Street art is not merely wall paintings made with a spray can; it redefines how one of humanity’s oldest forms of expression has been transformed in the contemporary world and how it renegotiates its relationship with society. From cave paintings to subway walls, from declarations of love to political manifestos, this article traces the footsteps of artists such as Keith Haring, Banksy, Swoon, and Miss Van, presenting the history, aesthetic power, and language of resistance that define street art. If walls could speak, today their language would be called street art.

History is most often written on palace walls. Yet sometimes the most truthful place to tell a story is that old, cracked wall in the middle of the city. That is precisely where street art begins: at the point where the invisible becomes visible, where silence turns into a scream, and where art blends not into museums but into everyday life. As sharp as the tip of a spray can, as clear as a stencil, as personal as a signature—yet at the same time, a collective memory.

From the earliest figures drawn on cave walls to today’s stencils, street art is the contemporary and political rebirth of humanity’s primal urge to narrate. This piece tells a story stretching from Cornbread’s first tag written in the name of love to Banksy shredding his own work in an auction room; from Keith Haring’s chalk figures in subway stations to Swoon’s portraits dedicated to victims of femicide; from Jean-Michel Basquiat’s rebellion on the streets to his ascent into museum walls. It reveals that art is not only an aesthetic concern but also a matter of resistance, representation, justice, and the pursuit of identity. Born from their traumas, cultures, and passions, these artists carve onto walls not merely images, but social wounds, suppressed voices, and calls for change.

From Cave Walls to City Walls

This journey, stretching from Stone Age cave paintings to Banksy, tells the story of how one of humanity’s oldest forms of expression has been reborn in the modern world and how it has transformed the art scene. Street art is not just images sprayed onto walls; it is also one of the most striking forms of social struggle, the search for identity, and democratic expression. With roots as old as human history itself, street art can be traced back to the first drawings on Stone Age cave walls. The 30,000-year-old paintings of the Lascaux caves stand as the earliest examples of the dialogue modern graffiti artists continue to forge with walls. One wonders: did that first “graffiti artist,” standing deep inside the Lascaux caves with primitive paint in hand, ever imagine that the hunting scene he painted on the wall would one day serve the same purpose as Banksy’s stencils thousands of years later?

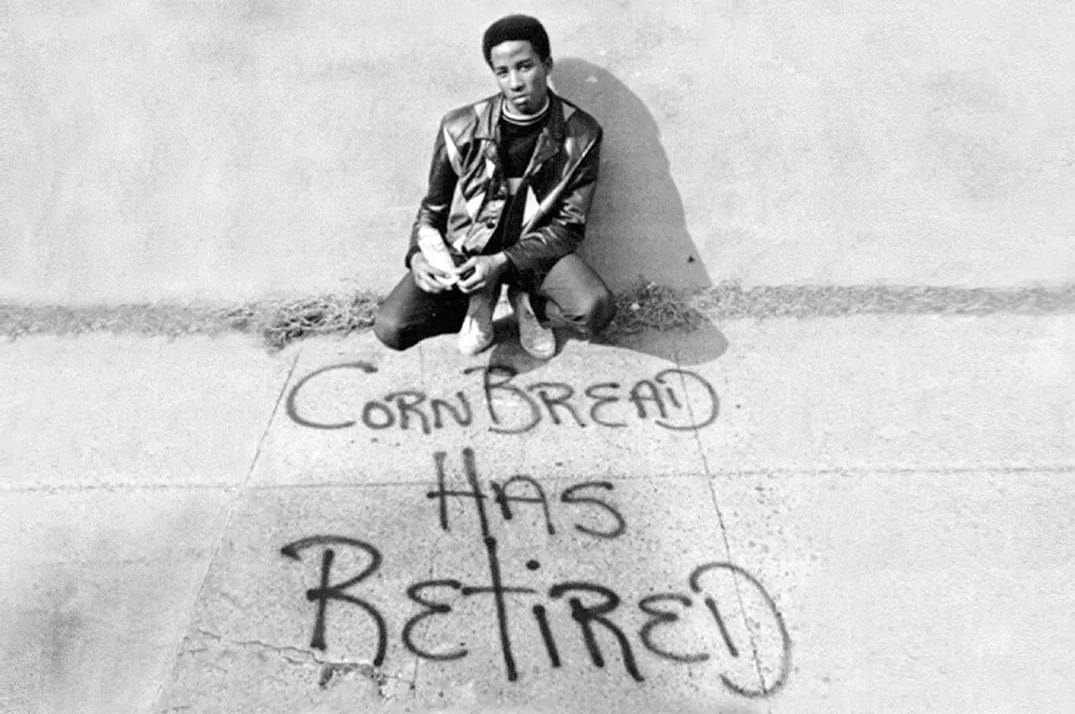

1967: Cornbread’s Love Manifesto

The efforts of a young man in Philadelphia to reach the girl he loved would end up changing the course of art history. Cornbread began by writing his name along his girlfriend’s bus route. A simple declaration of love ignited the spark of the street art revolution.

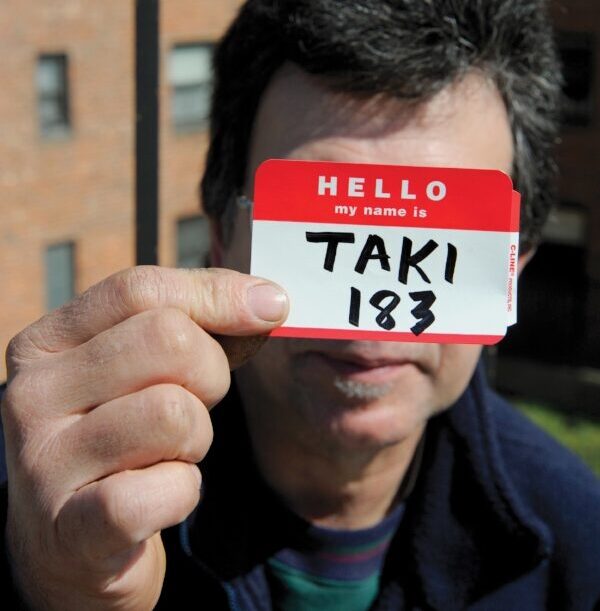

TAKI 183

Two years later, in 1969, TAKI 183 was leaving his tag everywhere he went in Manhattan, thanks to his courier job. This mysterious signature, spotted across all five boroughs of the city, soon caught the attention of The New York Times. In 1971, the article titled “Taki 183 Spawns Pen Pals” became the first media bombshell of street art.

Turning Point: Every tag TAKI 183 left behind carried a simple message: “I am here, I exist, you cannot ignore me!” And that is precisely what street art itself was declaring.

Keith Haring’s Journey of 5,000 Masterpieces

In 1980, at the age of 22, Keith Haring spotted a blank black advertising panel in the Times Square subway station. He rushed to the street, grabbed a piece of chalk, and made his first drawing. That moment marked the birth of one of the most democratic studios in art history.

For five years, Haring drew in subway stations every single day, producing a total of 5,000 works. His exclusive use of chalk, his choice to work in broad daylight, and his constant interaction with people set him apart from other graffiti artists.

“There is something very ‘real’ about the subway system. Perhaps there is no other place in the world where so many different people come together for a common purpose.” – Keith Haring

Ironic Truth: Haring’s subway drawings became so valuable that people began stealing the panels.

SAMO©: Philosophy on Manhattan’s Walls

In 1978, 17-year-old Jean-Michel Basquiat and 19-year-old Al Diaz began writing cryptic aphorisms under the tag “SAMO©” (short for “Same Old Shit”) on the walls of the Lower East Side—a neighborhood where rap, punk, and street art were fusing into the early hip-hop culture.

• “SAMO© AS AN ALTERNATIVE TO GOD”

• “SAMO© SAVES IDIOTS”

• “SAMO© AS AN ESCAPE CLAUSE”

These enigmatic messages caught the attention of the art world. When The Village Voice published an investigation in 1978 that revealed SAMO©’s identity, Basquiat had already moved on to the next phase of his artistic journey.

Basquiat became the symbolic figure of the transition from street art to contemporary art. His works tackled stark contrasts such as wealth versus poverty and integration versus segregation. Tragically, Basquiat died of AIDS in 1988 at the age of just 27. Yet in 2017, one of his works sold for $110 million, proving the immense power of street art within the art market.

The Banksy Effect: Anatomy of an Anonymous Revolution

Emerging from Bristol, the artist who has kept his identity hidden has become the most famous street artist in the world. Banksy’s power lies in his anonymity. Because his identity remains unknown, his messages resonate with even greater force. Using public space as his canvas, Banksy draws attention to issues such as war, poverty, and government corruption, compelling viewers to confront these problems within the fabric of their daily lives. His political views—anti-capitalist, anti-religion, and anti-war—are delivered with a sharp, ironic touch.

From Wall to Auction House

Banksy’s iconic work Girl with Balloon first appeared on London walls in 2002, etched into memory with the phrase “There is Always Hope.” In 2006, the artist gifted a framed version to a friend, which later came to Sotheby’s in 2018 and sold for £1,042,000. The true drama, however, unfolded the moment the auctioneer’s gavel fell: the artwork suddenly began to slide through the bottom of the frame, shredding itself before a stunned audience. Amid sirens and gasps, the piece destroyed itself halfway.

This act had been twelve years in the making. Banksy had installed a hidden shredding mechanism inside the frame back in 2006, anticipating the possibility that the work might one day appear at auction. Following the event, Banksy posted to Instagram, quoting Pablo Picasso: “The urge to destroy is also a creative urge.” With this, he openly defied the rules of both art and the market.

The message was clear: art cannot be bought.

The Irony: Banksy’s stunt, meant as a critique of the art market, paradoxically increased the work’s value by 18 times—turning it into the most expensive prank in art history.

Blek Le Rat

Blek Le Rat (Xavier Prou) was born in 1951 in Boulogne-Billancourt, a western suburb of Paris. During a visit to New York in 1972, he encountered graffiti for the very first time. Upon returning to Paris, he studied engraving, screen printing, and lithography at the École des Beaux-Arts.

The Rat Philosopher: In 1981, he began creating stencils of rats, which he described as “the only free animal in the city.” He used them as a symbol of an art form that, like the plague, would spread everywhere. His name was inspired by the comic strip Blek le Roc, while “rat” is an anagram of “art.” In 1991, he was arrested while recreating Caravaggio’s Madonna and Child. From that moment on, he shifted to working with pre-prepared posters.

Swoon

The American contemporary artist Caledonia Curry, known professionally as Swoon, was born in 1977 to parents struggling with opioid addiction. At the age of ten, her mother enrolled her in art classes for retirees. “Eighty-year-old retired painters adopted me, taught me how to paint. Thanks to them, I became a focused and confident artist,” she recalls. Today, Swoon is recognized as the first woman street artist to achieve international acclaim.

For the Victims of Femicide

Her 2008 work In Memory of Silvia Elena Morales addresses the wave of femicides that have claimed the lives of thousands of women in Mexico and Central America since 1993. During her visit to Juárez, Curry met mothers mourning their missing daughters as well as activists fighting for justice. She installed the portrait in Benito Juárez Square—where Silvia Elena is believed to have disappeared—four years later, in 2012, after escalating violence delayed the work’s placement.

C215, or Christian Guémy

A graduate in History and Art History from the Sorbonne, Christian Guémy takes his pseudonym from a prison cell. The turning point of his career came after his separation from his wife, when he created a stencil portrait of his four-year-old daughter, Nina. Since then, he has focused on portraying society’s forgotten individuals—the homeless, beggars, and refugees. In 2019, he was awarded the title of Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters).

Miss Van: Pioneer of Feminine Street Art

Vanessa Alice Bensimon, better known as Miss Van, began painting on the streets at the age of 20. She became known for the characters she called “Poupées” (dolls): sensual female figures with full lips, animal masks, and burlesque costumes that merge eroticism with innocence. Inspired by Frida Kahlo and Tamara de Lempicka, these figures often evoke vintage textures and a colorful atmosphere reminiscent of Romani folklore.

George Floyd and the Rebellion of Walls

In the summer of 2020, following the death of George Floyd, thousands of murals appeared around the world. Street art became one of the most powerful tools of protest and social change. This moment once again proved that street art remains the voice of the street.

A Language of Art That Spills Beyond Walls

The street art we can mention here only in fragments is today not merely a visual spectacle; it is a contemporary form of resistance that blends technology, activism, and the struggle for identity. Every figure, every layer, emerges not only as an aesthetic choice but as a visual manifesto of social justice, democratic participation, and cultural plurality.

Berlin’s East Side Gallery still bears the scars of the Cold War on its walls; once a wall of shame, it has become a symbol of peace and resistance. São Paulo hosts the world’s largest collection of street art, with massive murals reflecting the complex spirit of Latin America. Melbourne, with its officially protected graffiti laneways, declares that art can belong to the public. Istanbul, in turn, paints its multilayered past, fluid identity, and dynamic spirit in a riot of color stretching from Karaköy to Kadıköy.

Street art preserves one of the most essential aspects of being human: the courage to tell our story. Life, like art, belongs to the street.

This article has been compiled through research into various sources addressing the historical development and social impact of street art.