Seyhan Özdemir and Sefer Çağlar are the protagonists of Autoban, a practice that made a significant contribution to Istanbul’s emergence as an international cultural attraction in the early 2000s, offering the city a distinctly original way of living. During that period and in the years that followed, Autoban consolidated its success by receiving numerous international awards, while its projects left a lasting imprint on collective memory.

Now entering their third decade, the duo have consistently positioned contemporary art as an indispensable element of the stories they tell—ranging from a hotel project in the Maldives to the recently completed Akbank Headquarters building; from the restoration of a fortress in Malta to the renovation of the iconic Hilton Hotel, one of the landmark buildings of the Republican era. Representing Türkiye at the London Design Biennale with The Wish Machine / Dilek Ağacı, they once again transformed a local idea into a universal narrative.

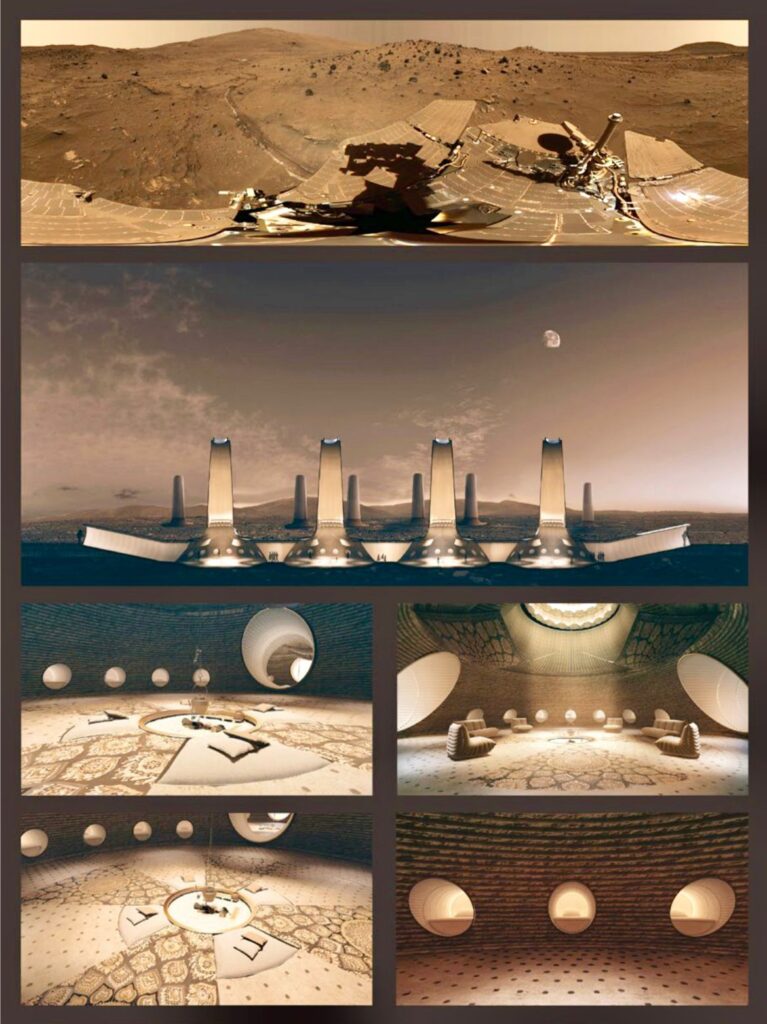

For Halil Altındere’s Mars Refugee Colony, Autoban proposed underground cities on Mars and urban forms produced through 3D printers by architects; with Taner Ceylan, they realized another poetic narrative—one that accompanies the artist’s intense imaginative world—at the Sipahiler Ağası Mehmet Emin Ağa Mansion.

As we conducted this interview, Mikla by Kısmet opened in London—bearing their signature.

“We usually work in collaboration with brands. We don’t see them merely as clients, but as partners with whom we embark on a long-term journey. What we do is not simply architectural design; it is about repositioning a brand with a five- to ten-year vision. Spatial design, for us, means creating an experiential field that tells the brand’s story. This is crucial, because the world has shifted dramatically. Everything has become digital; shopping happens in seconds with a few clicks. Yet despite this—or perhaps because of it—the value of experience has not diminished. On the contrary, it is returning. People want to engage not only with a product, but with the world of the brand itself. Space has therefore become a stage for identity. This was our approach with both Kısmet by Milka and Atelier Rebul: to express each brand’s unique experience through space.”

Does the rise of the digital world diminish physical experience, or transform it?

“I think it transforms it. Trust has become a central issue. People can no longer easily distinguish what is real and what is artificial. We are now in an era where artificial intelligence is actively shaping information—knowledge multiplies rapidly, but so does misinformation. That’s why physically encountering a brand, a person, or an idea has become far more valuable. Nothing can replace face-to-face contact.”

What are your thoughts on AI? As a designer, do you see it as a threat or an opportunity?

“Honestly, it’s neither entirely a threat nor entirely an opportunity. First of all, it’s evolving extremely fast—so fast that even the computers running these systems are struggling with energy demands. One of today’s global energy conflicts stems from this very issue. AI scans, aggregates, and recombines an enormous amount of information. But no matter how much it learns, the human factor is something else entirely.

We don’t feed solely on what we see or read; we also draw from our dreams, emotions, and intuitions. When I read something written by AI, I usually recognize it—because it lacks contextual grounding, an inner coherence. The same applies in our field. People say, ‘Designers are no longer needed; you type in a prompt and a space is generated.’ Yes, but that system only does as much as it has been informed to do. Humans add something from within; they bring an entirely different interpretation.”

So human creativity remains central for you.

“Absolutely. AI learns from us, but we also learn from it—it’s a reciprocal process. Still, creating something truly original remains in human hands. I’m not an expert, but I can say this: without emotion, creativity cannot exist. AI will become very intelligent—perhaps even ‘more intelligent than us’ one day—but it cannot replicate the human mind’s access to dreams, intuition, and storytelling.

Recently I saw a project where researchers reconstructed three-dimensional representations of Heaven and Hell as described in sacred texts. Even there, what we see is reproduction. AI doesn’t create something entirely new; it recombines existing data into a new composition. Maybe it will evolve into another dimension—perhaps even into something like the Matrix films we watched as children. But that doesn’t frighten me. Because the issue isn’t escaping; it’s being aware and continuing on your own path.”

What do you think about the relationship between writing and AI?

“I can still recognize AI-written texts. The way sentences connect, the placement of emotion—it’s different. AI can gather information, but it struggles to situate it within a meaningful context. The same applies to design: you can access every project and trend worldwide, but filtering that knowledge through your own lens and reconstructing it is another matter altogether. We don’t follow information merely to ‘use’ it, but to know it. Sometimes there are truly inspiring innovations—but unless you reshape that inspiration through your own perspective, it doesn’t become yours.”

So you don’t actively use AI, but you follow it.

“Exactly. We don’t yet use it to ‘design’ things directly. But we want to see its possibilities, to test its limits. We’re essentially asking: how unique can we remain? AI combines information to produce outcomes. We still position ourselves as humans—creative minds—somewhere else. At times, we use AI not to generate ideas, but almost as a way to step back and find our own path.

I’ve never had AI write a text for me. Sometimes I test it, just to see whether it knows a certain piece of information—but then I always verify it, because misinformation is widespread. So I’m cautious. Of course it will become much smarter. But we will too. This is a mutual evolution, and we’re only at the very beginning. It will transform us as well. In our field, design is often perceived as a kind of ‘visual shortcut,’ but it’s not. Design is a way of thinking. I see some astonishing visuals online—highly convincing, yet still no more than convincing. They lack emotion.

My 13-year-old daughter has been making incredibly creative drawings since childhood; now, what she produces with AI is astonishing. But that, too, will become commonplace—everyone will be able to do it. And then, to differentiate ourselves, we’ll return to that fingerprint. AI doesn’t threaten us in what we truly specialize in; it simply changes the way we observe the world. I’m not competing with it. I just want to remain aware—to know, but to keep walking my own path.”

From the early days of founding Autoban in 2003 to today, how would you define this journey?

“Back then, we didn’t sit down and plan to become an international brand one day—but we had an intense passion. Education matters, of course, but ultimately everything rests on personal dedication and effort. Dreaming, standing behind that dream, making the right decisions… Bringing all of that together isn’t easy. You may dream but fail to act; act but make the wrong decisions; or make the right decisions and still not get the results you hoped for. Together with my partner Sefer, we have always pursued that delicate balance.”

“The first ten years were extremely productive, especially in Istanbul. From the early 2000s until the Gezi period, the city was charged with incredible energy. International investments were increasing, and there were visionary clients. Our vision coincided with theirs. I often recall Frank Lloyd Wright’s saying, ‘A good project is made with a good client.’ It really was like that. Istanbul was a booming city at the time. We produced both interior architecture and architectural projects, and we also grew on the product design side. During this period, we participated in many international fairs, our designs received awards, and our work was featured in books and magazines. We were still in our thirties, but Autoban had already become an international design brand that had gone beyond Türkiye. People tend to see this as ‘luck,’ but I don’t think so. You open those doors yourself. Luck is the result of work, effort, and continuing to walk that path.”

How did your office culture evolve during this process?

“We were never ‘bosses.’ We were always people who worked together in the office. We had many employees, but no one ever acted as if they were above someone else. When I leave home in the morning, I still say, ‘I’m going to school’; I genuinely see the office as a learning space. This feeling has never changed.”

That decade was a defining period both for Istanbul and for you. You were among those who culturally transformed the city. How do you remember those years?

“At that time, Istanbul was not just a city, but almost a cultural center. For us, it also became a laboratory. The projects we carried out in relation to the city up until 2013 still define us today. We didn’t only create spaces; a way of life was also transformed. For example, House Café was a ‘lifestyle’ space within the Istanbul context; it offered people a different urban experience. Our book documenting the ‘first ten years’ was published internationally, entered Wallpaper’s selections, and was sold from Japan to Canada. One day, seeing my own book on the shelves of a bookstore in Japan was an incredible feeling. If the pandemic had not intervened, we would have published the second ten years as well. The first book was Istanbul-centered; the second would have told the story of our international period.”

How did the second period, post-2013, create a turning point for you?

“With that period, we truly transitioned into an international structure. Our product design brand grew; we collaborated with companies producing in places such as London and Lisbon, as well as across Portugal. Our products began to be sold in many countries around the world. This was followed by projects in cities like Hong Kong, Madrid, and Zurich. At this point, we are often asked: ‘How do they find you in such distant places?’ The answer is actually simple: when you do something good, you become visible. At that time, there wasn’t an environment where everything shone on social media as it does today. Promotion happened through books and magazines. As projects were published, new offers followed.”

“During this process, we designed Turkish Airlines’ legendary CIP Lounge at Atatürk Airport. This was a turning point for us. Projects followed this in Baku, the Doğan Group offices, and later other airport projects. The CIP Lounge received many international awards and carried us into infrastructure and large-scale projects.”

Amid so many large-scale projects, how did you preserve your relationship with art?

“Art has always been part of our work. Like a layer of emotion within modernism. Because we see architecture not only as a technical production, but as a way of storytelling. We have collaborated with artists for years. We try to leave ‘the trace of the period’ in our projects. I don’t define myself as an art expert, but I could be considered a small collector. The trace left by the artist inscribes the spirit of the time into the space.”

“We also try to guide our clients toward these collaborations. Because the story of a space is not completed only with furniture and walls, but with the artworks that exist within it. For us, this is a way of leaving a legacy.”

One of these collaborations was the London Design Biennale, wasn’t it?

Yes. In 2016, we were selected by IKSV to represent Türkiye. That year marked the very first edition of the London Design Biennale. The theme focused on the 500th anniversary of Thomas More’s Utopia. We asked ourselves: What is utopia? If the idea of “the best possible world” has not been realized for 500 years, perhaps we thought that our hopes have now been reduced to wishes.

We started from the concept of the “wish tree,” which is very common in Turkish and Eastern cultures—the tradition where people tie their wishes to a tree and send them into the universe. We asked ourselves how we could reinterpret this in a contemporary form. In the end, we designed a hexagonal system operating with pneumatic tubes. The hexagon—hexagon—symbolizes the “gate of heaven” in Eastern cultures. Through these tubes, people wrote and sent their wishes; no one knew where they went, but that sense of “the unknown” was part of its beauty. In our installation, figures such as the late Paul Macmillan, Zehra Uçar, and Koray Malhan were also part of the advisory board. This was very meaningful for us, because we had materialized the idea of “creating hope out of hopelessness.” I believe hope is one of the most important things that keeps people standing. Even in the darkest times, if there is hope for healing, life goes on.

So for you, architecture is always a form of storytelling.

Absolutely. From our perspective, architecture is a form of storytelling that is intertwined with life itself. Whether it is a gallery, a hotel, or a bank does not matter—the issue is to give that space a soul. Perhaps that is why Autoban was never seen as “just an interior design office.” We have always had a stance that is connected to art, culture, and people.

In a way, we opened a door. What an artist, a designer, or an architect does is exactly this: to bring to life what they feel, what they imagine. Sefer and I were young; we were imagining a different culture, a different way of life in Istanbul. We designed first for ourselves; later, those designs became the dreams of others as well.

Even in furniture design, we always tested things first in our own home. We asked ourselves, What kind of sofa would we want to sit on? What kind of space would we want to live in? For us, the issue was not only comfort, but combining the materials, craftsmanship, perspective, and aesthetics of the time. That is why, in our view, every product and every space carries a singular story.

What has working in different geographies taught you? Is every new project a research process for you?

Absolutely. Wherever we go, we first arrive as researchers. We cannot design without understanding the culture, history, rituals, and even the daily life of that geography. Building a bridge between the culture we work within and the culture we come from is the essence of our work. I felt this strongly on my first trip to Hong Kong. It was a culture I knew nothing about, so I first tried to understand the people—how they live, what they eat, what they read, their art. Because even two people looking at the same view can see completely different things; the real issue is being able to grasp that subjective perspective.

With every new culture we encounter, we are nourished both intellectually and emotionally. Being able to do this is a great privilege. Because every geography teaches us its own story, its own design language. For example, the wood carvings I saw in Asia’s tropical regions, especially in Indonesia, and the legends narrated through those carvings were incredible. For them, this is not merely a craft, but a way of storytelling through life itself. This intersects directly with our work. Everything is a story, really.

This perspective must also be reflected in your Maldives projects…

Yes, very clearly. For me, the Maldives felt like encountering the miracle of nature. On my first visit, I was fascinated by the power of nature and the way it renews itself. Even the formation of those islands is a lesson in itself. Think about it: corals gradually rise, then reach the surface of the water. Then birds and insects arrive, plants grow, and life begins. The entire ecosystem completes itself. For me, the real miracle is this: all of the structures we build there are covered again by vegetation within a year. From a distance, you only see a green island. This is a model where design does not compete with nature, but integrates with it.

One day, while walking on the island, I saw a coconut that had fallen to the ground. When we returned the next day, a sprout had emerged from it. A week later, it had almost become a tree. And all of this was happening on sand! We structured the projects accordingly: we placed the buildings around existing trees and did not touch very old banyan trees. We only relocated transportable species—that is, young coconut trees—to other areas. Then we reconstructed the texture, even adding new species on top of it.

Building in such a sensitive natural environment must not be easy…

Not easy at all. However, in the Maldives there are very strict conservation boards. You can think of them like the heritage conservation councils in Türkiye. They decide where construction is allowed around the islands—even down to whether piles can be driven into the ground. Especially the overwater villas are built on areas of “dead coral.” Direct contact with living coral is strictly forbidden.

Living within this system made me understand it much better. From the outside, it might look like “everyone is building hotels on the islands,” but the process is governed by very strict regulations. At first, I was skeptical too—I wondered, do they really protect it? But yes, they protect it very well. It’s hard to understand without experiencing it firsthand. That’s why the value of the work done there is very significant for me. Because what’s involved is not a struggle against nature, but harmony with nature.

Art was an important layer, wasn’t it?

Yes. In our first hotel project, we developed an art route together with young curators. Many artists from around the world were commissioned to create works. As you walk around the island, you suddenly encounter an artwork. We continued the same approach in our second hotel, Juweli Wing; for example, Seçkin Pirim’s large sculptural installation welcomes you as soon as you step onto the island. We are a very multidisciplinary, collaborative team. We enjoy producing together with different disciplines. Because for us, architecture is not only about “building structures,” but also about creating a story. The more people, emotions, and perspectives involved in a project, the richer it becomes.

Do your projects in Malta follow the same perspective as well?

Malta is a very special place for me. We are working on two hotel projects. These projects move Malta beyond being a conventional tourism destination. At the moment, we are working on the restoration of a fortress. It is a very old structure. Within the fortress, there are some circular-plan spaces; in fact, they were originally built for concealment. We are transforming these areas into “special experiential spaces.” In a way, this is about bringing the past and the present together.

History and nature seem to always coexist in your design approach…

Yes, absolutely. Because alongside human intelligence, the wisdom of nature is also incredibly powerful. The solutions each era developed in response to its own challenges are remarkable. From Göbekli Tepe to today, every period has produced solutions suited to the conditions it encountered. This, in itself, is a form of design. That is why I see design not only as aesthetics, but as a way of producing solutions for life.

The Hilton Bosphorus project is one of the important examples of modern architecture in Türkiye. What does working with this building mean to you?

Hilton was built in the 1950s by SOM (Skidmore, Owings & Merrill) and completed with Sedad Hakkı Eldem’s “local touches.” It is Türkiye’s first five-star hotel and also the place where international social life began. A place where Louis Armstrong gave concerts, where Elizabeth Taylor stayed, and where many major figures of the era visited. Therefore, it is extremely special both architecturally and in terms of cultural heritage.

The building underwent a renovation in the 1990s, but unfortunately the approach of that period altered it significantly. Instead of a modernist perspective, a style that I would almost call a “Grand Bazaar aesthetic” was adopted. Copper claddings and heavy ornamentation overshadowed the original design. When we started working on it, our decision was clear: this should not be a restoration, but a translation.

We are trying to understand the building’s DNA and the spirit of its era, and rearticulate it in the language of today. That is why we call it a “translation.” By preserving the elegance of the 1950s and the balanced simplicity of modernism, we are introducing a contemporary interpretation that also incorporates contemporary art. This is not just an architectural project, but also a transmission of heritage.

How did the story of this project begin? Were you invited, or was it through a competition?

Through a competition. Like the Akbank project, this was also an invited competition. We won the Hilton project, which was a great source of pride for us. Because it truly meant becoming part of a major legacy for Türkiye.

Considering Hilton’s place in the city’s collective memory, you must have taken on a huge responsibility.

Absolutely. This is not just a hotel; it is the memory of Istanbul. Our childhoods, our parents’ youth all passed through there. It is a structure embedded in collective memory. Our aim is to preserve this past while also reviving it with the spirit of today. By maintaining what I would call the “Republican elegance” of the 1950s, we want to carry it into the contemporary era. For this reason, we also included contemporary art in the project. Hilton’s story is like a “representation of a lost world,” but at the same time, it is a new legacy to be passed on to the future. I believe this is a valuable legacy for a country.

Turning to the Akbank project; what kind of transformation did you aim for there?

At Akbank, we carried out not only an architectural reorganization, but a cultural transformation. People no longer want to simply work in their workplaces; they want to enjoy themselves, to produce, and to connect with a brand they believe in. That is why the space needed to be rethought. In the new system, no one has a fixed desk. Employees can “book” any place they want. There are meeting rooms, Zoom pods, a library, sports areas, a spa, and even a clubhouse where talks are held. People both work and socialize there. This project was also won through a competition, and we have been working with Akbank for four years now. Works by Refik Anadol, pieces from Akbank’s own collection, and various installations have become part of this new atmosphere. With all these changes, Akbank has become younger and renewed. The “office” is no longer just a workplace; it has turned into an experiential space.

Was the aim of this transformation to rejuvenate the brand, or to change the way of working?

Both. One of the biggest challenges in the world today is human resources. People want to work not only for money, but in places that align with their values. In this project, we developed a strategy that “puts people at the center.” That is, we built a new face of the brand for those who work there, for third parties coming from outside, and for customers alike. Architecture here was merely a tool; the core issue was people and the sense of belonging.

How did the collaboration with Fratelli Rossetti begin?

When Fratelli Rossetti contacted us, they asked us to design a shoe. I wanted to create something I could call a “designer’s shoe”; I was thinking of a model that would provide comfort to a designer who walks 20,000 steps a day. Then some changes happened within the company and that project was put on hold. Instead, we worked together on a project for the shop window of their store at Via Monte Napoleone No. 1 in Milan.

Time was very limited, but we reinterpreted our own iconic products within the aesthetic of a resort collection. It coincided with the summer season, so we created an atmosphere parallel to Fratelli Rossetti’s resort collection. In the end, the result was an experience that aligned with the brand’s history and aesthetics, bringing architecture and fashion together. The following year, we also designed a display for Bisazza. We collaborate with major Milan-based brands, but we do this to expand the boundaries of our own design identity. These kinds of projects establish a shared language between us and the brand.

From the very beginning, you have consistently resisted being labeled simply as a “design office.”

We were never just a “design office.” We have always asked ourselves one question: “What kind of world do we want to live in?” In other words, we first construct our own vision. While living that vision, we reflect it onto people, brands, and spaces. That is what sets us apart. Every project is a story for us. Every geography, every culture, every client enriches that story. That is why none of our projects resemble one another. The only common point is this: we always bring together the materials, craftsmanship, technology, and emotion of the time. In our work, what ultimately remains is not just a building, but a story, an experience, and a trace.

In a time when the digital world is accelerating so rapidly, how do you see the future of physical space?

The value of physical contact will continue to increase. The digital world is fast, but nothing can replace face-to-face contact or the experience of being in a space. Trust, belonging, story—these are all made possible through physical space. Yes, artificial intelligence will become stronger, perhaps go much further. But originality still resides in humans, because it is born from experience, emotion, and personal trace. Even in a world where everything becomes virtual, encountering a space, an artwork, or a person in real life remains the deepest experience.

How would you define your relationship with the brands that choose to work with you?

We build long-term relationships with brands, not just project-based ones. Our aim is not to design a space, but to prepare that brand for today’s world and for the next 10–20 years. That is why we work not only in architecture, but also in positioning, experience, and strategy. For example, I sometimes attend a brand meeting not only as an architect, but also as part of a marketing or art discussion. Because all these fields are interconnected. Space is part of the brand’s holistic story. That is why we approach everything as a whole.

How does this approach reflect on brand identity?

The biggest difference is a “human-centered” way of thinking. People no longer want to just do a job; they want to build an emotional connection with the brand they work for and the space they inhabit. As in the Akbank example, employees want to be in places they enjoy, feel inspired by, and that align with their values. Therefore, it is very important to establish coherence between a brand’s identity and the language of its space. Another dimension of this approach is creative freedom. We always maintain open communication with our clients. In every project, we create a shared ground that brings together their vision and our experience. The best project is made with the best client—I believe that. Not luck, but mutual alignment of vision.

Your relationship with art within your projects has always been very strong. Why is this so important for you?

For us, art is not a luxury; it is a necessity. Because art is the soul of a space. You can complete a structure not only through architecture, but through art. Artworks add story to a space, define time, and carry the trace of an era. Even in today’s digital world, we believe that physical artworks are still extremely powerful. Digital production is increasing, but the trace left by a work created by a real artist’s hand is something entirely different. That is why, in our projects, we try to bring clients together with art and explain the value of artistic collaborations to them. In projects in the Maldives, in structures such as Akbank and Hilton in Türkiye, or in hotels in Malta, contemporary art has always played an important role. This is our way of creating a legacy: leaving “a trace that represents this era.”

Your way of working appears collective, despite the scale of your projects. Is this a conscious choice?

Yes, completely conscious. We were never “bosses.” We are an office that works together. Everyone in the office sits at the same table, within the same flow of ideas. When I leave home in the morning, I still say, “I’m going to school”; I like that state. Because that sense of “learning” keeps us alive. Every project is a learning process. New cultures, new people, new stories… I travel constantly; sometimes I change three countries in one week. But this is not exhaustion—it is curiosity. Because every new place teaches us something. We are people who work with curiosity.

How would you define your own creative process?

For me, creativity begins with intuition. You feel an idea not in the mind, but in the body. Sometimes it’s a smell, sometimes a sound, sometimes a dream… The source of creativity lies there. Then that feeling slowly takes form. Research, observation, cultural readings follow. Every project is a journey that begins with that feeling. In our work, it’s not about reproducing something that has already existed elsewhere, but about retelling the story of that place through your own perspective. That is why every project is unique. For me, design means “the courage to rebuild the world.”

Within such an international practice, what does Türkiye represent for you?

Türkiye is our root. No matter how international we become, everything started in Istanbul. The energy, cultural mixture, and productivity of that period are still with us. This place is still like a laboratory for us. We still draw inspiration from here. Because this city carries both Eastern and Western narratives. I have always believed this: no matter how far you go, your roots call you back. For us, Istanbul is that root. We translate the intuition we draw from here into other geographies. I think this is exactly where Autoban’s spirit lies: reaching a universal language from a local intuition.