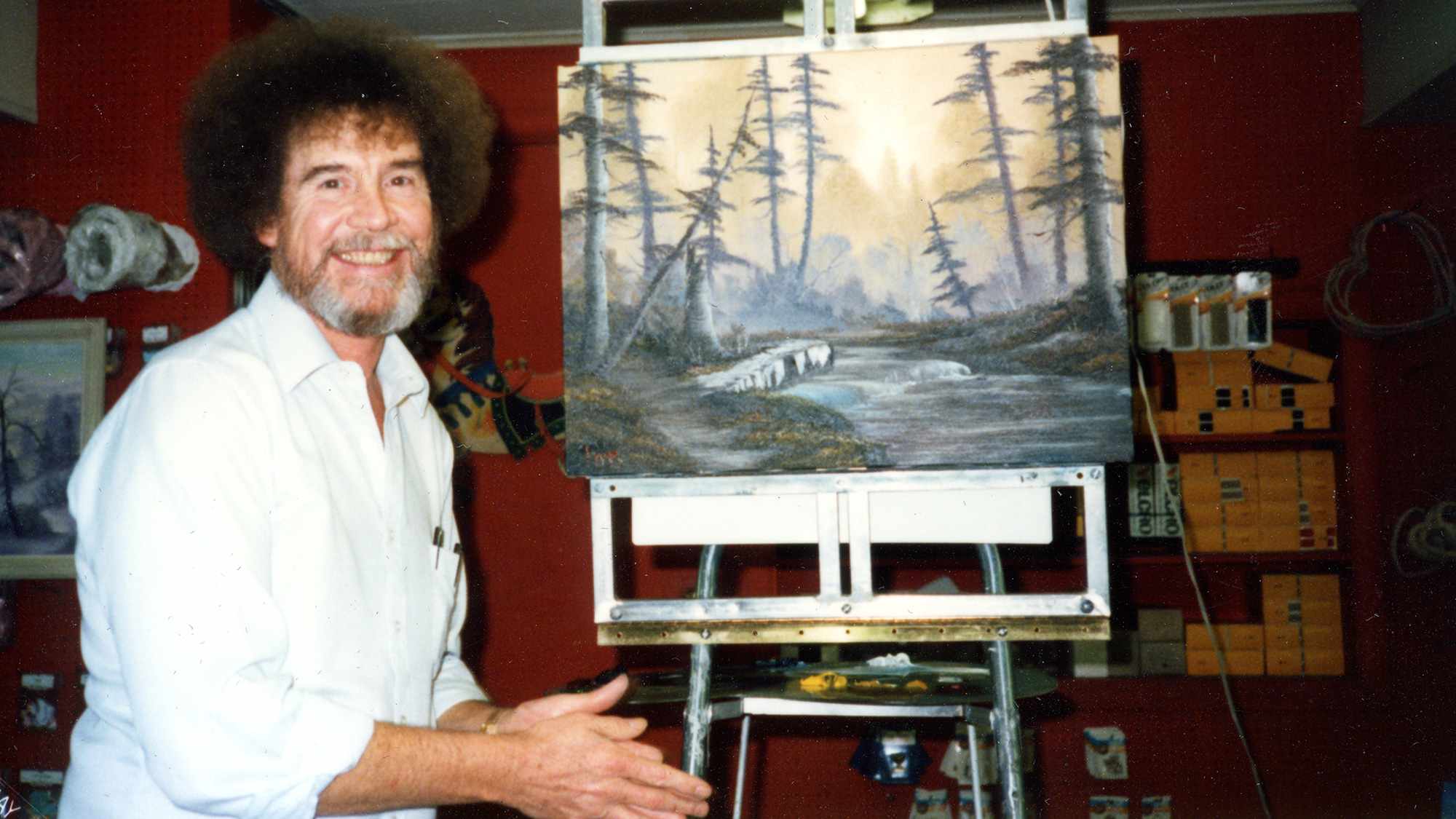

Ross’s previous auction record of $114,800 was tripled on November 11th, when Winter’s Peace (1993) sold for $318,000 including fees at Bonhams Los Angeles. Three original works—Cliffside (1990), Home in the Valley (1993), and Winter’s Peace (1993)—far exceeded their estimated range of $25,000–50,000. Together, the three paintings brought in a total of $662,000. Thus, Bob Ross, once the soft-spoken painter of television, returned to the spotlight decades later—this time with million-dollar figures.

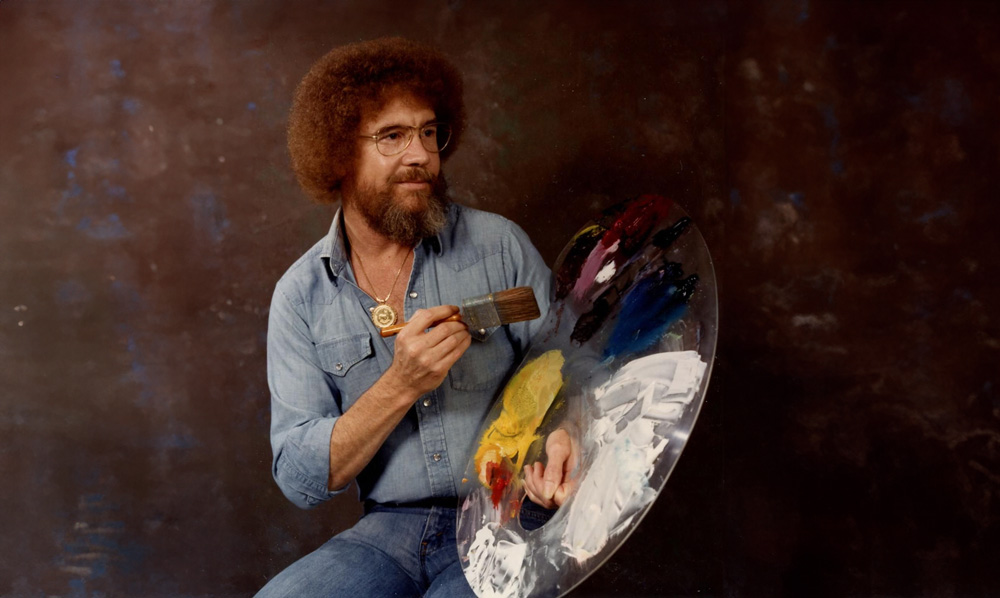

Ross is known not just as a painter, but as the television personality who taught viewers to paint by saying, “It’s not a mistake, just a happy accident.” His show The Joy of Painting (broadcast in Turkey as Resim Sevinci) aired on PBS throughout the 1980s and 1990s, reaching a vast audience in popular culture. Until his untimely death at age 52 in 1995, Ross painted mountains, lakes, and trees in his whisperlike tone—and even appeared in MTV commercials during the channel’s golden age.

Twenty Years in the Army

Born in Florida, Ross joined the U.S. Air Force at 18 and was stationed at the Eielson Air Force Base in Alaska, eventually rising to the rank of master sergeant. By his own admission, he was nothing like the soft-spoken figure later seen on television; instead, he was a stern superior officer who disciplined his subordinates, yelled, and enforced strict routines. He claimed that when he left the Air Force, he vowed never to raise his voice again—explaining the quiet, soothing tone he adopted on camera.

Despite being the face of public television, Ross stated that he never received payment for The Joy of Painting. Due to PBS’s nonprofit structure, the program was produced without fees; Ross earned his income through workshops, books, instructional videos, paint kits, and brushes. His presence on television became the promotional engine for the commercial side of his artistic practice.

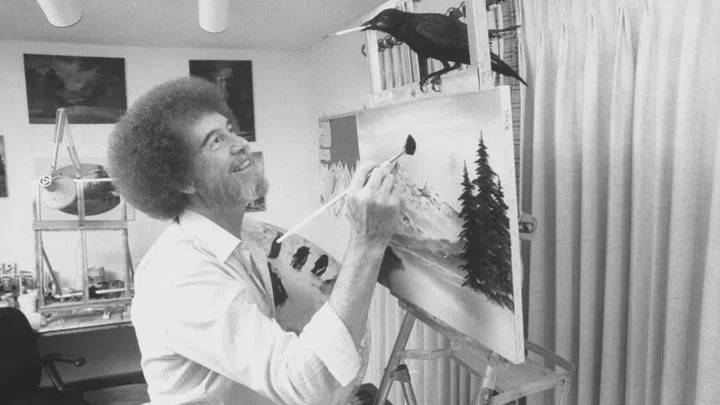

Bob Ross and His Bond With Animals

For each episode, Ross produced three paintings: one for filming, one as a preliminary study, and one for books and detailed shots. Despite this prolific pace, many of his works changed hands through auctions over the years. Provenance—documented ownership tracing back to the artist—has occasionally made Ross paintings a topic of debate in the art market. Today, original Ross paintings rarely appear, and when they do, they easily command prices starting in the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Beyond painting, Ross cultivated a close relationship with animals. While filming in Muncie, Indiana, he collaborated with animal rescue groups; his backyard in Orlando became a rehabilitation space for squirrels and birds. He often brought small animals onto the show, making them part of the program’s charm alongside his landscapes.

Ross’s son, Steven (Steve) Ross—also a painter—appeared frequently throughout the show’s 403 episodes. Although he shared his father’s technique, he developed his own style. After Bob Ross’s death, Steve left Bob Ross Inc. due to disputes and later returned to the art scene through occasional workshops, continuing his father’s legacy in his own way.

Family Secrets and a Contested Legacy

Ross was famously private about his personal life. Nevertheless, scattered accounts reveal moments of complexity: three marriages, children from different relationships, and family stories that surfaced only after his death. These narratives—absent from official documents—live on in oral recollections and fan lore.

Ross’s place in the art world was equally paradoxical. While adored by viewers and the general public, his work was often excluded from the academic canon of “high art.” Ross himself acknowledged this, once saying: “This isn’t fine art, and I’m not telling anyone that it is.” Yet, his democratizing approach inspired countless people to pick up a brush—an achievement many consider invaluable.

His legacy, however, was overshadowed by disputes surrounding Bob Ross Inc. Cofounded by Ross, his wife Jane, and the Kowalski couple, the company’s ownership structure shifted after Jane’s death, leaving Ross a minority shareholder. Conflicts over name, likeness rights, and creative control strained his final years. Though Ross attempted to bequeath his intellectual property to his son Steve, legal proceedings ultimately awarded exclusive rights to the company. Burdened by legal costs, Steve Ross eventually withdrew, unable to continue the fight.

Despite these tensions, Ross frequently collaborated with friends and fellow painters on-air, welcoming figures like Dana Jester and John Thamm. Some episodes highlight portraits and alternative techniques, showcasing Ross as part of a shared creative community—not just a solitary TV painter.

A Lasting Memory

Bob Ross died of lymphoma in 1995 and was laid to rest in Gotha, Florida. His modest grave has since become a pilgrimage site, adorned with tiny paintings, brushes, and figurines—tokens from visitors whose lives he touched.

Through television reruns, the internet, books, and a global array of branded materials, Ross remains not only a nostalgic figure but also a source of comfort for those who seek peace, creativity, or simply a gentle voice reminding them that mistakes can be “happy accidents.”

His legacy endures—quiet, steadfast, and still painting smiles across the world.