The recent ban on feeding stray animals brings into question Istanbul’s centuries-old tradition of coexisting with animals—a culture shaped by mancacılar, charitable endowments, travelers’ notes, and a vocabulary of mercy that has refused to disappear.

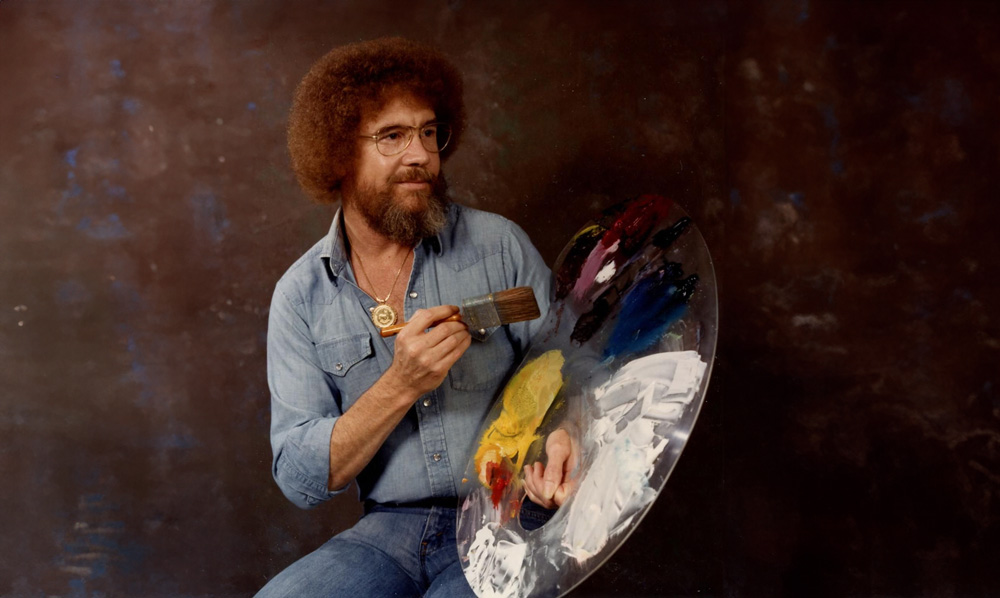

Imagine sixteenth-century Istanbul. The sun is setting in front of Şehzade Mehmed Mosque. Soon, a man carrying skewers of grilled offal appears, shouting: “Cat food!” Cats meow, dogs bark. This man is a mancacı—a street vendor who feeds animals. Today, however, Istanbul’s Governorship has issued a decision banning the feeding of stray animals around parks, schools, mosques, and religious sites. It is not merely an administrative act; it marks a rupture in a tradition of compassion that has endured for centuries.

The word manca derives from Italian and refers to food for cats and dogs. These feeders would buy liver, spleen, and hearts from butchers early in the morning, cook them, skewer them, and wander through neighborhoods carrying these offerings on their shoulders. Cries of “Dog food!” and “Cat manca!” were once an ordinary part of Istanbul’s soundscape. Some people purchased this food to feed animals themselves, while wealthier families hired mancacılar on certain days to ensure every animal in the neighborhood was fed. This was less a commercial exchange than a charitable act rooted in religious virtue.

The tradition was so established that it entered foundation deeds (vakfiye). Some specified that cats near mosques must be provided with liver every day. In Sultan Bayezid II’s foundation, bread was purchased not only for cats but also for dogs, and injured animals were to be cared for and treated.

European Travelers in Awe

European travelers were astonished. The German cleric Stephan Gerlach wrote that thirty to forty cats were fed liver daily in front of Şehzade Mosque, and that people saw this as an act of worship. Baron Wratislaw describes Turkish women extending meat to cats gathered along garden walls at mealtimes. Jean de Thévenot recounted locals building a small shelter from stones for a street dog that had recently given birth. Baron de Tott watched a man in a coffeehouse pay for all the liver and host a feast for the surrounding cats, wondering aloud if such a sight could ever be witnessed in Europe.

Antoine Laurent Castellan, writing in the early nineteenth century, observed:

“(…) Dogs roam the streets in packs, and woe to anyone who mistreats them! When a merciful Turk undertakes such a charitable act, men laden with meat walk surrounded by dogs and cats, distributing food to them…”

In the same century, Helmuth von Moltke noted that thousands of stray animals lived in Istanbul, sustained by bakers’ and butchers’ offerings as well as their own efforts—he even described the dogs as the city’s four-legged municipal workers.

Meanwhile, in Europe, the concept of animal rights scarcely existed. In 1821, a proposal in the British Parliament simply asking that horses be treated humanely was ridiculed. Yet in Istanbul, people regarded feeding animals as a daily civic responsibility.

The Ottoman Approach: Regulation, Not Prohibition

Public health was, of course, a concern in the Ottoman Empire. In 1887, a rabies treatment center (Dâülkelp Tedavihanesi) was established, and vaccinations were administered. Shelters were built for injured animals, and those who abused working animals were publicly shamed and punished. Problems were addressed not through bans, but through structure—and mercy.

The Mirror of a Civilization

Pierre Loti once wrote:

“I cannot imagine an Istanbul without dogs on its streets.”

Yet today, we are moving toward precisely the Istanbul he could not fathom. What is disappearing is not merely cats or dogs, but a city’s memory, conscience, and moral imagination.

History shows that this city once managed to live with animals—not despite them, but alongside them. What we need now is not new prohibitions, but a renewed moral order inspired by old stories of coexistence.

*This article is based on seventeenth- to nineteenth-century travel accounts, Ottoman archival documents, and Metin Menekşe’s academic study Osmanlı Medeniyetinde Hayvan Sevgisinin Mesleğe Dönüşümü: Mancacılık (The Transformation of Animal Compassion into a Profession in Ottoman Civilization: Mancacılık). Interpretations and narrative framing belong exclusively to ArtDog Istanbul’s editorial team.