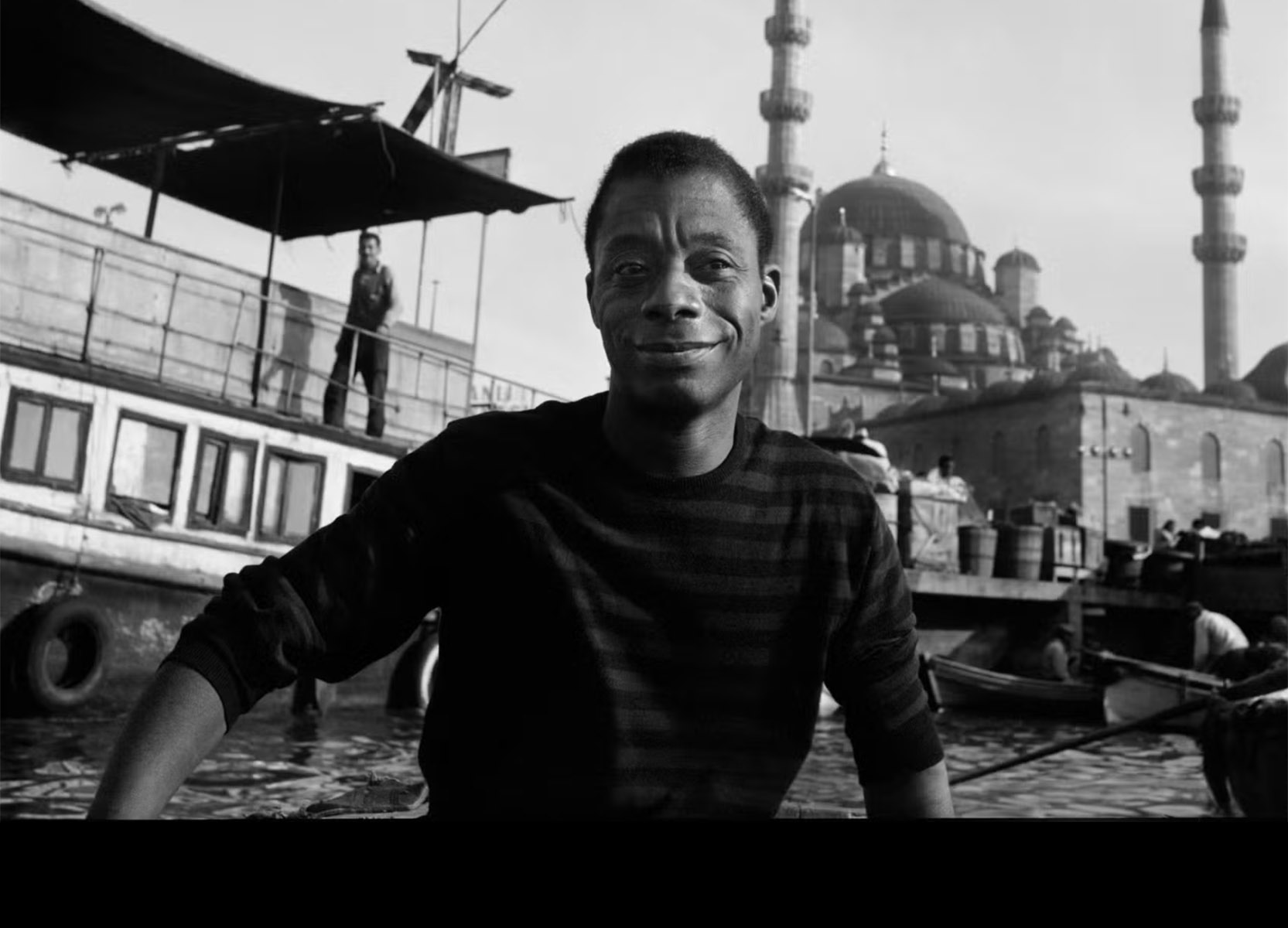

Had Turks truly been a loyal people in their bilateral relationships, perhaps there would have been no need for the saying, “Vefa is a district in Istanbul.” Unfortunately, apart from Pierre Loti, who wrote quite positively about Turkey, there is no foreign artist whose name or memory we have preserved, despite having spent long periods in this city. We have not named a street after Agatha Christie, nor after a High Renaissance artist like Gentile Bellini—despite his having lived here for sixteen months and even painted an oil portrait of the sultan. Adding James Baldwin—one of the most important American writers and activists of the 20th century—to this list of unfortunate omissions is especially disheartening.

Invited by his theater-artist friend Engin Cezar, whom he met in New York in 1957, Baldwin came to Istanbul in 1961, where he would live intermittently for ten years. He described the time he spent with intellectuals such as Gülriz Sururi, Yaşar Kemal, and Ara Güler as “the years when he was not demonized by society and did not live in fear of death.” He was not wrong: the 1960s went down in history as the darkest years for Black Americans. Three of his comrades in the struggle for Black equality—Medgar Evers (12 April 1963), Malcolm X (21 February 1965), Martin Luther King Jr. (4 April 1968)—along with many other Black revolutionaries, were assassinated one after another during those years by American intelligence.

“Istanbul Was a Safe Harbor for Him”

Magdalena Zaborowska, author of James Baldwin: Ten Years in Turkey, states that the peaceful writing environment Baldwin found in Istanbul enabled him to become productive again:

“Istanbul was a safe harbor for him. It provided the calm literary atmosphere he longed for. Think of Another Country. The manuscript had remained unfinished for ten years. In his letters, he mentioned repeatedly that he could not focus on the book. But just a few months after arriving in Turkey, he was able to complete it. Because he was in a new environment, people loved him and helped him. Istanbul became a refuge where he rediscovered his strength as a writer. Yes, Turkey was an exile for him, but above all it was an extremely productive stop in literary terms. At the same time, he was deeply nourished by the culture here.”

Born on August 2, 1924, from a one-night encounter of his mother, James Baldwin never knew his biological father. He took his surname from David Baldwin, the extremely conservative Christian preacher his mother later married, but he was in constant conflict with David—whom he simply called “father”—due to differences in lifestyle and belief. The person who first introduced him to literature, where he would find lifelong solace, was his elementary school principal, Gertrude E. Ayer. On her recommendation, he read Dostoyevsky and Charles Dickens, whom he admired throughout his life, and began writing short stories before the age of ten. During his high school years, poems he wrote were published in the school newspaper, which he also edited. Growing up in a family of eight children, economic hardship, the brutal racism of the country, and his questioning of his sexual desires were the primary factors that politicized Baldwin at such an early age.

After the war, in 1948, he went to Paris—where he would stay until 1957—in order to escape religious, sexual, and racial oppression and to broaden his horizons. There, he met intellectuals such as Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, and Max Ernst. However, Discourse on Colonialism, published in Paris in 1950 by Aimé Césaire, played a crucial role in freeing him from all his doubts. Through the concept of negritude he encountered in Césaire’s work, Baldwin overcame the inferiority complex imposed by being labeled a “Negro” and, like all Black people worldwide who internalized the concept, was able to decolonize his mind. It was in Paris—one of the two most important capitals of colonialism alongside London—that he fully grasped that racism was invented by Europeans to legitimize colonialism.

Aimé Césaire writes the following in this text:

“What Western whites could not forgive Hitler for was not the crime itself. The fact that Nazism had for centuries been inflicted upon non-European Algerian Arabs, the coolies of India (Indians enslaved and taken by the British to other regions of the world), and Black Africans did not disturb Westerners in the least. What disturbed them was not that the crime was against humanity, nor that human dignity was violated; it was that the crime had been committed against the white man!”

In an interview he gave in 1979, Baldwin articulated the consequences of this mindset with a foresight that still illuminates our present:

“It can be said that Palestinians have been paying the price of Europe’s moral crime for 31 years. It can also be said that the State of Israel was established not to save Jews but to protect Western interests at the gate of the Middle East. This might not have happened had the Third Reich never existed. As painful as it is, this is the truth. Although I was born into a world that believes in the Bible, I do not believe in the sections of holy books that concern the ownership of land. And Palestinians do not have to pay for the crimes committed by Europe.”

In my view, the most important characteristic of Baldwin—one of the greatest writers the English language has ever produced—was the courageous revolutionary stance he adopted in both his works and his personal life in the face of the sociopolitical conditions of his time. Alongside his powerful pen, his extraordinary oratory skills enabled him to win the admiration even of the most conservative audiences, making him one of the intellectuals most feared by the American state. As if the pressures he endured due to his political stance, his rebellious identity as a “Negro,” and his homosexuality were not enough, he grew weary of dealing with agents assigned to follow him by the state and chose to spend much of his final years in Paris and Istanbul.

Baldwin’s Istanbul journey began in 1957, when he met Engin Cezar—then in New York—after returning penniless from Paris, where he had experienced a rupture of consciousness. The two quickly grew close and rewrote Baldwin’s play Giovanni’s Room (YKY), which had been published a year earlier. Although Cezar was considered for the lead role, the play was never staged; nevertheless, this event marked the beginning of a long-lasting friendship. Alongside this intimate bond, the FBI agents who never left his side and the death threats he received were the main reasons Baldwin accepted Cezar’s invitation to Istanbul in 1961.

Baldwin as a Global Intellectual

Critics claim that during his time in Istanbul Baldwin made no effort to learn Turkish or to understand Turkey’s sociopolitical environment, arguing that his sole concern was America. Yet when one looks at the subjects he reflected upon and wrote about, it becomes clear that Baldwin was a global intellectual. His radical stance toward issues such as race, religion, colonialism, and gender—issues that continue to shape the global agenda today, including in Turkey, and which Baldwin personally experienced as traumas—proves that he was as universal then as he is now.

The house in Saint-Paul-de-Vence in southern France, where Baldwin died of stomach cancer in 1987, was placed under the protection of a foundation in 2016, and his intellectual and material legacy has since been compiled and transmitted to younger generations through residencies, seminars, meetings, and exhibitions. By contrast, despite Baldwin’s frequent presence in Istanbul between 1961 and 1971, it is striking that we possess very little information about this period—aside from a short film (From Another Place (1973), 12:03, Sedat Akay), a few photographs, and the letters he wrote to Engin Cezar (Letters to a Friend, YKY).

Yet is the fact that Baldwin wrote six books in Istanbul during this time not the clearest evidence of the productive bond he established with the city? Is it not a belated debt of gratitude for Istanbul to offer a museum/house that would preserve the intellectual legacy of Baldwin—a global public intellectual—in the city where he experienced his most productive years?