Dancer and choreographer Mihran Tomasyan has for many years been making a sustained effort to open space for a collective mode of production in which different practices come together. One of the key milestones of this effort is Çıplak Ayaklar Kumpanyası (ÇAK), which he co-founded and which marks its twenty-second year this year. We spoke with Tomasyan about the present state of dance through both his own productions and ÇAK…

How would you describe your relationship with the body and the language you create?

I can think about this question through my own choreographies as well as the collaborative works I take part in. I don’t have an approach like “I should make one piece every year.” Beyond my own works, I am involved in many different projects and I make a point of taking part in collective productions where hierarchies are more balanced. Producing within environments where such balances are observed motivates me.

When I look at works that stem from my own ideas—Sen Balık Değilsin ki, Sar, Hayat Ağacı, Tüh—I can see certain similarities and commonalities, yet for a while now I haven’t been producing something of my own. On the other hand, since recently I’ve been looking into various things beyond dance performance, I define this as a kind of “internal fallow period.”

If I were to answer this question by considering all my choreographic processes, I could say that I focus on “what happens in the moment,” and that each time I try to bring this forth. Sometimes I describe this state of happening-in-the-moment as a kind of rupture in time. I would call this a form of improvisation, but in fact I’m talking about an improvisational moment in which I know what I’m doing and where I’m going. With very small gestures, choreographic scores that keep alive the uniqueness of what is created in that moment are among the key common threads of my works.

I also place great importance on the relationship with the audience. I want there to be a connection between the world of the person on stage and the audience. This exists in almost all of my works. Rather than an approach that merely offers virtuosity to the audience, I try to create an affective space that draws them in.

Approaching Through My Identity as a Dancer

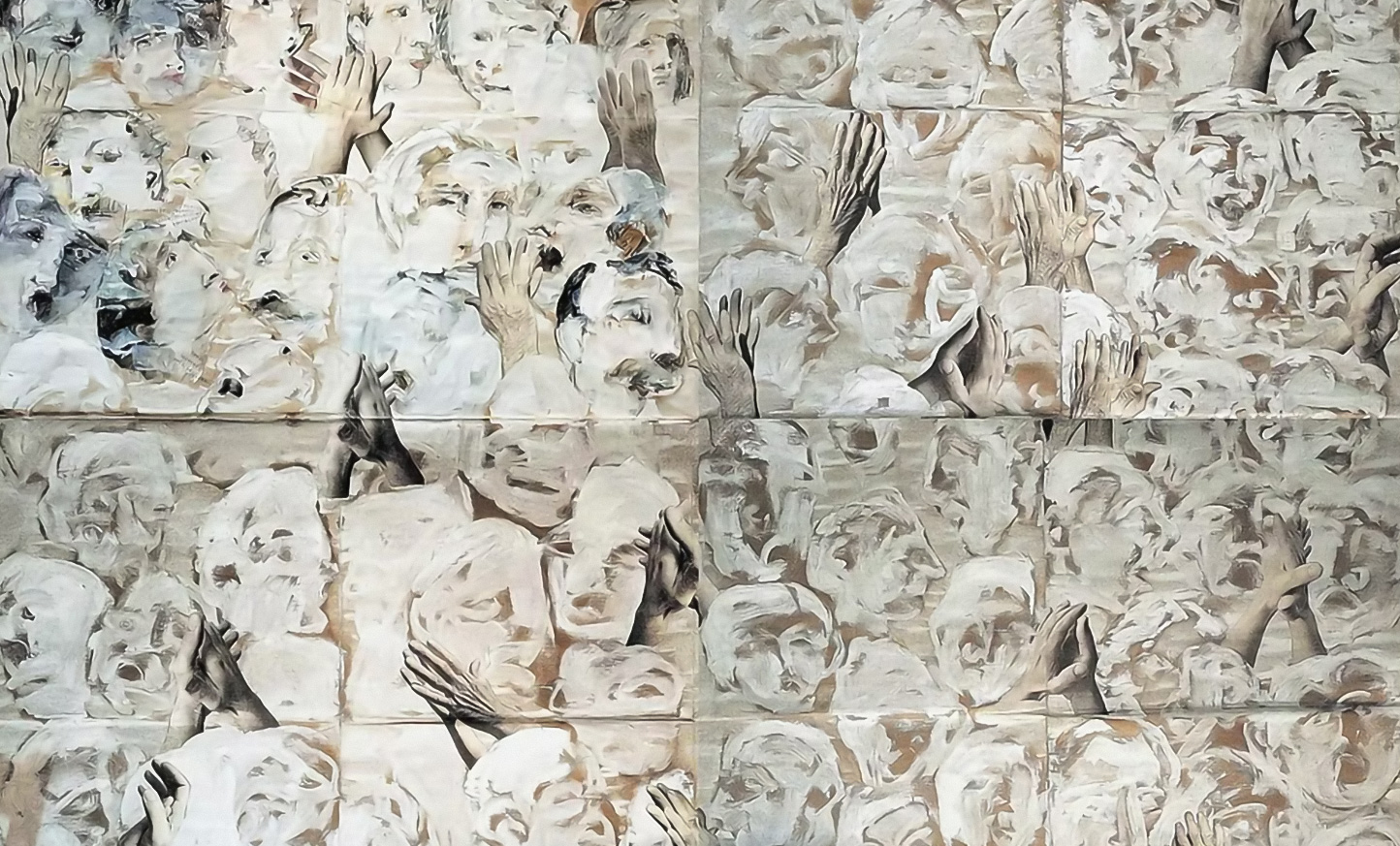

There are usually objects in my works. Pieces that consist solely of the body are very few. However, for example, in Yine de Kızgın Hissediyorum, performed with Sevi Algan, choreographed by Leyla Postalcıoğlu, and in which I took part as a creative dancer within the scope of Pelin Uran’s recent exhibition Gel kızgınları(nı/mızı) konuşalım öyleyse, even though there is no object, at a certain point in the performance I enter into states where I attempt to transform my body. In other words, my choreographies are often drawn toward similar concerns: continuous transformation, forcing something into a certain place, the transformation and deformation of an object—and, of course, of the body.

Physically, I am increasingly producing through an approach I call the “dancer’s mind.” It’s not just about movement; the creative dancer dimension of the work comes to the fore, and whatever the output may be—cinema, theatre, sculpture, music—I try to approach it with my identity as a dancer. I feel as though I’ve gradually moved away from technical dance, even though I actually enjoy practicing technical dance. But that requires a different kind of practice, and I no longer apply that practice in my life—and, in fact, I almost never really did. Maybe in my twenties. But I can say that I realized early on that that particular dancer’s discipline wasn’t suitable for me, and that I could generate disciplines of my own. I try to keep my body resilient through other means.

As a co-founder, Çıplak Ayaklar Kumpanyası has been part of many productions since the early 2000s and continues to be so. A great deal has changed since those days, of course. But when we look specifically at production practices and at dance, movement, and performance, what do you think have been the most fundamental changes?

As ÇAK, we are in our twenty-second year. There are four people in the core team, sixteen involved in studio coordination, along with our technician friends and volunteers—we are a large group in constant communication. The points where we come together are production, sharing, performance, a sense of home, and the studio; I think this is what keeps us standing. It has been this way since the studio opened in 2007. Periods change, but each time the studio continues to function like a small factory. When I think back to times when groups like Büyük Ev Ablukada and Gevende were also around, I believe we have a structure that adapts to each period in its own way. This definitely reflects strongly in the works.

In the 2000s, renting a stage and being able to perform were major issues. Because we couldn’t do that, turning this space into a performance venue, staging shows here for five seasons, and realizing that our pieces matured as we were able to perform them consecutively was extremely important. In our production practice, after performing a piece, we push ourselves to put it back on stage, then push again to do it once more… As we continue performing, the work begins to mature and gradually forms its own audience. I think this is also very valuable in terms of preventing works from disappearing.

“I Don’t See Any Progress in Türkiye’s Cultural Dynamics”

The fact that dance is still not programmed regularly creates disadvantages in producing works. Because there is no regular, continuous performance venue, long works cannot be produced. In the past, garajistanbul gave a great boost to this kind of production. There was dance in the venue every Monday and Tuesday for an entire season, and this continuity was very beneficial for the dance community and contributed to the formation of a dance audience.

When I look at Türkiye’s overall cultural dynamics in the context of changes over the years, I honestly don’t see any progress. There is not even the slightest movement regarding dance in the State Theatres or City Theatres; we usually speak only in terms of Istanbul… Of course, we can also include Ankara and Izmir, but across Türkiye as a whole, dance has a very small place within cultural dynamics. Fields such as dance and circus arts have not yet entered general cultural policy. For this reason, they continue to carve out paths for themselves in other areas.

Looking from a broader perspective, interaction in the world today is very different. Because dance has the potential to absorb all art forms into its own crucible, it can now enter museums and performances can take place in libraries. Dance is now an art form that is increasingly sought after for collaborative production with all other disciplines. I would say that in Türkiye we are at the beginning of this process. In this sense, there is also a side of these changes over the years that I view positively.

Dance is a highly collective process when we consider choreography as a whole. Yet, in another sense, bodily movement itself often feels very personal. What kind of balance or tension exists here? When producing a new work or performing on stage, how does this structure—both individual and collective—function?

I can answer this question with an example from cinema, a field I love working with. There, the most important figure is the director. I really enjoy serving a choreographer or a director. Ultimately, it is their world that emerges. For this reason, I try to keep my ego as much in the background as possible.

In artistic production where I am the author, however, I am more interested in horizontal hierarchical systems. I look at taking initiative, responsibilities, and how to work in a balanced way. When there are multiple minds involved in producing a work, a different balance emerges. With each new production, balances are established from scratch. Every piece creates its own dynamics anyway, and that’s when it truly has a different flavor.

In my own choreographies, I work extensively with outside eyes. I seek ideas from as many people as possible. I never keep my material entirely to myself. If I find something and feel an affinity with it, I try to confront it with as many people as possible—and this is very good for me. That’s why I’m willing to hear many opinions on the works I choreograph. Since I generally work in an abstract field, I strive for it to have meaning in the mind, to correspond to a feeling. For that reason, I try to understand what different eyes feel.

“The Field of Choreography Is Limited”

As a choreographer and dancer, how has your own approach and practice changed and developed over the years? What nourishes you—or what do you avoid?

Between 2000 and 2007, when I lived in France, I danced in many different places. One of the names I worked with was the choreographer Charles Cre Ange. It was very enjoyable… After returning to Türkiye, my desire to continue dancing was very strong. After all, I define myself as a dancer. However, there are very few people in Türkiye who are interested in technical choreography, and that field is limited. For this reason, and also because of my curiosity about composition, I leaned in that direction as well. Sometimes I wish I could just dance all the time…

On the other hand, as I mentioned earlier, instead of maintaining the practice required by technical dance, I try to keep my body active in other ways. I work in my family’s publishing house warehouse, for example—I carry books, or I always find something to carry, moving objects around the warehouse. In this way, I keep my body active while also trying not to leave behind the artistic production that comes with that practice. I think the emotional state in Sar, and the struggle with my Armenian identity in its subtexts, come from all this work of carrying books and objects in the warehouse.

In Taşıdıklarımız, the way Leyla (Postalcıoğlu), Berkecan (Özcan), and my ideas were structured by Francisco (Camacho, artistic director) was a similar process… All the material came from us, shaped through his guidance… As a dancer, I love making such works and thinking through them. Thus, while technical dance unfortunately fades away for me unintentionally and gradually, I continue to develop in the field of creative dance.

Over the years, my relationship with musicians at ÇAK has also grown immensely. Having a fixed space for twenty-two or twenty-three years, spending time with musicians and starting to produce things together, I have come to enjoy live music on stage so much that now, when I imagine the stage—or even my workshops—I always think of them together with live music.

In many works we’ve seen on stage in recent years, we more frequently encounter the coexistence of various disciplines. Technological and digital elements have also increasingly become part of these works. How do you approach this diversity?

If we start with digital elements: I prefer the more analog world. Digital frightens me. Or rather, I haven’t had long production processes with the people or teams who create such works. I haven’t been part of such a project. So for now, it’s not very much on my agenda. I place great importance on the production process as a kind of laboratory—on giving things time to truly mature.

We are living in an era where different disciplines produce together. Boundaries are very ambiguous. I like this. In general, in this internet age, everything is already intertwined, and I honestly enjoy that. I also think the possibilities where science intersects with art are important. I have no idea where all this will lead. But I am content with this chaos.

Istanbul is also a very chaotic city… To survive economically, you work on three or four projects at the same time, while also living within the city’s own dynamics. It’s a very different culture from Europe, with a different mode of production. This is something very unique. From this perspective, I find this chaos fitting for Istanbul. Istanbul in the 1990s was like this too… I think the dynamics of the city and artistic production are deeply intertwined. Perhaps the pressure created by the voids left by those who have migrated from here also plays a role in this dynamic. That, too, is a form of resistance, and all of these things are intertwined. That’s why standing side by side in this way feels exactly right for today.

Alongside Çıplak Ayaklar Kumpanyası, Tophane Noise Band is another collective you produce with. Could you tell us about that as well?

Tophane Noise Band is essentially a group of people interested in sound, initiated by Serkan Aka, made up of instruments created from mostly found objects with simple and clever interventions. It consists of me, Serkan (Aka), Selim (Cizdan), and Ufuk (Fakıoğlu). Berke (Can Özcan) also plays with us whenever schedules align, in keeping with the spirit of TNB, and supports us conceptually, giving us strength.

Tophane Noise Band flows a bit according to its own time… At the moment, we continue to perform the song Karargâh at Büyük Ev Ablukada’s Defansif Dizayn concerts, and this gives us immense pleasure. Suddenly, there are three thousand people in front of us, which is a feeling we don’t often experience in the performing arts.

We also have a few new works. One of them is Kapı. We created a simple setup using lavalier microphones attached to a house door, and we’re looking for a format suitable for playing at night. There will soon be a concert at Gizli Bahçe. This time we limited ourselves a bit—without dozens of instruments, just the idea of playing the door and being mobile feels very resonant after all that “carry–set up–play–dismantle” work. After the concert, we will present a more developed version in a performance at Arter in December.

Another area Tophane Noise Band is interested in is what we call “waste analog.” While making our music, we are experimenting with the idea of creating real video effects using our own found materials. Completely analog, handmade effects accompany the sounds simultaneously. This is also one of the works we aim to complete in time for Arter.

I know you’re in the middle of a very busy period. What lies ahead for you now and in the near future?

As ÇAK, we have new works we are currently working on. We’re making a kind of leap on our own scale. This is actually the first time I’m talking about it publicly. Beyond our internal work, there are dancers in their twenties who sustain the studio’s operations and work in the field of performing arts, and I think this represents a huge potential.

For many years, we also wanted to invite choreographers again. There are many precedents for this in our own history. At the moment, we are in communication with, and have confirmed, two choreographers: one is the French choreographer Charles Cre Ange, with whom we have previously worked twice; the other is Koen Augustijnen and Rosalba Torres Guerrero from les ballets C de la B in Belgium. In other words, we have plans to devote labor and time to different works in 2026 and to enter 2027 with new productions. We continue to produce.