What are the increasingly frequent censorship mechanisms in the West regarding war and political uprisings trying to hide from view? When a stance is taken in the field of art, is it possible to stand up against these attitudes of disregard and rejection? The exhibition we refuse_d, opened at Mathaf (Alap Museum of Modern Art), brings these questions to mind. Bringing together the works of 15 artists, the exhibition questions the concepts of insisting, resisting, and creating under conditions of silencing, censorship, and displacement, while highlighting themes such as insistence, resistance, heritage, community, collective care, and restoration.

The exhibition features works by Taysir Batniji, DAAR (Sandi Hilal & Alessandro Petti), Barış Doğrusöz, Samia Halaby, Majd Abdel Hamid, Emily Jacir, Jumana Manna, Walid Raad, Khalil Rabah, Yasmine Eid Sabbagh, Nour Shantout, Suha Shoman, Dima Srouji, Oraib Toukan, and Abdul Hay Mosallam Zarara. We spoke with the exhibition’s curators, Nadia Radwan and Vasıf Kortun, about the exhibition process, its conceptual foundation, and its connections to the present day.

we refuse_d can be seen at Mathaf in Doha, Qatar, until February 9.

The we refuse_d exhibition draws connections to the Salon des Refusés and Hannah Arendt’s work We Refugees. In the exhibition, the concept of ‘refusal’ emerges as a political gesture, an artistic strategy, and a way of life. Why did you specifically choose these references? How did you approach these different layers while shaping the exhibition, and how do they reflect today’s realities of war, displacement, and censorship?

The exhibition developed gradually over time through discussions with artists, rather than following a master plan. We initially conceived the project as a “counter-exhibition,” inspired by the Salon des Refusés held in Paris in 1863, which featured important artists of Western modernism such as Gustave Courbet, Édouard Manet, and Camille Pissarro. The Refusés created a counter-narrative space against academic art, the classical canon, mainstream discourse, and the art market. We discussed the role of art and the Salon exhibitions of the time, how they followed power and the canon, and how today’s mega museum exhibitions and mega galleries collaborate with power, money, and dominant ideologies, failing to connect with society by choosing silence and neutrality. We then decided not to continue along this line. After examining the galleries in the region, we decided not to follow this line. There were two reasons for this deviation: First, the moral bankruptcy displayed by many Western states after October 7; second, we did not want the project to be tied to the Western art history canon. Our hope was that the artists would be public intellectuals.

“Over the past decade, more and more artists have been censored in Western countries due to their stance on conflicts, wars, and political uprisings…”

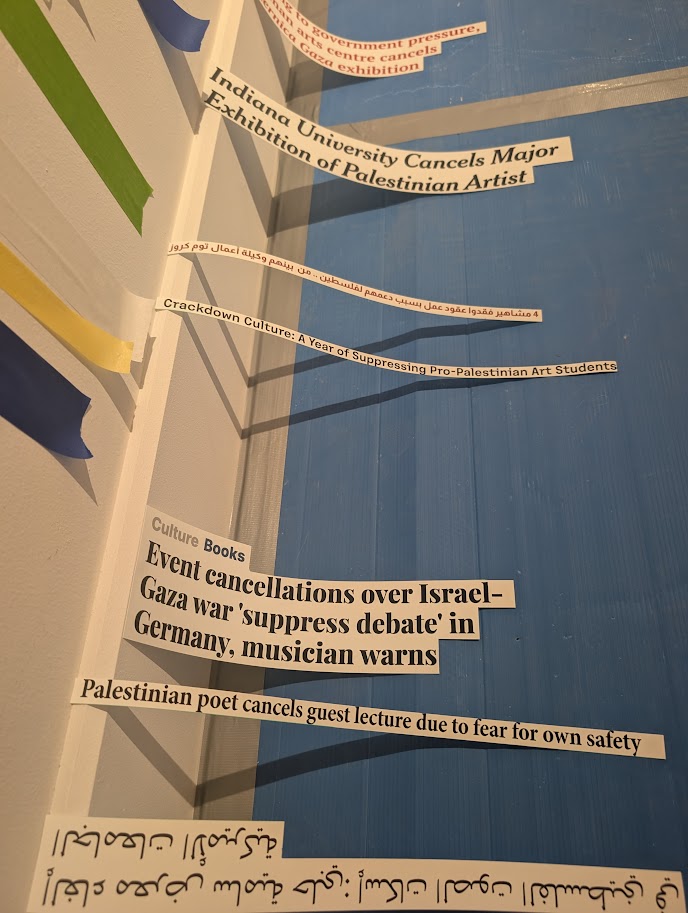

Over the past decade, more and more artists have been censored in Western countries due to their stance on conflicts, wars, and political uprisings, and artists have been excluded from art fairs, exhibitions, and public programs. More recently, in the context of the geopolitical division created by Israel’s genocidal war against Palestine, artists, academics, writers, and musicians have been canceled, censored, discredited, threatened, and faced financial sanctions. Academic institutions, news organizations, and cultural centers have been the most prominent implementers of suppression and blacklisting. In response, many artists have withdrawn from exhibitions and cultural events, putting their careers at risk. While for some, making art may be a way to resist emergencies, the trauma caused by losses can also lead to giving up on creating, researching, and producing intellectual or artistic work, or to not evaluating one’s capacities.

A reference to Hannah Arendt’s 1943 essay “We Refugees” provided a point of reference. We decided to approach refusal as a potential for action, resistance, and repair, and refusal in general as a way of demonstrating will. We decided to begin the exhibition with Samia Halaby and to revisit her canceled retrospective in some way.

We are living in a time of increasing censorship and polarization. Do you think curating could become a form of refusal, a way of resisting certain narratives or systems?

We believe it is crucial to defend the impact of the exhibition and to use its potential as a form of expression that is not reduced to impositions. Still, we must not be idealistic; the visible and invisible mechanisms that make exhibitions possible also determine the limits of what they can say.

“There are very few institutions in Europe that would support such a project, and none in the US.”

The exhibition presents art production as both an act of existence and resistance. How did you reconcile this defiant spirit with the institutional context of the museum?

First, there are very few institutions in Europe that would support such a project, and none in the US. Qatar was the right place in terms of its stance. Second, we must thank Zeina Arida, the director of Mathaf, for not allowing the institution to become indifferent. We are not being heroic, we are not taking a defiant stance. It might be more accurate to ask this question to many institutions around the world: “What did you do at that time…?” In Walid and Pierre’s installation, the vinyl wall text, pasted 50 times over and rendered unreadable, reads, “They told him that the institution preferred not to take sides.” Institutions are judged by their actions or inactions.

The exhibition spans from the 1930s to the 1990s and traces the continuities and changes in politically engaged art. What dialogues or encounters emerged between generations during this period?

Yes, there are artists from four different generations who, despite their different practices, are united in solidarity. Each may not be politically engaged; we do what we can with approaches such as protecting our mental health, promoting a sense of community, revealing different forms of expression through our practices, staying connected to our history, finding our place in history and keeping that place alive, and re-examining it through today’s lens. Taysir, Majd, Oraib, and Khalil strive to protect their own and their audience’s mental health. Nour, Abdelhay Mosallam, Yasmine, DAAR, Suha, Jumana, and Emily reach from individual history to social history to speak to the present. Abdelhay Mosallam, Jumana, and Oraib engage with poetry and writing. These are some of the threads that hold the exhibition together.

“We refused to design the exhibition in a way that would make the viewer a spectator of victimhood.”

Given the exhibition’s proximity to the ongoing genocide in Gaza, what kind of ethical or emotional challenges did you face while preparing it?

The exhibition was very intense—difficult moments to swallow, silent and visible tears, embraces. As a Turkish and an Egyptian-Swiss curator, we are on the sidelines; the artists have lived and are living this. It is best not to go into the details of the individual stories of loss; that would be pornographic and the work