Hale Tenger’s exhibition Hale Tenger / Borders / Borders, on view at The Art Gallery of Western Australia (AGWA) until February 8, brings together works produced over more than thirty years. We spoke with Tenger about this comprehensive exhibition, curated by Rachel Cieśla.

How did the idea for the exhibition at The Art Gallery of Western Australia in Perth emerge, and what kind of working process did you have with the institution’s curator?

Curator Rachel Cieśla and I had never met before. When she contacted Galeri Nev Istanbul and wrote that she wanted to organize a comprehensive exhibition with me, it came as a surprise to all of us. Rachel Cieśla is the Senior Curator at the Simon Lee Foundation Institute of Contemporary Asian Art at AGWA. In Australia, there are other state museums named after regions, and AGWA is one of them.

We held our first meeting online in February 2022. She later came to Istanbul in September, and we had a long meeting in my studio. The preparation process continued until the exhibition opened in August 2025. During this intense process, which lasted more than three years, the conceptual framework and the selection of works gradually took shape. As in every curatorial process, there were additions and omissions along the way. Final decisions were influenced not only by the exhibition’s conceptual backbone but also by the budget. To fully grasp how bold and ambitious this exhibition is, one must consider the distance between Australia and Turkey. Three large-scale installations were transported from the Arter Collection in Turkey. Even the logistics of transporting these works involved extraordinarily high costs.

In this exhibition, the concept of “borders” is addressed in many dimensions through your works. How did you establish a connection between the geographical foundation of your practice and Australia?

The exhibition was realized with the support of the Simon Lee Foundation Institute of Contemporary Asian Art, established within AGWA in 2022. Under the leadership of Rachel Cieśla as Chief Creative Curator, this department focuses on contemporary art from Asia and the Asian diaspora that has often been overlooked.

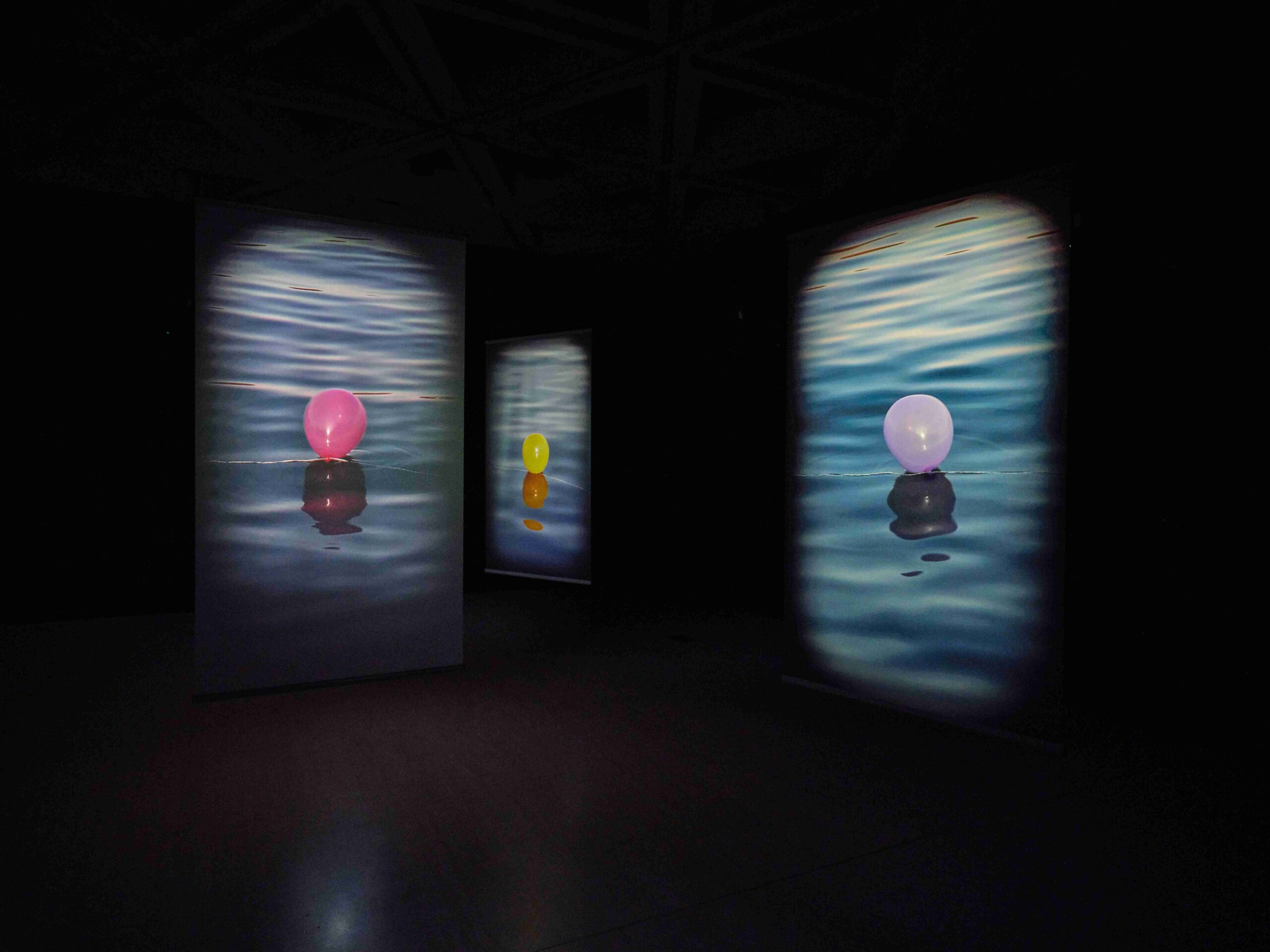

The selection spans a broad period, from the beginning of my practice to my most recent works. Rachel structured the exhibition around the concept of “borders,” encompassing not only physical but also political, mental, and emotional boundaries. The works are rooted in geographies centered on Turkey and the Middle East. Thus, the exhibition aims to establish a cultural dialogue between two geographically distant communities.

In her curatorial text, Rachel Cieśla emphasizes that your works “open up a space rather than offering solutions.” Do you think one of art’s responsibilities is not to provide definite answers but to encourage viewers to confront issues?

Rather than calling this a responsibility of art, it makes more sense to relate it to my own position. But yes—otherwise art becomes didactic and boring. For me, what has always mattered is creating a space that enables confrontation with existing realities and inviting the viewer out of passivity into an encounter where they question their own position and responsibility, becoming intellectually and emotionally involved. Definite answers often oversimplify complex realities. The transformative power of art lies in making space for uncertainty.

Hale Tenger / Borders / Borders is your most comprehensive institutional solo exhibition to date. It includes works from the 1990s onward, including the video Borders / Borders (1999). How do you relate the sand-drawn borders and children’s tug-of-war game in this work to today’s socio-political context? Has your perspective changed over 27 years?

It hasn’t changed at all. In fact, today we are witnessing how human-made systems such as colonialism and capitalism are leading not only to human collapse but also to the destruction of all forms of life on a planetary scale.

Themes of authoritarianism, militarism, and repression are prominent in this exhibition. Yet you seem to avoid direct slogans or explicit political calls. This tendency appears even stronger over time. How do you define this distance?

I began in the 1990s by producing works that conveyed their message directly, but this changed quickly after my first exhibition. Works that created more inclusive intellectual and emotional spaces became more prominent. In the 2000s, more poetic works emerged, though my harsher works never disappeared.

One of your most powerful works, I Know People Like This III, intertwines archive, body, collective memory, and trauma into a labyrinth. It reflects violence in Turkey and seems increasingly rare in institutions today. How did you balance “witnessing” and “self-protection” while producing it, and what was the emotional process like?

There were moments during the research process when I struggled deeply and even cried. Looking at over four thousand images of political violence in Turkey and later selecting about 700 of them was extremely difficult. Each image—some long embedded in my memory, others newly encountered—was deeply unsettling. When it was exhibited at Arter, I also witnessed strong emotional reactions from viewers.

In We Didn’t Go In Because We Were Always Inside / We Didn’t Go Out Because We Were Always Outside (1995), created for the 4th Istanbul Biennial, the tension between “inside” and “outside” is very strong. Do you think this work has transcended the Turkish context?

Yes. Its presentation at AGWA, as well as at Protocinema in New York and the 6th Ural Industrial Biennial in Yekaterinburg, allowed it to absorb the political and cultural conditions of each location.

You have previously produced works addressing conflicts in troubled regions, such as Beirut(2005–2007). Your installation Better Open My Heart Than Remain in the Comfort of Indifference (2024), first shown in Greece, explicitly references the genocide in Palestine. You addressed this directly in your opening speech. Was taking such a clear stance difficult? Did you hesitate? How was it received?

I produced this installation in the summer of 2024. Nearly a year later, in September 2025, an independent UN commission concluded that Israel’s actions in Gaza constituted genocide. People in Palestine are still being killed every day, including infants. The disproportionate use of force and disregard for international law concern the entire world. We must speak out—there is no alternative.

Fear serves no purpose. As global citizens, we are witnessing a live-streamed genocide. In my opening speech in Australia, I emphasized our need to reclaim justice and dignity in the face of enforced passivity. There is strong support for Palestine in Australia. The installation received significant attention and very positive responses.

Sadly, last week Australia was shaken by a terrorist attack at Bondi Beach in Sydney. The only previous mass shooting in recent history occurred in 1996. One of the attackers was disarmed by a brave Syrian refugee, preventing further deaths. At the memorial, an elderly woman was forcibly removed by police for wearing a keffiyeh. She said: “I am Jewish. My family includes Holocaust victims. If there hadn’t been Israeli flags here today, I wouldn’t be wearing this keffiyeh.”

How did it feel to see works from such a wide time span brought together again?

Seeing my large-scale works from different periods together moved me deeply. It was also striking to see how many of them remain relevant despite spanning more than thirty years. It is sad that the issues I have focused on—power relations, violence, borders, belonging, fragility, and resistance—still resonate today. But unfortunately, that is our reality.