In this selection, we trace the presence of dogs in the history of painting across a wide arc, from the “Cave Canem” mosaic of Ancient Rome to David Hockney’s Stanley and Boodgie. At times companions on the road, at times embodiments of a state of mind for artists, dogs bring the texture of everyday life and emotional depth into paintings.

As we trace the presence of animals in art history, we recently looked at the depiction of cats in paintings. This time, we turn our route toward dogs, one of the oldest and most deeply rooted bonds formed with humans. Our relationship with dogs is not merely one of domestication; it is a long-standing companionship established side by side within everyday life. Both humans and dogs are social beings with strong instincts, understanding the world through play and touch. Perhaps this is why they became two species that learned to read one another’s language most quickly.

For centuries, dogs have remained close at humans’ sides. They tracked prey during hunts, stood guard at doors, guided herds, and sensed danger in advance, carrying warnings. At times, without taking on any task at all, they comforted humans simply through their presence. Dog remains found alongside humans in archaeological excavations show that this closeness accompanied not only life, but death as well. This deep bond has been powerfully reflected in the art of painting. Artists have often treated dogs as figures that construct the meaning of a scene. They were carried onto the canvas as silent narrators of loyalty, waiting, play, or solitude.

As the poet Mary Oliver asks: “What would the world be like without music or rivers or the green and tender grass? And what would this world be like without dogs?” The dogs we encounter in paintings are like visual answers to this question. In this selection, we look at the visual history of a loyal and profound friendship between humans and dogs through dogs depicted across different periods that have left their mark on art history.

1. Cave Canem

Our first stop takes us to Ancient Rome, a context that allows us to think about the relationship between humans and dogs through myth, everyday life, and art alike. Even Rome’s foundational myth is marked by an animal’s guardianship: the story of Romulus and Remus being suckled by a she-wolf is an early indication of the meanings Romans ascribed to animals—particularly as protective and companion figures. This mythological backdrop situates the dog’s place in Roman culture not only in functional terms, but also within a symbolic framework.

The mosaic known today as Cave Canem dates to the 1st century CE and is located at the entrance of the House of the Tragic Poet (Casa del Poeta Tragico) in Pompeii. Buried under ash following the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE, Pompeii—and with it this mosaic—was brought back to light during excavations in the 19th century. Depicting a black dog chained by a collar, the floor bears the Latin inscription Cave Canem, meaning “Beware of the dog.” In Ancient Rome, dogs played an important role in hunting, guarding herds, and especially in securing homes. Large, dark-colored dogs were considered ideal guards: intimidating during the day and difficult to discern in the dark at night.

2. George Romney, Lady Hamilton as Nature (1782)

George Romney’s 1782 portrait Lady Hamilton as Nature depicts Emma Hamilton while also introducing a dog into the scene—a figure that draws attention with its small body, soft fur, and inward, penetrating gaze. At the center of the composition stands Emma Hamilton, born Emma Hart (1765–1815), one of the most striking figures of 18th-century Britain. Despite her modest origins, she quickly gained visibility within aristocratic circles through her intelligence, beauty, and theatrical talent, first playing a formative role in the life of Charles Greville and later in that of Sir William Hamilton, who served as Britain’s ambassador to Naples. In this portrait, Romney both idealizes and immortalizes a historical figure, while, through the presence of the dog, adding to the scene a sense of loyalty, companionship, and quiet intimacy.

3. Francisco Goya, El Perro (1819)

Francisco de Goya’s 1819 work El Perro (The Dog) presents one of the loneliest dogs in art history, etched into memory through its gaze. Now housed in the Prado Museum, the painting shows only the dog’s head; its body is lost within the emptiness that nearly fills the entire canvas. The dark, sloping ground in the foreground evokes either a mass into which the animal is slowly sinking or an ambiguous barrier behind which it has taken refuge. The upward-looking eyes convey a sense of waiting—one that seeks help but finds no response.

This painting belongs to Goya’s Black Paintings series, executed between 1819 and 1823 on the walls of his home during the final years of his life. Produced at a time when the artist was beset by severe illness, isolation, and psychological collapse, these images were not intended for a public audience but for an inward, private confrontation. El Perro stands as one of the quietest yet most devastating examples of that confrontation.

4. Sir Edwin Henry Landseer, A Favorite Greyhound of Prince Albert (1841)

Sir Edwin Henry Landseer’s 1841 oil painting A Favorite Greyhound of Prince Albert centers on Eos, the greyhound Prince Albert brought with him when he arrived in England. Entering British court life alongside Albert’s marriage to Queen Victoria, Eos is positioned in the painting as if guarding his owner’s personal belongings. Leather gloves, a top hat, and an ivory-handled cane establish a quiet order around the dog.

Renowned for his animal portraits, Landseer does more than merely depict Eos; he endows the dog with a stance, a sense of duty, and almost a personality. The greyhound’s alert posture recalls the place of this aristocratically associated breed within court life. The painting was given by Queen Victoria to Albert as a Christmas gift in 1841 and hung in the dressing room at Buckingham Palace. Later incorporated into the Royal Collection, the work was also exhibited at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition in 1842.

5. Gustave Courbet, Hunting Dogs with Dead Hare (1857)

Gustave Courbet’s 1857 painting Hunting Dogs with Dead Hare presents dogs not as domesticated symbols of loyalty, but as beings existing within the harsh reality of nature. In the forest, two hunting dogs stand over the lifeless body of a hare lying on the ground. There is no hunter, no weapon, no commanding human voice. The scene reads like a threshold moment in which humans have withdrawn, leaving the animals alone with their instincts.

Courbet’s dogs are neither affectionate nor docile. Their muscles are tense, their gazes severe—suspended between instinct, control, and waiting. The painter approaches the dog not as humanity’s faithful companion, but as an integral part of nature itself. It is no coincidence that the same dog figures appear in The Quarry, a deer-hunting scene Courbet painted a year earlier. Yet here, the absence of the hunter and his assistant renders the scene more striking; what remains are only the animals confronting death.

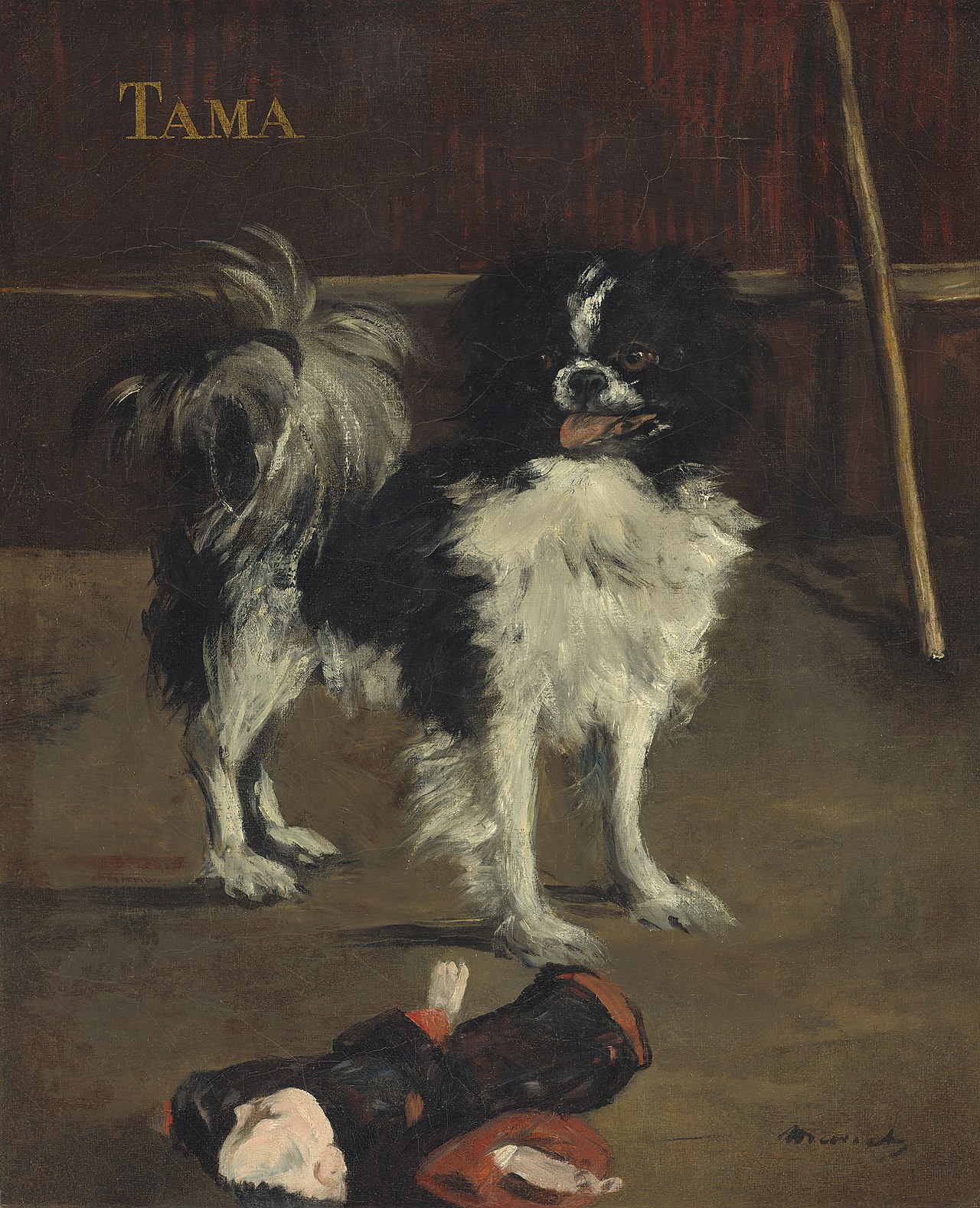

6. Édouard Manet, Tama, The Japanese Dog (1875)

Édouard Manet is regarded as one of the pioneers of modern painting in 19th-century Paris. His distanced relationship with academic painting traditions is evident in his tendency to bring everyday life and seemingly ordinary details to the center of his work. Tama, The Japanese Dog stands as a striking example of this approach.

The dog depicted in the painting, Tama, is a Japanese Chin. His name means “jewel” in Japanese. Tama was brought to France by Henri Cernuschi, one of the period’s prominent collectors. Manet portrays the tiny dog, its tongue slightly out, standing atop a Japanese doll—an image that indirectly reflects the artist’s interest in Japanese art.

7. Giacomo Balla, Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash (1912)

Giacomo Balla’s 1912 painting Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash presents the Italian Futurist emphasis on movement through an everyday scene. The composition features a dachshund on a leash and the feet of the woman walking it. Rendered with a blurring effect, the bodies of the figures appear as if they are in constant motion.

This work is directly connected to Balla’s interest in chronophotographic studies that examined the movement of animals. Developed from the 1880s onward by Étienne-Jules Marey, these scientific images made it possible to visualize motion by dividing it into temporal segments, opening up new expressive possibilities in painting. Rather than depicting a single moment, Balla brings successive phases of movement together on the same surface. Today part of the collection of the Buffalo AKG Art Museum, the painting is considered one of the early and influential examples of how movement was visualized in painting at the beginning of the 20th century.

8. Edward Hopper, Cape Cod Evening (1939)

The next work in our selection is Edward Hopper’s Cape Cod Evening. Painted in Truro on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, the work conveys the quiet of evening in front of a Victorian house. A seated couple outdoors and a collie standing close by form almost the only points of vitality within the scene. The dog’s body leans forward, its ears alert, its gaze directed toward the darkness surrounding the house, as if attempting to catch a sound not yet visible.

The dissonance between the house’s carefully maintained architecture and the formless grasses encircling it is striking. The couple’s plain clothing evokes the economic hardships of the late 1930s, while their inward, withdrawn postures further accentuate the distance between them. Hopper noted that the scene was not a direct transcription of a specific place, but rather constructed from sketches and impressions accumulated in his mind.

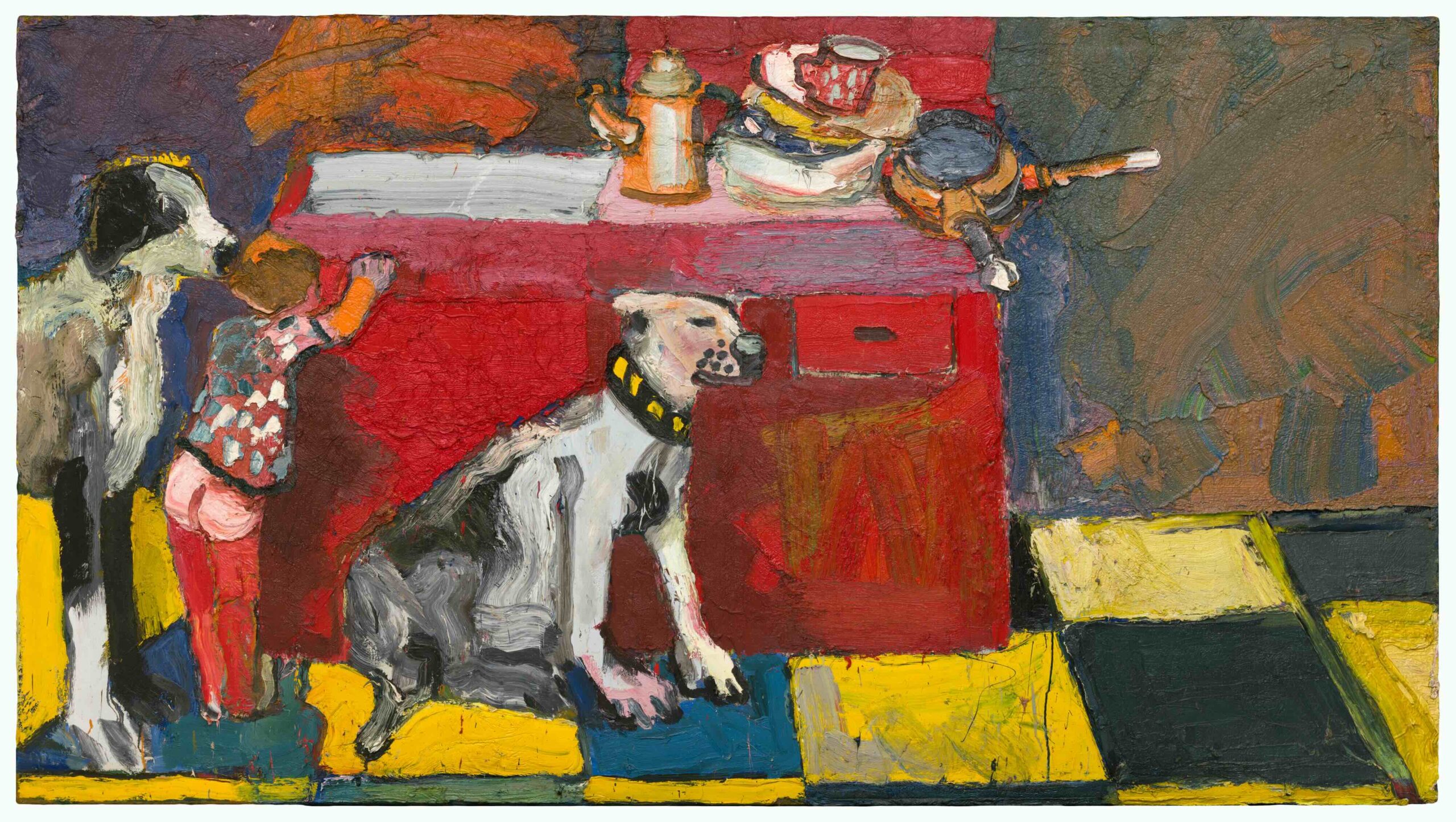

9. Joan Brown, Noel in the Kitchen (1964)

Joan Brown’s 1964 painting Noel in the Kitchen is among the most intimate examples of the artist’s autobiographical works centered on everyday life. A key figure of the second generation of the San Francisco–based Bay Area Figurative movement of the 1960s, Brown drew her painting directly from her own life. In this work, she depicts a moment from that life: her two-year-old son, Noel, shown in the kitchen, right in the midst of an ordinary instant.

As Noel reaches toward the sink, he appears to have lost his balance. His pants have slipped down, his body caught in motion. The floors are dirty, the counters cluttered with dishes. The scene does not present a staged or idealized domestic interior; on the contrary, it shows life in its messy, uncontrolled state. The dogs positioned on either side of the child stand almost like guards—alert and attentive, as if worried that he might fall or come to harm.

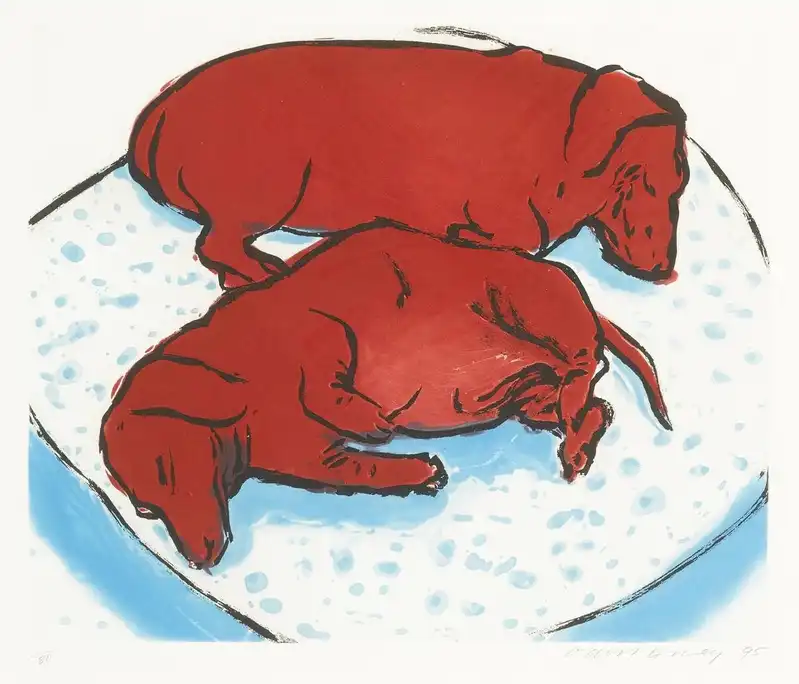

10. David Hockney, Stanley and Boogie, Horizontal Dogs (1995)

The final work in our selection is David Hockney’s 1995 Stanley and Boogie, Horizontal Dogs. The painting depicts the artist’s two dogs, Stanley and Boodgie, with whom he lived for many years. Lying side by side on their soft, plush beds painted in red tones, the dogs are shown in a state of drowsy rest.

In the early 1990s, Hockney began to make his dogs the primary subjects of his paintings. From 1993 onward, he started depicting Stanley and Boodgie in their everyday domestic states; to do so, he spread his working area throughout different parts of the house, transferring to canvas moments of the dogs at rest based on direct observation. The works produced during this period take the form of a series documenting the dogs’ presence within the home, their postures, and their relationship to space. Hockney expressed the bond he formed with his dogs in these words: “I feel no need to explain the apparent subject. These two little, dear creatures are my friends.”