The Cultural Map of the Post-Oil Era

Over the past decade, countries across the Arabian Peninsula—particularly Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE)—have witnessed rapid and highly visible developments in the fields of art and culture. From Qatar’s first-ever Art Basel art fair to record-breaking contemporary art auctions at Christie’s Dubai and Sotheby’s Abu Dhabi, and mega-projects such as Maraya, rising in the middle of the desert in Saudi Arabia’s AlUla region, the area has swiftly positioned itself at the center of the global cultural landscape. Museums, biennials, and art fairs emerging from the desert prompt a pressing question: what new narrative of the Gulf is being constructed? The answer, in many ways, lies in oil. Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, Qatar’s diplomacy-driven museum strategies, and the UAE’s transition toward a “creative economy” are all attempts to respond to the same fundamental concern: what kind of economic and political legacy will be left behind in the post-oil era? Undoubtedly, climate change, the growing preference for green energy, and signals pointing to the eventual depletion of oil reserves pose a significant threat to countries such as the UAE, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia, whose economies have long been built on petroleum. Within this context, art and culture are increasingly framed as engines of employment, sources of foreign revenue, and pillars of a new, sustainable economic system for the post-oil future. Yet, this story is far from innocent. Beneath this glossy surface lies a multilayered architecture of power in which art is mobilized not merely as a sign of cultural awakening, but as a strategic instrument for global image-making.

Three Models in the Gulf: Market, Transformation, and Diplomacy

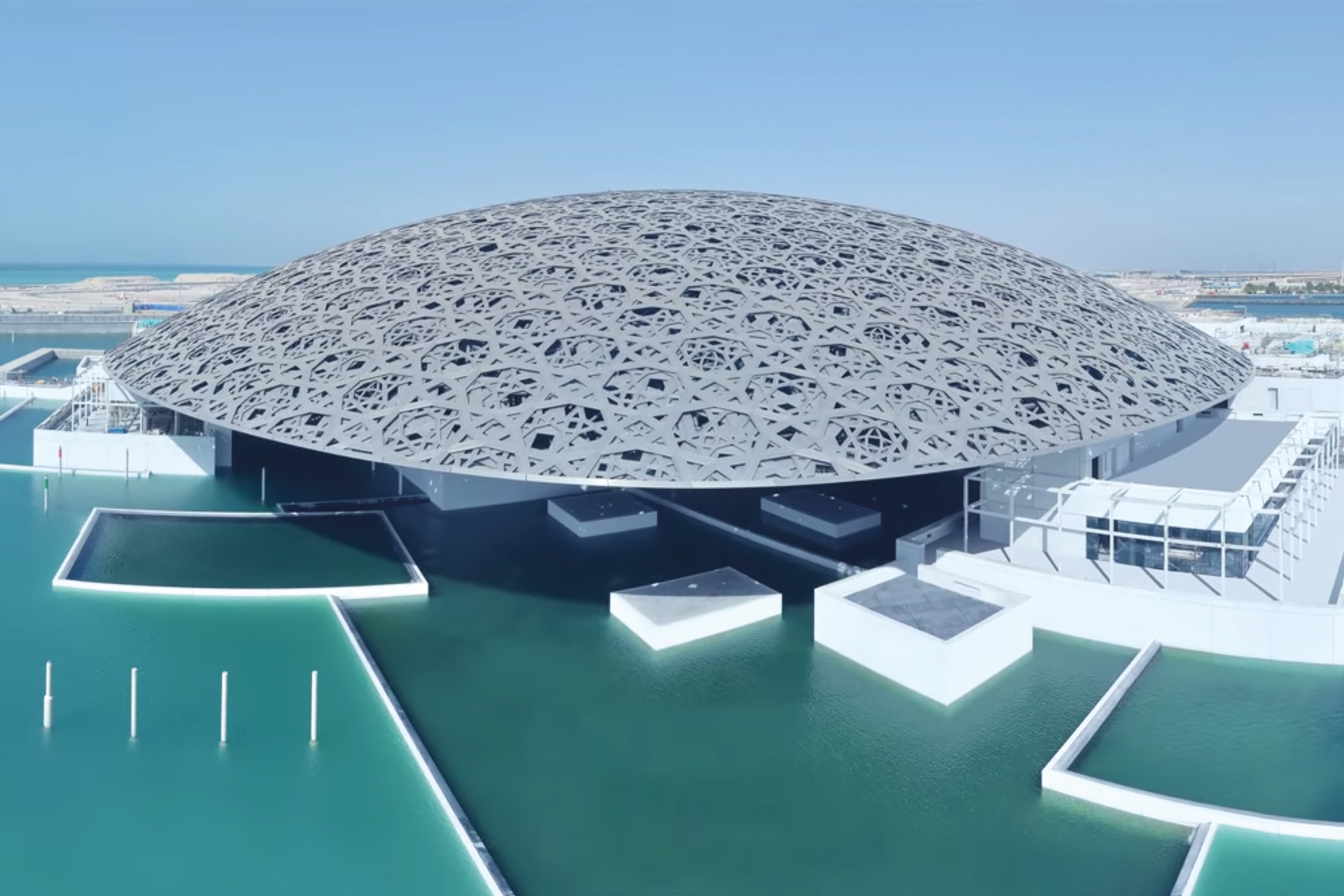

While each country on the Arabian Peninsula pursues distinct cultural policies, three stand out for the intensity and visibility of their activities: The United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar. Among them, the UAE has emerged as one of the most prominent actors in the region, particularly through its cultural programs and innovative museum architecture. Announced in 2021, the National Strategy for Cultural and Creative Industries aims to strengthen the country’s position on the global cultural map, attract creative talent, and structure the creative sectors as a key driver of economic growth. In line with this vision, the UAE has drawn attention through licensing agreements with prestigious, predominantly Europe-based cultural institutions. Abu Dhabi, the capital, sits at the heart of this strategy through the Saadiyat Island Cultural District project, whose development began in the early 2000s. The first major milestone of this transformation was the opening of Louvre Abu Dhabi in 2017, designed by Jean Nouvel. Another significant landmark is Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, designed by Frank Gehry and scheduled to open this year. Through these institutions, the city aims to establish itself as a permanent hub within Western museum networks.

The Culture of the Market: The Dubai Model

Unlike Abu Dhabi, Dubai approaches culture less as a field of public policy and more as a market-driven component integrated with finance, design, real estate, and tourism. The relocation of Middle Eastern headquarters of major auction houses such as Sotheby’s and Christie’s to Dubai has undoubtedly strengthened the city’s position within the global art market. Christie’s opening its doors in Dubai in 2005 can be read as one of the first institutional steps toward the establishment of Western auction systems in the Gulf, while Sotheby’s launch of its Dubai office in 2017 signals that the UAE’s orientation in this field has evolved into a lasting market strategy. Galleries clustered around the Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC) further illustrate a spatial convergence between art and capital. Completing this picture, Art Dubai fair and the Alserkal Avenue project—launched in 2008 through the transformation of a former industrial zone into a hub for independent galleries, artist studios, and design spaces—concretize Dubai’s effort to construct a cultural ecosystem that frames cultural production not merely as a public sphere, but through the lens of creative industries and market dynamics.

Controlled Transformation: Saudi Arabia and Vision 2030

Following the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia is the Gulf country undergoing the most comprehensive transformation in the field of arts and culture. Announced in 2016 under the leadership of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, Vision 2030 aims to diversify the Kingdom’s oil-dependent economic structure and reposition Saudi Arabia as a global hub for investment, tourism, and culture. Within the program, arts and culture assume a strategic role under the heading of a “Vibrant Society.” With the establishment of the Ministry of Culture in 2018, sixteen cultural sectors—ranging from music and cinema to theatre and visual arts—have been brought under an institutional framework. The lifting of the cinema ban that had been in place for 35 years, the introduction of international concerts, and the MDLBeast electronic music festival held in Riyadh in 2019 stand among the most visible social manifestations of this transformation. The showcase of this cultural restructuring, however, lies in mega-projects focused on tourism and image management. Among the most striking of these is AlUla. Long left untouched, Saudi Arabia’s ancient heritage is now staged as a site that translates the visual language of the present through contemporary art installations and iconic structures such as the Maraya Concert Hall. Initiated in 2017, this transformation has turned AlUla from a purely archaeological site into an exclusive destination for cultural tourism. A similar process of reconfiguration can be observed in Diriyah, where the historical roots of the Saudi state are located. Here, symbolic sites of the past are being reimagined as a cultural district that engages with public life. The Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale, first held in 2021, and the Islamic Arts Biennale, launched in 2023, mark key milestones in this ongoing transformation.

Qatar: Influence Through Culture

For Qatar, culture is less a field of national development than a matter of international representation and influence. While the Qatar National Vision 2030 (QNV 2030), announced in 2008, seeks to move the country away from an economy based on oil and natural gas toward a knowledge-based and sustainable model, the cultural backbone of this strategy is formed by Qatar Museums (QM), established in 2005 under the leadership of Sheikha Al Mayassa bint Hamad Al Thani. Within QM, Mathaf is known to house one of the most comprehensive collections of modern and contemporary art in the Arab world. Through institutions such as Mathaf, Qatar Museums has built significant collections that deeply represent Arab modern and contemporary art, while aiming to position Qatar as a visible actor on the international art and cultural scene. Two key museums that concretize Qatar’s cultural vision are the Museum of Islamic Art, designed by I. M. Pei and opened in 2008, and the National Museum of Qatar, inaugurated in 2019 and designed by Jean Nouvel, inspired by the form of a desert rose. Beyond museum spaces, art is extended into the public realm, shaping the country’s everyday landscape. Richard Serra’s monumental steel installation East-West/West-East, placed in Qatar’s Brouq Nature Reserve desert in 2014, reconfigures the perception of scale and nature, while Damien Hirst’s bronze sculpture series The Miraculous Journey, located in front of the Sidra Medical and Research Center in Doha, renders the universal narrative of life and the body visible within a publicly accessible setting. Alongside initiatives aimed at attracting global art fairs such as Art Basel to Doha, Qatar supports this strategy through extensive cultural programming—clearly positioning art and culture as instruments for expanding its international influence.

Reputation Laundering: The Gulf in the Shadow of Art, Capital, and Spectacle

One of the most forceful critiques directed at the cultural surge in the Gulf is that these initiatives can be read not merely as projects of modernization, but as a systematic strategy of art-washing—the strategic deployment of art as a tool of reputational management. Within this framework, art and culture function as a showcase designed to soften the negative perceptions generated by political repression, human rights violations, authoritarian forms of governance, and controversial foreign policy maneuvers. In this way, high-profile museums, biennials, and international collaborations are transformed into symbolic instruments that reinforce regimes’ global legitimacy.

At the same time, advocates of these projects argue that such investments strengthen the region’s cultural infrastructure, open up new spaces for artistic production and circulation, and may, in the long run, pave the way for a more pluralistic public culture.

Mirror Museums and the Politics of Representation

One of the figures who most clearly articulates the theoretical framework of this process is the French political scientist Alexandre Kazerouni. His 2017 book Le miroir des cheikhs: musées et politique dans les principautés du golfe Persique (The Mirror of the Sheikhs: Museums and Politics in the Principalities of the Persian Gulf) examines museums in the Gulf as surfaces of representation oriented toward the West, conceptualizing their political function through the metaphor of the “mirror.”

According to Kazerouni, projects such as Louvre Abu Dhabi, which opened in 2017, and the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi—still unrealized but symbolically significant—function primarily not for local publics but as representational spaces addressed to Western political, economic, and cultural circles, where regimes “reflect” themselves back to the West.

Rather than operating as autonomous sites of artistic production, these museums serve as central actors in the management of global perception. One of the most striking aspects of Kazerouni’s analysis is his focus on the financial structures underpinning these cultural investments, revealing a dense network of relationships woven between the state, ruling dynasties, and international institutional partners.

Hard Networks of Soft Power

He argues that a portion of the funding used for the museums on Saadiyat Island was sourced through the Offset Program Bureau, a mechanism established in 1992 that compelled states selling arms to the United Arab Emirates to reinvest within the country. Later rebranded as the Tawazun Economic Program, this system reveals that cultural investments are far from innocent artistic initiatives; rather, they are embedded within a structure intertwined with the defense industry, state policy, and economic coercion. This configuration undermines the assumption that culture operates as an autonomous realm of “soft power,” detached from military, economic, and geopolitical interests. On the contrary, it demonstrates that art and museum policies have become strategic domains directly linked to the defense industry, diplomatic bargaining, and intergovernmental interest networks.

A similar opacity and concentration of power can also be observed in the Saudi Arabian context. Amr bin Saleh Abdulrahman Al-Madani, CEO of the Royal Commission for AlUla—the body responsible for developing one of the country’s most prestigious cultural projects—was arrested on January 28, 2024, by Saudi Arabia’s anti-corruption authority on charges of abuse of power and money laundering. This development once again exposed how mega-projects are built upon fragile oversight mechanisms.

By its very nature, the art market operates through high-value, easily transportable works whose pricing is largely subjective, rendering it structurally vulnerable to money laundering on a global scale. The expansion of auction giants such as Sotheby’s and Christie’s into the Gulf—particularly when combined with free zones in Dubai and Abu Dhabi—inevitably heightens the risk that capital of opaque origin may circulate through art. The positioning of culture as a sphere largely exempt from financial transparency further renders these investments politically and economically problematic.

Invisible Labor: The Gulf Labor Coalition

One of the most visible critical voices raised against this gleaming façade is the Gulf Labor Coalition, which has been active since the early 2010s. Comprising international artists, curators, and academics, the collective seeks to expose the labor regime behind cultural mega-projects by drawing attention to the exploitation, poor working conditions, and systematic rights violations faced by migrant workers employed in the museums constructed on Saadiyat Island in Abu Dhabi. An open letter sent to the Guggenheim Foundation in 2010—supported by more than forty signatories, including numerous internationally recognized artists—marked one of the first concrete steps in this critique, bringing the ethical responsibilities of art institutions in their processes of global expansion into public debate.

Reports published by Human Rights Watch since 2009 document recruitment practices that bind workers through debt, the confiscation of passports, precarious living conditions, and the effective absence of the right to organize. These findings move the Gulf Labor Coalition’s critique beyond isolated cases, pointing instead to a structural field of injustice.

In a context where art is routinely associated with universal values such as freedom and human dignity, the systematic rendering invisible of the labor behind these cultural structures sharpens the critique of art-washing. For the Gulf Labor Coalition, the issue is not limited to Guggenheim Abu Dhabi alone; rather, it raises a broader question about how globally expanding art institutions relate to the labor rendered invisible in the pursuit of architectural grandeur and cultural prestige. In this sense, the call for boycott becomes less a singular act of protest than a question addressed to the art world at large: why are the resources mobilized for the most advanced design, the highest budgets, and the most ambitious collections suspended when it comes to the living conditions of the workers who make these institutions possible?

Beyond the Glitter: Culture, Fractures, and Possibilities

Despite all these contradictions, the cultural transformation unfolding in the Gulf cannot be read solely as a one-dimensional field of propaganda. The museums, biennials, and art platforms established under state patronage also create, compared to earlier periods, expanded spaces of visibility for local artists and intellectuals. Paradoxically, structures built through top-down policies may simultaneously give rise to arenas in which critical thought and alternative narratives can begin to take shape.

Ultimately, the cultural legacy of the Gulf will not be measured by the architectural grandeur of its buildings, but by the extent to which these spaces allow room for critical inquiry and freedom of expression. In the period ahead, the central struggle will unfold between the state’s desire to control culture and art’s capacity to render social realities visible.

The Final Test: Aesthetics or Ethics?

The sustainability of this grand cultural dream will ultimately be determined not by aesthetic achievements alone, but by the test it faces on the grounds of financial transparency, labor rights, and fundamental human rights.