Banu Cennetoğlu’s exhibition “neither carnation nor frog”, which opened on October 25 at Bursa İMALAT-HANE, unfolds as a research field unafraid of inconclusiveness—one that stretches from “the father” and its toxic inheritances to societal memory and impossible apologies. We spoke with Banu Cennetoğlu and Yavuz Parlar about the states of fatherhood, the ways knowledge is processed, and “nknk-erika,” the online journal that emerged as one of the outcomes of the exhibition.

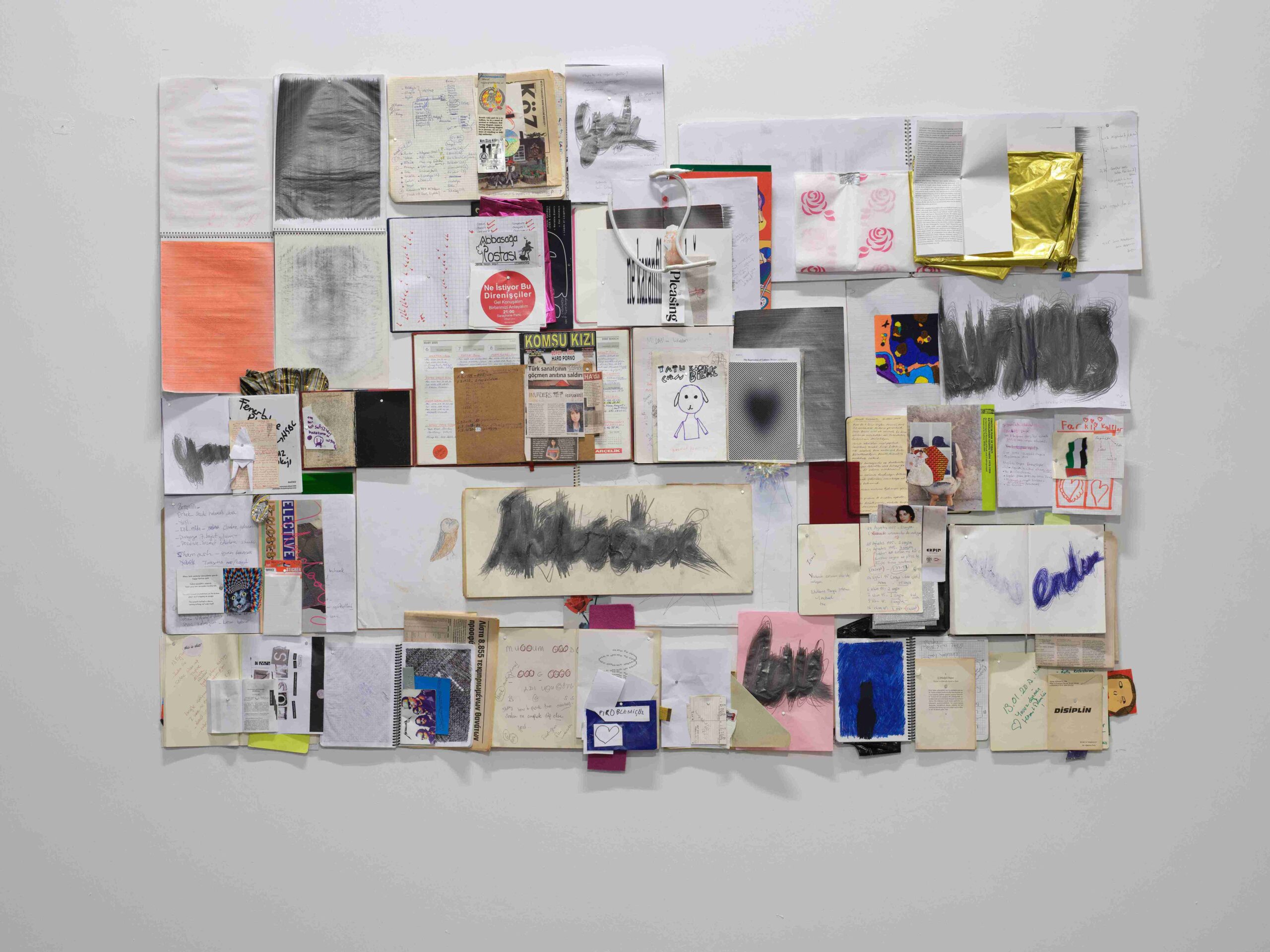

In neither carnation nor frog, Banu Cennetoğlu brings together the personal and the societal without ever stepping outside her artistic practice, weaving a multilayered language around concepts such as fatherhood, power, authority, and loss. Her works—ranging from books fragmented beyond function to lead weights, anonymous apologies engraved on zinc, and deflated and packaged helium letters—trace the marks of memory and guilt, and of wounds with little possibility of healing.

Meanwhile, the correspondence between the artist and the exhibition’s curator, Yavuz Parlar, is presented as an online journal that lays bare their entire intellectual process without self-censorship. We spoke with Cennetoğlu and Parlar about fatherhood, power, reputation, and denial, about the states of knowledge, and about how the exhibition process unfolded.

Fatherhood is connected to so many things. It’s as if one can trace the marks of a “father” everywhere. Both in the exhibition and in the text you composed with Yavuz Parlar during its preparation, the father—both within the family and in its broader forms—appears frequently. What is “father” to you? How do you interpret its toxic relationship with authority, loss, boundaries, and power?

Banu Cennetoğlu: If I begin from a personal place, I can roughly describe it as a state of haunting. Without disregarding those fathers and forms of fatherhood that can be otherwise, for me fatherhood—both individually and socially—has been a self-satisfied, self-assured, arrogant existence, grounded in the unquestioned “sovereign truths” of its own invisible book.

“Personally, the matter of the father had never been this visible until this exhibition—at least not with its name and form.”

Inevitably, sustaining this constructed and curated sense of certainty requires three indispensable ailments: power, reputation, and denial. A structure that cherishes, protects, defends, and spreads these; that excludes or punishes those who object; that seeks to “correct” others; that assumes it has the right to violate boundaries, legitimizing this with claims of acting “for their own good.”

But of course, no one can sustain this state alone. It is a spiral that those around—willingly or unwillingly, indirectly or directly—can support. Matters of loss and mourning make this spiral even more entangled.

Personally, the father issue had never been this visible—at least not with its name—until this exhibition. It had been, as I said, a sort of haunting—one that partly concluded recently. It is a mourning I began while he was still alive, I think. Yet the mourning I hold is not only for a father who could not be what he might have been; it is also for the individual and collective denials and violations that have embodied themselves in my father and in many other father figures. That’s why I believe it finds its place in the exhibition. As Yavuz also says, though our experiences of fatherhood are very different, we tried to look at the general state of haunting: how it circulates in spaces, objects, language, even silence—through whom and in what ways.

Let me end with the recipe we shared in our journal nknk-erika:

Eating the Father (serves 4, family size)

Ingredients

1 large father (bone-in)

2 tablespoons raw expectation

A pinch of guilt powder

3 liters family drama broth

A bit of inheritance (optional)

Preparation

-

Clean the father thoroughly; remove all heroism labels.

-

Place in a large pot, cover with family drama broth until submerged.

-

Sprinkle expectations and guilt powder, close the lid, and let simmer for years.

-

Once cooled, break into small pieces; blend if necessary (for easier digestion).

-

Serve with a side of “living your own life.”

Pro tips

Go easy on the salt; tears are salty enough.

Reduce portion size for children; it’s too heavy.

Do not refrigerate; once eaten, it disappears.

You’ve been working for years on how knowledge mutates, accumulates, and circulates. The exhibition ne karanfil ne kurbağa seems like an extension of this layered inquiry. Knowledge in your practice functions as a political matter, an ethical responsibility, and an artistic material. Where exactly does this concept sit for you?

B.C.: When I speak about my relationship with “knowledge,” I can say that it never rests in a fixed, clear place—nor do I want it to. As I take different positions in my practice, my relationship with knowledge shifts. This shift matters to me.

I look at the forms knowledge can assume—its mechanisms of production, classification, circulation, consumption, and its tangled relationship with representation. The question “for whom, by whom?” looks simple but tells us something clear about the relationship between knowledge—particularly that which presents itself as objective, rational, universal—and violence.

States of witnessing, the ties between knowledge, power, and denial, and the violence embedded in the practices of those who see or visualize… These have been long-term concerns for me—including my own position within them.

“Some things, I believe, must exist without ‘but’ or ‘however.’”

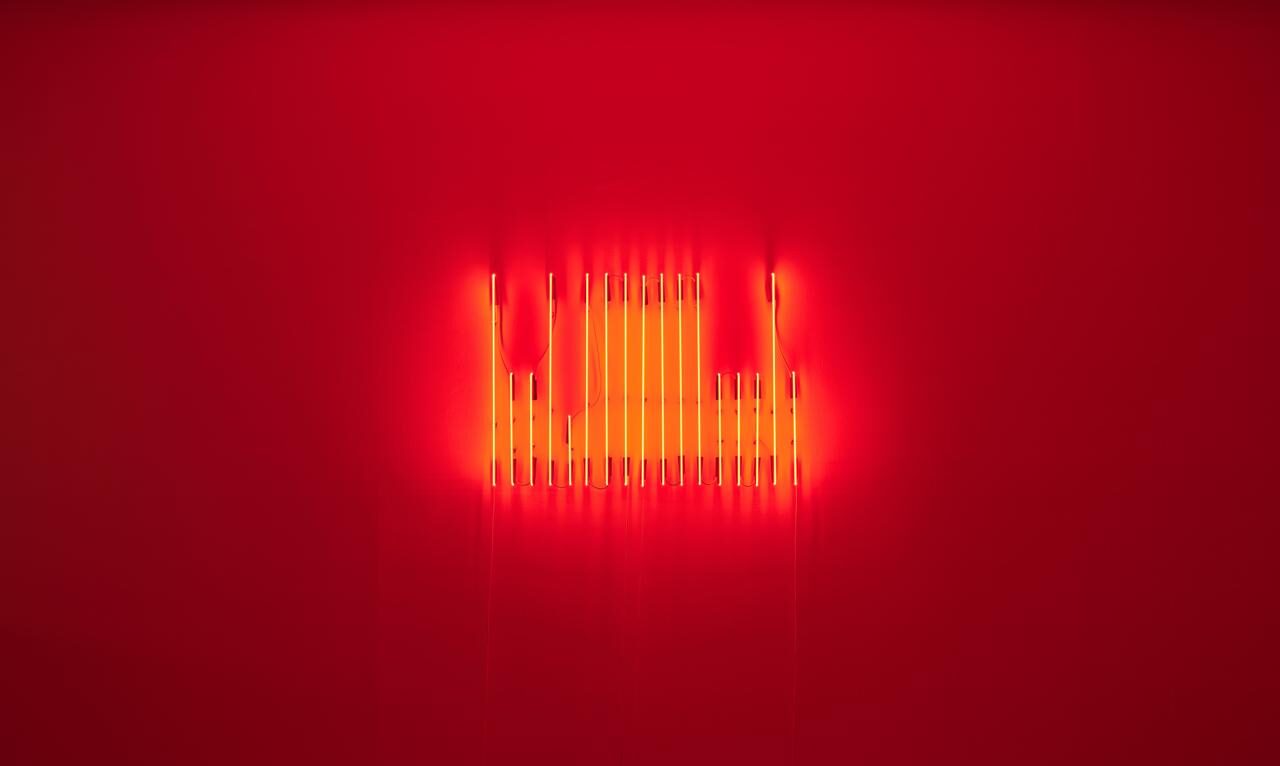

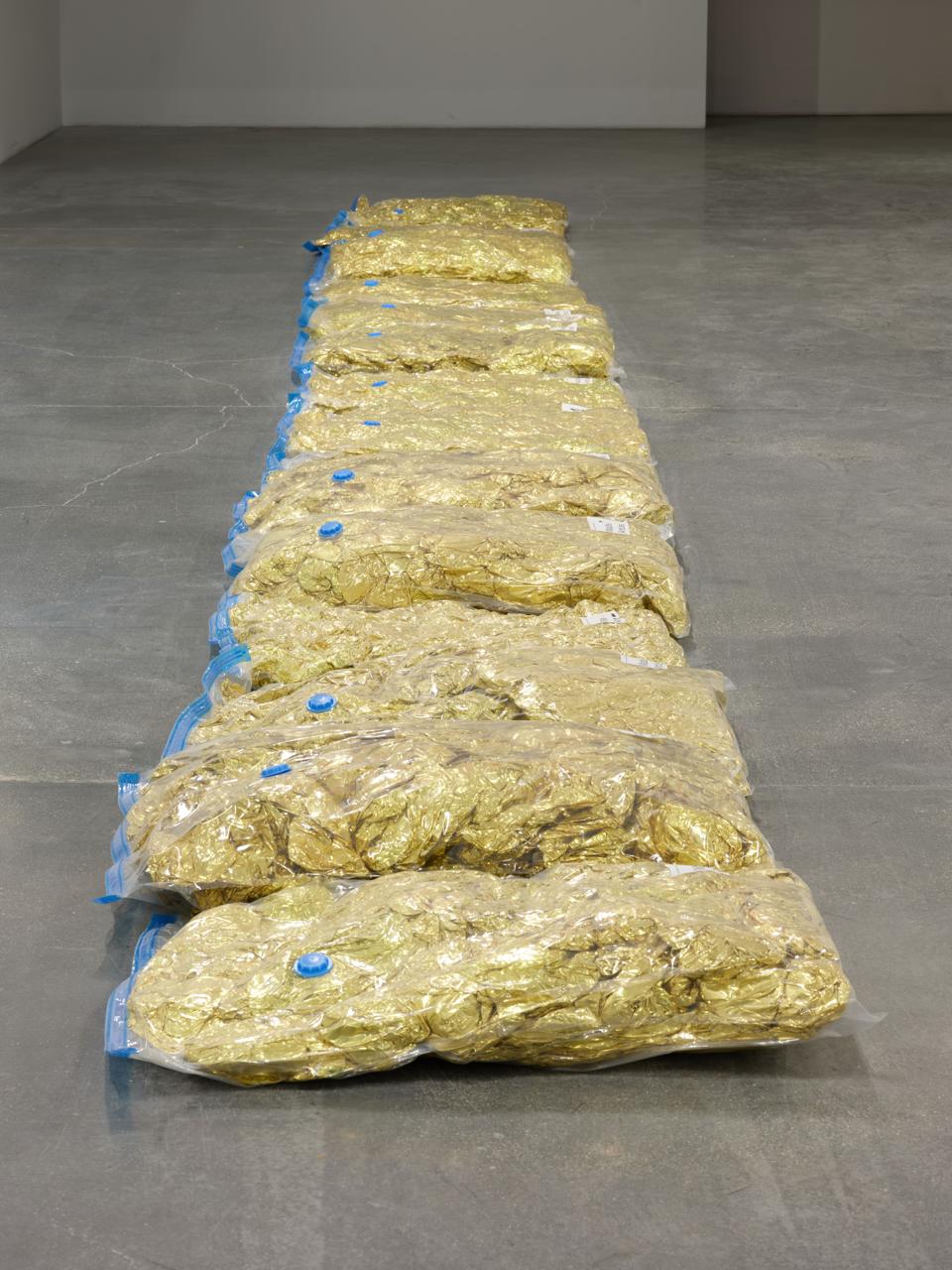

In 2015, using helium letter balloons for the first time, I wrote Octave Mannoni’s famous sentence: I know very well, but nevertheless. I wanted the “but,” slowly shriveling as the balloons deflated, to disappear. Some things, I believe, should simply be without “but.”

And speaking of shriveled words: for some time I find myself thinking about dementia and dissolution. Though dementia is often perceived as an involuntary forgetting, could certain versions of it—physical and mental unraveling—be understood as a desire to dissolve one’s own continuity? My father’s final period with dementia, and the briefly renewed relationships that emerged through that version of it, converged in my mind with the “dissolution” debates within the PKK.

Can we imagine both situations as the breaking apart of the authoritative narrative we know—and the opening of space for new forms of relation?

16 bags, each 70 × 100 cm, 2022–ongoing.

The fragmentation of books and their compression into briquettes is a powerful metaphor. Knowledge becomes unrecognizable yet takes on a physical form. What does this process evoke for you? How do you understand the relationship between fragmentation and reformation?

B.C.: To answer this, I need to discuss False Witness, which is not in the exhibition but briefly mentioned in Yavuz’s text.

False Witness emerged after a guided visit I made in 2001 to a refugee reception center in Ter Apel, the Netherlands. It was first published in 2003, in an edition of 1,000, distributed by Idea Books in Amsterdam. It consisted of 32 photographs and corpus-based data on the English word measure (as in measure, precaution, restriction).

The work acknowledged the insufficiency of witnessing and, rather than attempting centralized documentation, sought to observe—and perhaps transform—the darkness embedded in the asylum and migration policies inscribed into Ter Apel and other institutional architectures.

Through that process, I encountered UNITED for Intercultural Action and their list documenting those who died as a result of Europe’s and its supporters’ racist border policies since 1993, and I began collaborating with them.

About 640 copies of the book have been distributed over the past 20 years. During the same period, asylum and migration policies have caused at least 66,519 documented deaths.

“False Witness is, I think, a log of rage—compressed layers of different testimonies, ready to burn and to scorch.”

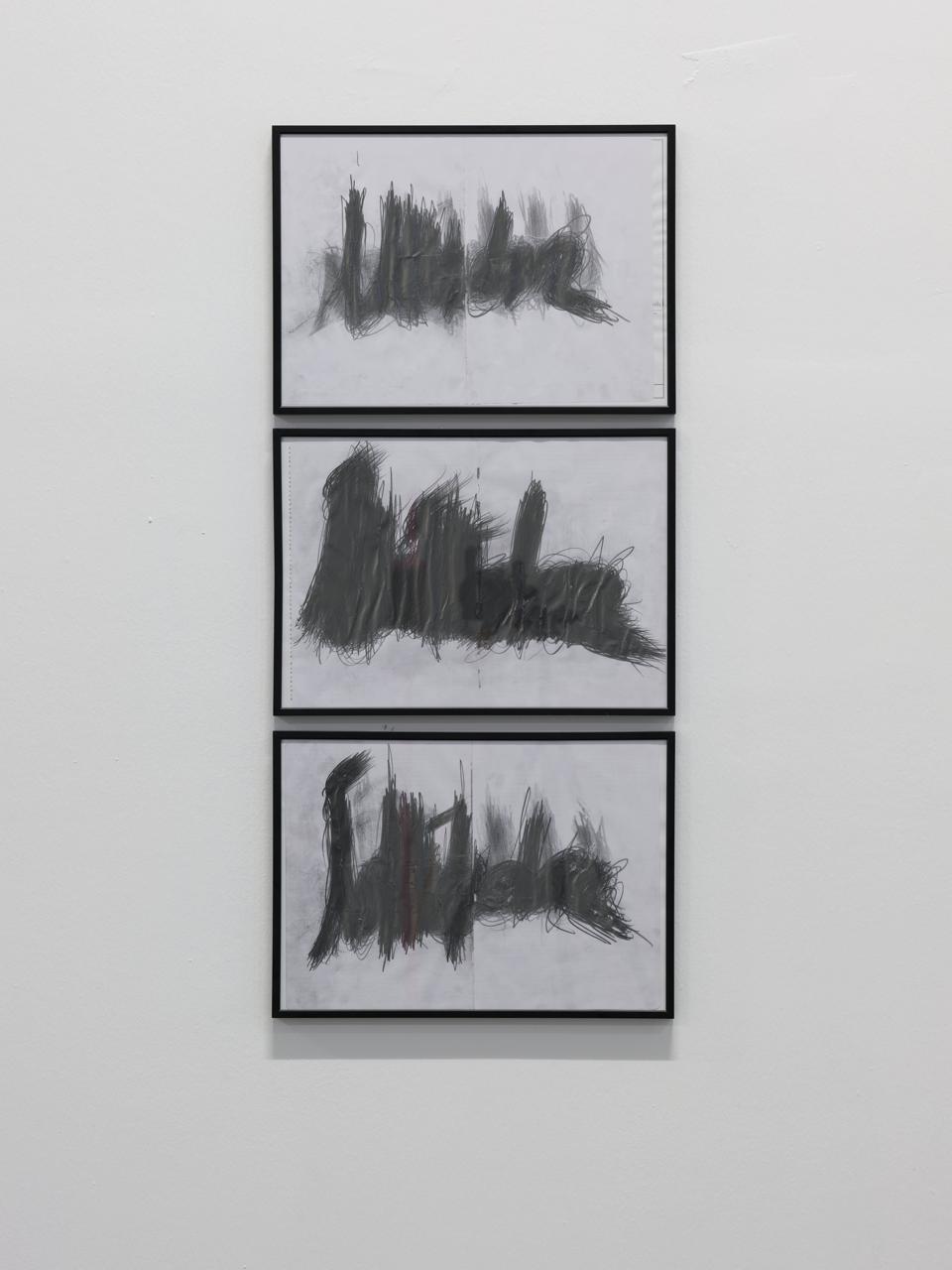

Returning to the work: we soaked each remaining copy in water for two weeks until soft, then tore them apart into pulp—Yavuz, Aslı (Özdoyuran), and I. We pressed each book’s pulp in a briquette machine and left them to dry—each becoming a separate log.

When we began in summer 2023, we planned to show the work in a solo exhibition in Berlin in May 2024. But we canceled the exhibition because the institution maintained silence about the ongoing genocide in Palestine. We continued working—tearing the pages, pressing the pulp.

False Witness is, I think, a log of rage—layers of testimony compressed and ready to burn. And simultaneously, something aware of its insufficiency, not yet ready to give up entirely, and trying—in this new form—to leave space for other possibilities.

44 plates, each 6 × 14 cm, 2021.

When I looked at your work Entschuldigung, I felt ashamed on behalf of those who wrote those apologies. I don’t know if they felt shame writing them, but I felt it for them. This German word Fremdschämen came to mind. I wondered whether apology is possible in the face of what has happened. I also remembered the podcast Impossible Apology you shared with Yavuz. What is the specific weight of an apology for you? What should an apology do?

B.C.: Adalet Atlası is a podcast series by Anadolu Kültür that begins from contemporary rights violations but does not confine justice to legal frameworks.

Impossible Apology is a strikingly lucid episode in which Aylin Vartanyan and Talin Suciyan discuss why apology becomes impossible when the crime is genocide.

“What is needed for an apology to be meaningful? What do the roots of the chosen words reveal? Can genocide be apologized for? What does it mean for a state to apologize without societal support? Can collective apologies create an encounter between perpetrator and victim generations? Did the campaign ‘I Apologize to Armenians’ create such an encounter? Why are perpetrator generations today responsible for the crime of the 1915 Armenian Genocide?”

Here is the link again:

Impossible Apology

The context of Entschuldigung is different. It meets none of Aaron Lazare’s criteria of “what an apology must do.” The parties do not know each other; there is no identifiable wrongdoing. These are apologies produced by the temporary coming-together of parties through Switzerland’s “one percent for art” public building model: police officers whose job is to identify and correct wrongdoing, municipal workers responsible for the art budget, and “independent” curators and artists.

This is how my invitation letter—dated October 7, 2021—began:

“Dear Sir/Madam,

As an artist living in Istanbul, my experiences with law, order, and their modes of implementation have never been smooth. Therefore, it is hard for me to imagine a context in which my contact with any police institution could be frictionless.

When I was invited by curator Adam Szymczyk to participate in an exhibition in the new Zurich City Police Department building in Mühleweg—especially when I first saw the building—the question that came to mind was this: Would collaborating with this institution (artistically) make me an accomplice?”

“Accomplice to whom, to what? Whom would I be turning my back on, and on whose behalf would I be deciding? What would constitute the crime? Who would be guilty, and who would have the right to correct the other?”

“Literary scholar Debarati Sanyal notes that although complicity often refers to involvement in a wrongdoing, etymologically—particularly in French complicité—it also contains meanings of understanding and closeness. She draws from the Latin complicare, meaning ‘to fold together.’ (Banu Karaca, Conversations on Memory and Art, 2020).”

These are apologies with intentionally ambiguous recipients—layers upon layers of entangled parties, like scabbed wounds on a surface corroded by acid.

“An apology should never allow the wrongdoer to feel relief.”

You asked what an apology should do:

Even if the wrongdoer hears they are forgiven, they should not feel relieved. Not in any way. They should apologize without expecting anything—and should not be able to walk away peacefully.

Yavuz Parlar: Honestly, I don’t know what an apology should do because it’s so variable, and I’m not sure what it can truly repair—perhaps nothing. Beyond self-soothing, one must truly feel that the matter concerns the other person. I liked that the Spanish lo siento comes from “to feel”—perhaps for this very reason.

100 × 100 cm, 2025.

When I saw the work Hepsi senin iyiliğin için bitanem (“It’s all for your own good, darling”), I imagined the necklace on a woman’s neck—maybe mine. A heavy necklace made of lead. Lead is heavy, but also dangerous in every sense. You mention the statistical number of deaths caused by lead, but I want to ask about the weight of it for you—its feeling.

Y.P.: Lead is poisonous; it seeps slowly into the body, leaving its mark without you noticing. Wherever there is a dependent relationship—family, romance, friendship—there is weight. As the title suggests: “It’s all for your own good, darling.” A tone that is loving on the surface, protective even, but actually controlling and diminishing. Power can be fueled by good or bad intentions, and this lead necklace becomes its symbol. A trauma that slowly enters us, yet one we continue to carry. It looks like a keepsake, a valuable ornament, but is also a shackle we can’t break—just as you imagined, its full weight resting on the neck.

B.C.: I agree with what Yavuz said, so I’ll keep it brief.

Your role in the exhibition goes beyond the conventional definition of curator. I don’t even want to use the words “collaboration” or “working together.” Can you speak a bit about the process that began with “hello” on May 2?

“We like working together; we somehow get carried away by our shared obsessions.”

Y.P.: We didn’t establish a classical curator-artist relationship. We texted constantly—morning and night—met, talked. Of course, we had functional meetings about the exhibition, but the process unfolded with the intimacy of two people who’ve known each other for years. Banu hadn’t shown her works in Turkey for a long time, and although I’d seen them periodically abroad, I secretly wished to contribute somehow. She imagined a format that would include me from the beginning. I say there was a persuasion process, but it never became a forced imposition; I think we wanted to experience this closeness through friendship. We like working together; we’re drawn along by our shared preoccupations. Even before “hello,” our personal and global states—our eclipses, our conversations—were transforming into this exhibition. We asked ourselves: how do we ground this, what do we turn it into? And what emerged eventually became our pink-covered online journal, nknk-erika.

Your correspondence, which later became the online journal nknk-erika, played what conceptual and practical role in shaping the exhibition? Did this intellectual closeness contribute to your curatorial process, or were there moments where it made it harder to separate yourself from the artist?

Y.P.: I feel that nknk-erika became both the starting and ending point. When building an exhibition, doubts, ideas, budgets, internal and external forces can change everything. Throughout the process, we tossed our experiences and tumult into this bottomless pit. At first we intended to display it physically—“let’s start and see what happens.” Then as days passed and messages accumulated, we imagined it as a digital publication. The single-word replies became genuine correspondence. Making something intimate public is full of anxiety. You ask yourself: “Who cares about our personal lives or our dialogue?” And there’s always self-censorship—but with Banu, I felt it least. The notes I kept on our progress were sent to her through the journal and eventually became the draft of my exhibition text. The exhibition and the journal intertwined, so nknk-erika occupies an important place both inside and outside the show. As you asked, it’s a result of our closeness. I can’t fully evaluate this in curatorial terms, but personally this exhibition opened many things in me. I didn’t struggle to differentiate myself from Banu, though we may have challenged Emre Akyüz, who helped digitize nknk-erika, and Ece Eldek, who designed the exhibition graphics.