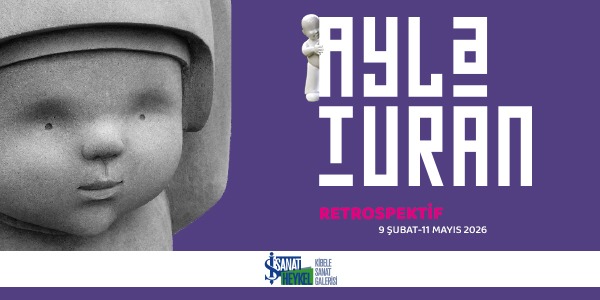

This interview consists of an unpublished recording made between Görkem Kızılkayak, founder of the Oktowallz Street Art Platform, and Arhan Kayar, one of the earliest and most formative figures in the history of street art in Türkiye. The conversation was conducted before Kayar passed away, but was never published.

At the time it was recorded, this interview was a current conversation. Today, it stands as a testimony. We had a long discussion with Arhan Kayar—whom we lost last year—about street art, public space, and projects that left lasting traces in the memory of Istanbul. We were planning a final reading for publication and talking about meeting again. That did not happen. We lost Arhan Kayar on 18 December 2024.

The interview you are about to read is one of the voices he left behind. In his own words, Kayar recounts what it meant to produce art in the streets in the early 1990s, when street art in Türkiye had not yet even been named; how Duyarkatlar, a public art project still referenced today, came into being; the days when İstiklâl Caddesi was closed to traffic for an art event for the first time; and the intention behind a wall work made in Istanbul in memory of Keith Haring.

This is not merely a “story of the past.” Arhan Kayar’s words remind us why street art does not fit into display cases, why it cannot be controlled, and why it is sometimes disturbing but always alive. They show how art in public space finds its way amid permits, obstacles, objections, and persistence.

The interview was never published.

But it was not lost. It now stands here, as it is, as a testimony.

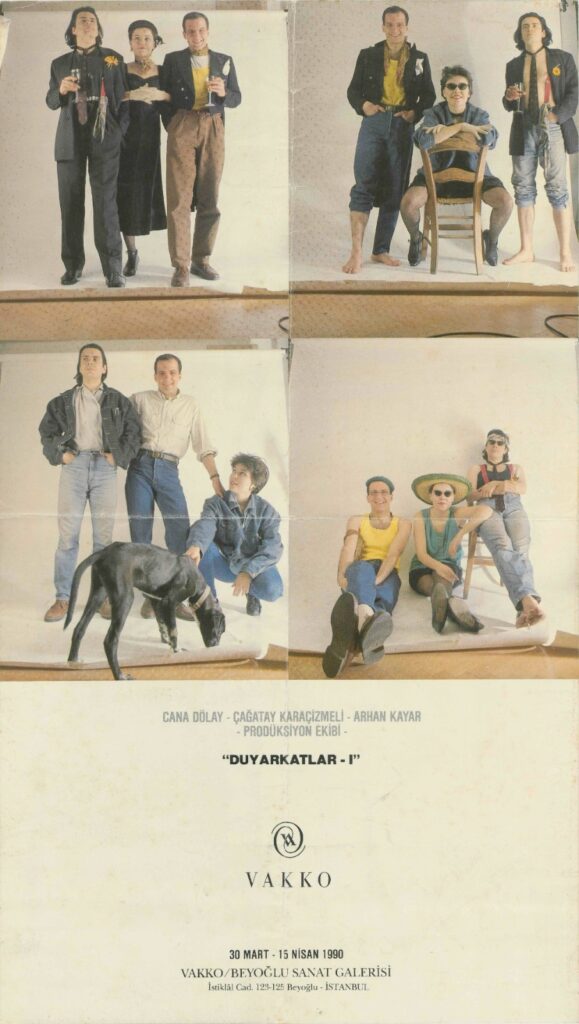

How did the idea for Duyarkatlar, which you realized with the same team after the Seratonin exhibition, come about?

The works we did in Seratonin 1 created quite a resonance. After the exhibition, Vakko Sanat Galerisi’s art director Gülçin Ülgezen and Vitali Hakko invited us to a meeting. During the İstanbul Film Festival (1990), they asked whether we would open a cinema-themed exhibition in their gallery on İstiklâl Caddesi. We said we could do it if we were allowed to use the building façade and the street as well.

At the time, Hilmi Yavuz was the head of the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality’s Department of Culture. We went to see our professor. He had already allocated the venue for Seratonin 1 to us. We told him that we wanted İstiklâl Caddesi—asking whether it could even be closed to traffic during the film festival. He thought about it, talked to the relevant authorities, and then said he could close it for four hours a day. He also said he could give us the street from 1 a.m. until morning for a week for preparation.

We painted film strips on the roads around the area where Vakko was located and the street where Emek Sineması was. We printed photographs of old cars onto metal plates and placed them within the film strips. When vehicles passed over them, they made sounds like “clack, clack, clack, clack.”

We created cut-out metal photo prints of film actors. We also wanted to do something around the word duyarkat, the Turkish equivalent of the photographic emulsion layer of film, and we did that as well—it attracted a lot of attention. At that point, all the shop windows along İstiklâl Caddesi told us to come and do something there too. It turned into a major event that spread across the avenue and lasted fifteen days.

At the same time, Pozitif had brought Sun Ra to Istanbul. We said to Mehmet Uluğ, let’s have Sun Ra travel down İstiklâl Caddesi on the back of a truck…

Coincidentally, just recently we hosted the Akbank Jazz team at Beşiktaş Belediyesi, together with the Pozitif team. They wanted to organize a concert at one of the municipality’s cultural centers. I asked them—partly to provoke them—you are the team that once had Sun Ra give a concert on a truck on İstiklâl Caddesi; why are you confining this festival only to indoor venues? They asked what I would suggest. I proposed Beşiktaş’s neighborhood markets, which host thousands of people every week. They declined, citing security and similar concerns. A few months later, they asked for another meeting. Afterwards, a nice concert was organized at the Saturday Market in Beşiktaş; moreover, they must have liked the idea, because street vendors were used in the festival’s promotional materials.

“Keith Haring for Keith Haring”

The Sun Ra concert attracted great interest. Then there was an empty wall opposite Emek Cinema. They asked us whether we would do something on that wall. Keith Haring had just passed away at the time. We interpreted one of his works and created a mural. We wrote on the wall: “Keith Haring for Keith Haring.”

Who painted it?

We drew it on paper first. Poster artists were working in the film industry. We did it together with them during the Istanbul Film Festival. The work stayed there until that wall was demolished.

You were probably one of the very few people in Türkiye who knew Keith Haring at the time?

Very few people knew him. A handful of Turkish artists who had lived in New York were aware of him. Even they did not accept Haring as an artist. One prominent writer even wrote, “They copied Keith Haring, this is fake.” We said: we did this consciously, in memory of Haring… Things like this are done around the world (laughs). Back then, people thought what we were doing was madness. Now, for example, they copy the installations from Seratonin. Even the artists who once criticized us are doing it.

While the term street art was not even used in Türkiye in the 1990s, you were already producing street art projects. How were you following what was happening in the world at that time?

My friends were going back and forth to Berlin and telling stories about the Berlin Wall. I was only able to go abroad after 1994. Until then, I couldn’t even get a passport.

The city is a very important part of human life, and streets also occupy a crucial place within contemporary art. Someone who uses the street is at peace with themselves. Of course, this goes back a long way—starting with murals in classical times and continuing to this day. But at the same time, graffiti emerged as a reaction, and there is also art installed in public space. For example, when we organized Istanbul Design Week, we created installations in streets and squares. We had certain designers and artists design objects and placed them in public space—in Karaköy, Taksim, İstiklâl Caddesi, in different locations. We actually want to continue doing that. Of course, the budget and the sponsorship system need to be figured out.

We prepared the Duyarkatlar project for Vakko and presented a budget to Mr. Vitali. He looked at the project. By the way, before the meeting, people told us, “Mr. Vitali won’t give you money, he’s very tight-fisted.” He said, “I’ll give you twice this amount; this won’t be enough.” He was such a wonderful, visionary person.

“There is life in the nature of this work.”

Türkiye discovered the power of art in public space rather late. Unfortunately, we still haven’t really discovered the power of street art. In recent years, the works that have made the biggest impact at the Venice Biennale carry the signatures of street artists like Saype and JR. Both of them came to Türkiye. Yet we don’t see street artists in the Istanbul Biennial program. Thankfully, there are a few street artists who manage to slip into Contemporary Istanbul. But they could only do so with their canvases. What do you think about this?

Back then, we were acting very freely. We didn’t even have a civil society organization behind us. Individuality is very important in the street. You can form collectives—but there are still individuals within them. The people who made Seratonin were individuals too. Some individuals and companies supported us. But we never issued invoices. We said, “We’re going to do this—can you pay for this part, can you take care of that part?” We worked with a different kind of logic, and everyone supported us a lot. Still, we went through serious financial difficulties.

After that, I returned to professional life. We founded a foundation called the Istanbul Art Promotion and Research Foundation. But the foundation also needed to find resources. The İSTAV Foundation still exists. To find money for the foundation, we became a company. You need to create specific funds for this and continue in a sustainable way.

Some building owners see street art on their buildings as dirt. For example, because Karaköy doesn’t really come alive at night, street art works there quite comfortably. But in other areas, they don’t like the artist’s idea, they don’t like the ideology, they try to have it changed. That’s a problem. And when the artist is restricted, they stop working. Because there is life in the nature of this work.

For instance, when we did a project with JR in Istanbul, graffiti artists added graffiti on top of some of JR’s prints. JR loved it. He said, “One of the greatest qualities of street art is that additions can be made on top of it. I had already taken the photograph after pasting them; I had achieved my aim. They were going to disappear over time anyway.”

Isn’t this precisely the most important difference of street art? Once the artist finishes the work, it becomes the property of the street. Could you share a bit more detail about JR’s project?

Inside Out was a global project. It had specific sponsors for production. There are also serious collectors of JR in Türkiye. One of them is my friend Fırat Gönenç. He called me and said, “You’ve done many projects in the city—can you help us?”

To do these works, we had to obtain permits. We needed to arrange cranes. There were many details involved. Then we selected the locations together. JR produced two large works inside the old shipyard. It turned out beautifully. I documented the production process. Over time, we became friends with JR’s family. We celebrated his sister’s birthday in Istanbul. Fırat arranged a boat. Afterwards, JR gifted me one of his prints.

JR chooses his subjects and locations very carefully. It can be difficult for JR to realize certain works here, because he mobilizes large crowds. There can be interventions during the permitting process or while the work is being produced. Even if someone from the street says, “I don’t like this,” authorities can step in and stop it. JR does not want to deal with that.

Did you realize other projects in public space?

For example, we organized pedestrian exhibitions. Artists produced works on walls, buildings, and the urban silhouette. We first realized this with Şişli Belediyesi, and then presented it to Beyoğlu Belediyesi. I participated as an artist in Şişli. The Beyoğlu project was curated by Emre Baykal and Fulya Erdemci. There was an infrastructure called the Istanbul Tourism Workshop, led by Tülin Ersöz. Together with them, we presented the project both to Beyoğlu Municipality and the Metropolitan Municipality.

In Karaköy Square and along İstiklâl Caddesi, some artists painted the pavements, some placed works on walls, some produced installations, others sculptures. As part of this scope, the cranes at the Golden Horn Shipyard were also painted.

Are there projects still waiting in the wings?

We have a land art project called Harran Earth Works. The renowned photographer Michel Comte said ten years ago, “I no longer want to take photographs; I want to work in art and design.” He wanted to realize a land art project in the Nevada Desert, similar to those at the Naoshima Museum in Japan—designing an underground, invisible space. I told him, “Let’s go to Harran together.” We went to Harran and found a stone quarry that is several thousand years old. Its name is Bazda; the quarry resembles a cave. We rented it for a while, but since this needed to be a long-term project, the continuation of the lease became an issue.

It is a very poor region; the district governorship is reportedly one of the most economically challenged in the country. They could only offer moral support. As a result, the project was put on hold for a while. We tried to secure funding from abroad, but the current war situation makes us uneasy. The site is only 12 kilometers from the border. We are talking about an area of one million square meters—the project is ready; we are waiting for the right conditions.

You’ve essentially created a massive rural development project through art.

We are waiting for peace to prevail in the Middle East before starting the project. We have invested a great deal of labor and money. In 2025, we would like to realize at least a happening there. Michel and I founded a design company in Zurich. Whatever the company earns, we will spend it on this project.

About Oktowallz Street Art

Oktowallz was founded in Istanbul in 2025 by Görkem Kızılkayak with the aim of making street art visible in public space and opening new fields of expression for creators. Oktowallz works not only with artists accustomed to painting walls, but also with creatives who have never touched a wall with a brush before, yet whose practices intersect with the street. By bringing together the artist, the audience, and the city, it seeks to make art a natural part of everyday life. For more information, you can visit its website.