The devastation in Gaza threatens not only every aspect of daily life, but also art and cultural heritage. The book Archiving Gaza in the Present records Gaza’s past while also archiving the cultural production that is continually re-emerging in the present moment. We spoke with Venetia Porter, one of the book’s editors, about Gaza’s rich artistic and cultural heritage, the act of archiving past and present on the brink of erasure, and the resistance embodied in the very act of making.

As destruction continues in Gaza with full intensity, cultural and artistic production about the devastation persists despite denial and censorship. The Istanbul chapter of the Gaza Biennale—also the cover story of our 30th issue—searches for ways of resisting destruction through art; meanwhile, the exhibition we refuse_d, curated by Vasıf Kortun and Nadia Radwan and recently held in Qatar, considers refusal as a potential for action, resistance, and repair.

One of the few new cultural and artistic initiatives to emerge in the face of the scale of devastation is the book Archiving Gaza in the Present. The volume brings together essays assembled with an archival impulse, focusing not only on genocide but also on the ongoing cultural and artistic destruction. Edited by Venetia Porter and Dina Matar, the book is a compilation of texts from a conference held in November 2024.

The book stands as proof that the perception of Gaza deliberately constructed in the West has no basis. The world may have heard of Gaza through the story of an Apollo statue, but Gaza had always been there, rich in cultural and artistic presence. Archiving Gaza in the Present not only documents Gaza’s disappearing cultural heritage and artistic production, but also draws attention to the ongoing acts of making in a city on the verge of annihilation.

Archiving is typically associated with preserving documents from the past; yet in a place like Gaza, where destruction is ongoing, it also means bearing witness to the present and safeguarding collective memory. Archiving Gaza in the Present is an interdisciplinary study that reconceptualizes this practice in the midst of war. We spoke with Venetia Porter about what it means to “archive in the present,” and how this becomes a practice of resistance.

How did you and Dina Matar conceptualise ‘archiving in the present’ at a time when the present itself was still unfolding and being constantly shattered by violence?

The book started with a two-day conference 30th November -1st December 2024. It took place a year into the war. We wanted to mark a moment in time by looking at how this unfolding genocidal war was affecting every aspect of life in Gaza. We found a range of speakers across disciplines – many from Gaza – and conceptualized this essentially in two main parts: the first engaged with topics from art, artists, art institutions, to archaeology, the built heritage, the museums and cultural centres, the second part looked at what we termed Memory and the Intangible, here we looked at the ways the destruction was being documented, the place of memory, the effect on education. We then asked speakers to engage with topics such as the law and its implications in regard to the destruction or the theft of heritage and what the future of Gaza could look like.

At the end of the conference, we realized that so important were the testimonies we were receiving across the two days, that we felt we need to record this – to ‘archive’ it by producing the book. The majority of speakers agreed to contribute and we also included some further contributions.

The book opens with the story of the Apollo statue, an incident that made many people aware of Gaza for the first time. What can we learn about the world’s selective attention to Gaza from this suspended space between legend and reality? In what ways does Archiving Gaza in the Present challenge or correct these fragmented and often mythologised global perceptions?

The world’s attention is indeed patchy in its focus. One of the initial reasons for organizing the conference was that we realized that what was not being covered by the media was the depth of the history of Gaza which we know about from both the archaeology and historical chronicles, its pivotal place in world history in ancient times, also the fact that there were 12 universities in Gaza with the level of education incredibly high, the major art institutions that existed where art students were mentored, where exhibitions were held etc. There are a significant number of artists in Gaza.

We decided at the outset that we should include as many images as possible. This way we could show a lot of before and after pictures which was important. This way, you could also see the willful nature of the attacks on mosques, museums – Jawdat Khoudary’s Mathaf, and the museums in Al-Qarara and rafah; cultural centres – such as the Rashad Al-Shawa centre, universities and libraries such as the Edward Said Library. It was clear to many of us that the erasure of heritage was deliberate. It was not enough to kill people and force them out of and then destroy their homes and neighbourhoods, but the very essence of what it is to be Palestinian – its cultural traditions and heritage, including its poetry (the deliberated targeting of poets) was being systematically attacked. This book is one way to confront the reality that there was – but still is – history, culture, identity in Gaza. This was not some kind of cultural desert devoid of art and creativity.

“Systematically Targeted”

There are significant numbers of artists in Gaza. At the outset, we decided we needed to include as many visuals as possible. That way we could show many crucial before-and-after photographs. You could then see that attacks on mosques, Jawdat Khoudary’s Mathaf, museums such as those in Al-Qarara and Rafah, cultural centers like the Rashad Al-Shawa Center, universities, and libraries such as the Edward Said Library were deliberate. For most of us, it was clear that the destruction of heritage was intentional. It was not enough to kill people, forcibly displace them from their homes and neighborhoods, and then destroy those homes and neighborhoods; cultural traditions and heritage—at the core of Palestinian identity, including poetry (with poets deliberately targeted)—were systematically attacked. This book is a way of confronting the fact that history, culture, and identity exist in Gaza—and still continue to exist. This is not some kind of cultural desert devoid of art and creativity.

Many contributors describe the ongoing destruction as both physical and existential. How did you navigate the emotional and ethical challenges of documenting a heritage that was being erased in real time when working on this book?

I think that what is brilliant about the contributors who came from a number of different disciplines, many established writers and commentators is that they were being dispassionate, they were stating it as it was. For us, as editors, our job was to do the writers justice by giving them a further platform beyond the conference to articulate their ideas, we were not speaking for them – these are their own views. But beyond that we felt a moral duty to do the best we could for Gaza by covering such a wide range of topics.

What does archiving mean in a context where the archives themselves — museums, libraries and universities — are being bombed?

The notion of archiving, for us, goes beyond what is the traditional idea of archives as being something in a library. An example of this are the manuscripts that were in the Omari mosque. Mercifully at least they had been digitized as is outlined in the book but as part of this ‘archiving’ we see what these manuscripts – those that they have been able to rescue anyway – are like now – in shreds. For us, archiving includes the physical objects of course, but also includes the poetry, the personal testimonies. These are crucial for preserving the essence of Palestinian identity in every aspect from the tangible to the intangible. We recognize that this book is only a small contribution to the overall picture – there is no way we could be exhaustive. So by archiving we also mean recording. What we also wanted to do was to provide a lot of references, further reading in the hope that the book could spark interest and encourage the reader to do their own research.

The book powerfully contrasts images of Gaza’s heritage ‘before’ and ‘after’. As an art historian and curator, how would you interpret this rupture in the visual record?

It was important to us to show the before and after and yes the destruction is a major rupture. What is extraordinary, however, is the determination of the Gazans to rescue, to rebuild – this has after all happened to them before – not on this scale though. There are also a number of groups working to aid in the documentation, some remarkable individuals in Gaza itself and outside. What must have been intensely disheartening was to see the attacks on buildings such as Bayt El Saqqa, the Qisariya market and others which had only just finished being restored where there were collaborations between the amazing organization RIWAQ doing restoration projects with local organisations. The same for the archaeological sites where students were involved in archaeological projects such as the St Hilarion Monastery.

For the study of world art history/archaeology, because so much had been published on the ancient ports and sites, on the Islamic architecture, that despite the destruction these will continue to be integrated into teaching. As a curator, it is important to demonstrate this tangibly and I deeply admire the Musee d’art et d’histoire in Geneva and most recently the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris whose exhibition Trésors sauvés de Gaza attracted over 100,000 visitors.

“And Yet They Managed”

Several essays reflect on the vibrancy of Gaza’s artistic and intellectual life just before October 2023. What aspect of the creative resilience of artists working under siege struck you most?

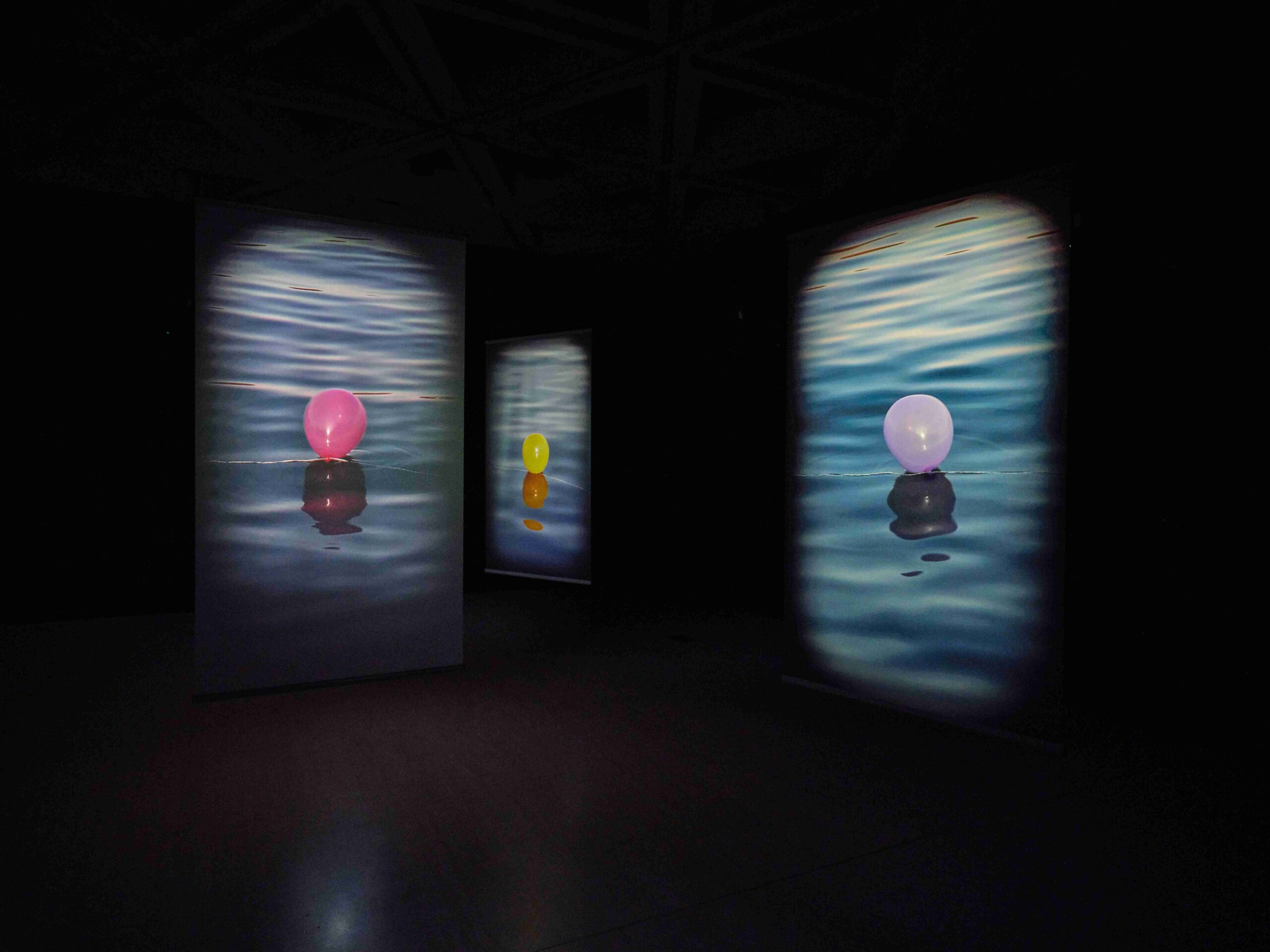

What struck me most was how the flourishing of art was down to a few key individuals who formed associations and collectives – Eltiqa and Shababeek for example. From 2005, Gaza was effectively under siege. It was extremely hard to get in and out, to get materials, to create exhibitions. And yet they managed and were incredibly resourceful. Numerous artists were mentored, organisations like the Qattan foundation, the French Institute helped; Darat al-Funun in Amman each year hosted workshops for artists.

It was Sarvy Geranpayeh, writing systematically about what was being endured by artists of Gaza who introduced me to the work of many of the artists who are in the book and I have been humbled by not only the quality of their work, but by their professionalism and generosity of spirit, sharing images of their work so willingly. You can see the new directions their work has taken since the war, often telling stories of their everyday lives. Several of them have turned their art to practical ends, working with children attempting to give them some respite from the tragedy of what they are having to endure.