The 18th Istanbul Biennial will unfold in three phases, with the first beginning on September 20. The opening chapter spans eight venues, presenting works by more than 40 artists alongside performances and film screenings. In 2026, the Biennial will develop an academy program, and in 2027, the process will culminate with an exhibition and series of workshops.

Drawing inspiration from the idea of a “three-legged cat,” the conceptual framework put forward by Biennial curator Christine Tohmé proposes an unusual form of resistance against destruction and the passage of time. In selecting the participating artists, Tohmé maintained this stance across different geographies and generations. This edition brings together practices from a wide array of countries and backgrounds, while offering unconventional perspectives on displacement, war, and the traces left by time. It asks whether it is possible to see what is often considered a disadvantage in a different light. This Biennial does not stand on solid ground—perhaps fragile, yet resilient.

As part of our coverage, we spoke with participating artists Akram Zaatari, Dilek Winchester, Naomi Rincón-Gallardo, VASKOS, Stéphanie Saadé, and Natasha Tontey about the Biennial’s “Three-Legged Cat” concept and its resonance with Istanbul.

Issue 30 is Now Available!

Get it in both print and digital versions.

Turkish Edition

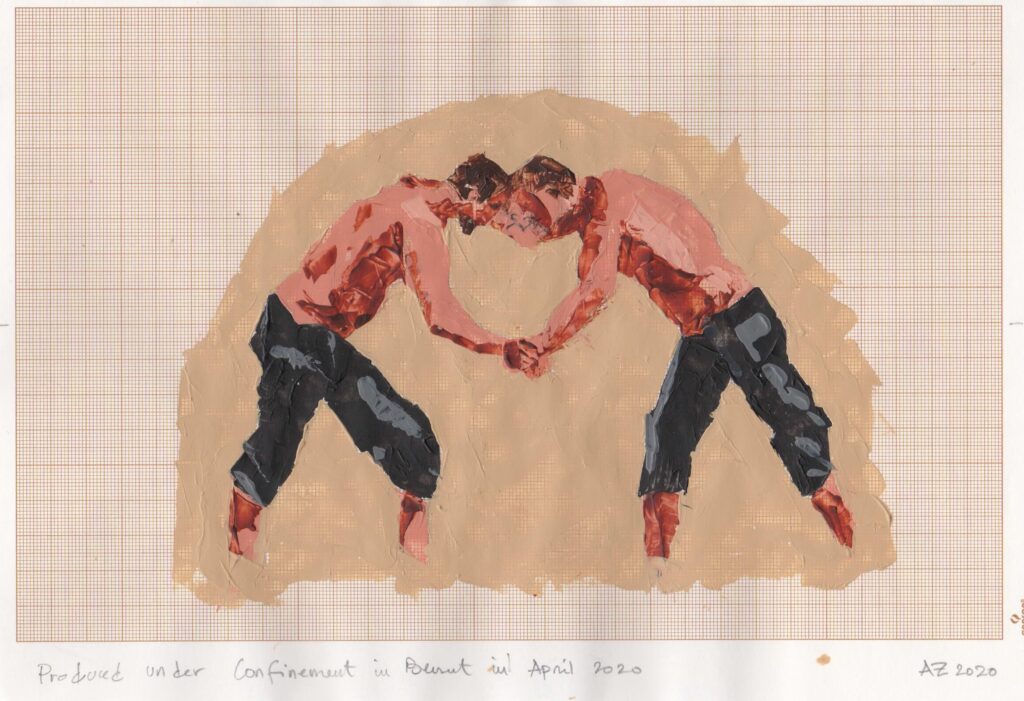

Akram Zaatari

Akram Zaatari has produced more than fifty films and videos, numerous books, and large-scale installations incorporating photographic materials. His work often engages with forgotten histories, the circulation of images during times of war, and the altered temporality of letters lost or delayed. Excavation—both literal and metaphorical—shapes his search for objects, narratives, and missing connections, aiming to reconstruct links severed or eroded over time. A co-founder of the Arab Image Foundation, an artist-run research institute dedicated to the preservation of photography in the Arab world, Zaatari has played a central role in developing discourses on conservation and in shaping Beirut’s critical contemporary art scene. He has participated in international exhibitions such as the 16th Sharjah Biennial (2025), the 55th Venice Biennale (2013), and dOCUMENTA (13) in Kassel (2012). Born in Sidon in 1966, Zaatari lives and works in Beirut.

Your work often draws on Lebanon’s complex history and the current state of the Middle East. How do space and politics come together in your practice?

Space is everything. Society, politics, history, and ecosystems emerge through landscapes, chronicles, and personal narratives, which I see as tools for the future work of an artist, archaeologist, or novelist. My practice treats the landscape and everything within it as an archive of endless secrets, waiting to be excavated and interpreted.

The Middle East is no exception. While it has its own distinctive features, it also shares many dynamics with other regions. Marked by tensions around religion and a colonial past, the Middle East’s relationship with modernity is often complex and contested. These conditions can turn the question of identity into a trap and fuel ongoing conflicts that resist historicization. In this context, art often assumes a more dynamic and inquisitive role than official histories, shaping how individuals remember and make sense of the past.

Istanbul, with its layered history, serves as a scattered archive but also, with the speed of everyday life, as a space of forgetting. In this sense, how did you engage with the city while working within the framework of the Biennial?

Absolutely. Like every city, Istanbul functions as an archive of infinite secrets. Yet cities do not reveal themselves all at once. They require tools to decode them—methods that take into account traces of the past, memories, and other remnants that can be processed and transformed into narratives. In The Museum of Innocence, Orhan Pamuk shows how the archive is always there, changing over time; what is needed is a curious gaze and interpretive interfaces that can turn it into a story, a novel, or an artwork that carries shared experiences, emotions, and values. Every urban settlement holds dense layers of memory that testify to past lives and events, transforming even the most ordinary urban features into a reservoir of remembrance.

I already have a strong connection with Istanbul, having collaborated with the Biennial in 2011 as well as with institutions such as SALT, Boğaziçi University, After Archives, and Gate 27. Over the years, I’ve built meaningful relationships with historians like Edhem Eldem; curators such as Övül Durmuşoğlu, Beral Madra, and my dear friend Vasıf Kortun; and artists like Köken Ergun—we have shared a great deal with one another. For this Biennial, I am presenting sixteen small paintings produced during the COVID lockdown in 2021. Part of the series focuses on the lock positions between wrestlers in traditional Turkish oil wrestling (yağlı güreş), a sport I deeply admire and have even watched in person.

Naomi Rincón-Gallardo

Embracing a decolonial, feminist, and queer perspective, Rincón-Gallardo’s practice of mythological and political world-building draws on Mesoamerican cosmologies, speculative fiction, local festivals and crafts, pop music, and theatrical plays. Her solo exhibitions include Sonnet of Vermin, Hayward Gallery, London (2024); Tzitzimime Trilogy, la Casa Encendida, Madrid (2023); and Artes Mundi 10, Chapter, Cardiff (2023). She has also participated in group exhibitions such as the 59th Venice Biennale (2022) and the 34th São Paulo Biennial (2021). Born in North Carolina in 1979, Rincón-Gallardo currently lives and works between Oaxaca and Mexico City.

The Biennial’s curatorial text speaks of “broken, slowed down, or accelerated” times. Do you think art can reorder time? Is a queer and decolonial temporality possible?

Absolutely. The act of world-building can reorder time and invite others to experience and live it differently. My work is meant to function as an invitation to wander through raw and queer spaces of visual escape. These escapes are designed as playful yet dark dreamscapes, where fragmented and non-linear temporalities resist chrono-normativity and disobey the staged causality of events. Sequences are never fully digested nor resolved into clear conclusions. Instead, time unfolds in overlapping spirals, where the past relates to the present and future in fragmented yet transformative ways.

The understanding that time is not linear can generate narratives that imagine queer and decolonial futures—futures grounded in multiplicity, unpredictability, and the abundance of human and more-than-human subjectivities and perspectives. This vision offers an alternative to the modern/colonial techno-positive mindset that treats life as calculable, extractable, and controllable.

Have you encountered artists, rituals, or cultural elements in Turkey or Istanbul that resonate with your practice?

I am fascinated by İnci Eviner’s allegorical and mythological moving-image worlds, populated with human, non-human, and dream-like characters. Her complex world-building weaves together multiple and simultaneous narratives, scales, histories, and layers of the unconscious, which I find deeply inspiring.

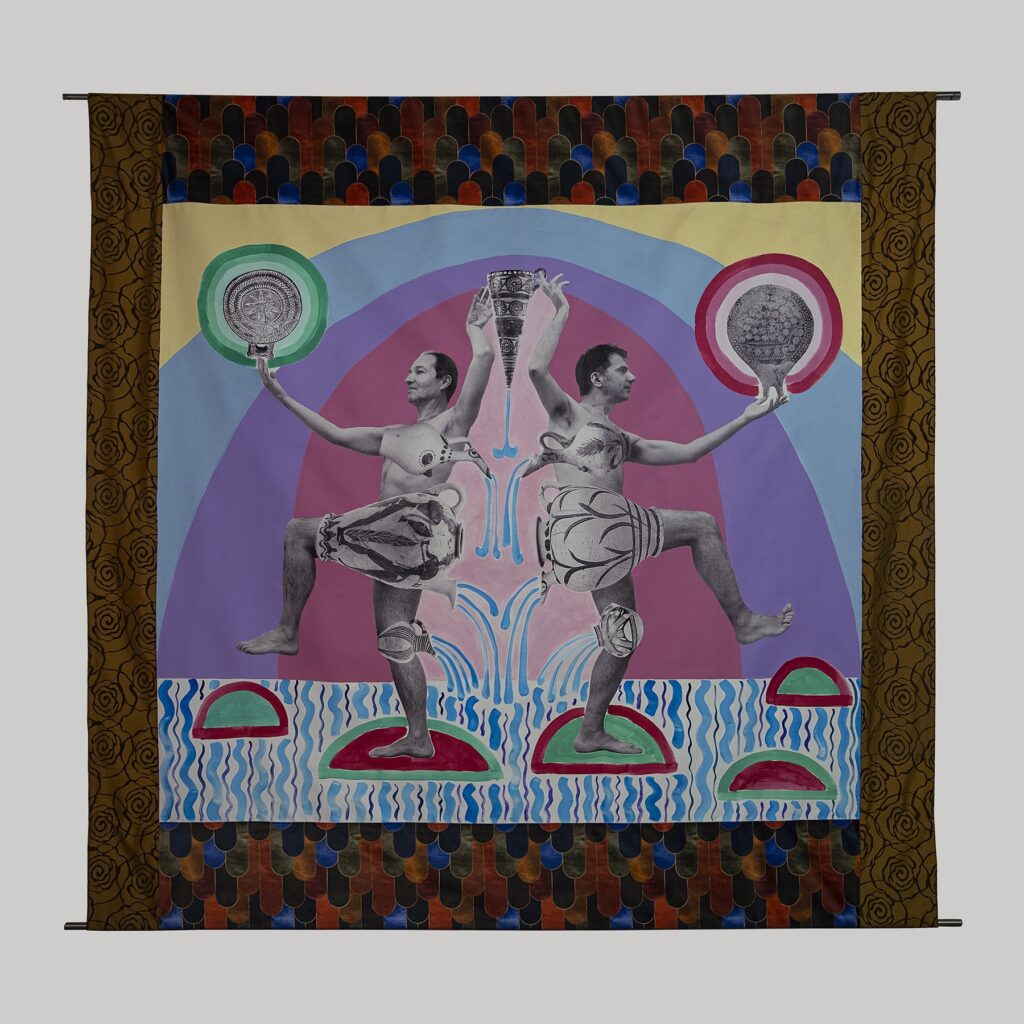

VASKOS

VASKOS is an artist duo formed in 2014 by Vassilis Noulas (b. 1975, New York) and Kostas Tzimoulis (b. 1974, Thessaloniki). Through performance, photography, drawing, installation, publications, and curatorial projects, they explore artistic, sexual, and national identities in hybrid and playful ways. Their work has been presented in solo exhibitions such as Ivory Towers, Asklipiou 99, Athens (2017) and VASKOS, Bangladesh, Athens (2016), as well as group exhibitions including the 9th Thessaloniki Biennale of Contemporary Art (2025), space of togetherness, NEON, Athens (2024), and the Athens Photo Festival, Benaki Museum (2022, 2019). The duo live and work in Athens.

In your work we often encounter unfinished, waiting, or transforming forms. Can an artwork be incomplete? What does incompleteness add to a piece? How would you connect this to the Biennial’s “three-legged cat” metaphor?

The performative element is crucial to our practice. Spontaneity, energies in waiting, emotion, and openness shape the way we approach performance and art. We avoid fixed meanings, rigid hierarchies, and finished forms. Instead, we play with our identities to undo trauma and challenge the violent definitions of race, gender, and class. Intimacy, social bonds, and the sharing of everyday life are the driving forces at the core of our creative process. This openness—this fluidity of self and identity—transforms into forms of resistance and resilience. We are constantly changing, mutating, and through change, we mislead the “enemy.” Playful and “unfinished” works are survival strategies. An incomplete work resists fixed meanings and control, encouraging the viewer’s imagination and participation in the ongoing process. We identify with the three-legged cat; its resilience reflects our artistic and social strength in these dark times.

Your works often use everyday materials filled with cultural references. While producing your work for the Istanbul Biennial, did you notice any similarities between Istanbul and Athens in this regard? If so, how did they shape the work you presented here?

Exhibiting our work Forever Shedding at the Istanbul Biennial, we observed similarities between Istanbul and Athens—particularly in how their historic centers are undergoing radical transformations due to mass tourism, real-estate speculation, rising costs, and neoliberal policies. These processes create tensions and conflicts between the old and the new, shaping collective identities and uncertainties.

In our work, pitchers serve as ambiguous symbols—expressing both the grandeur of ancient vases and the everyday joy of shared heritage. By queering these forms, we critique the reduction of tradition into a touristic spectacle and the exoticization of our identities under the gaze of visitors. As VASKOS, our method is consciously collaborative, distancing itself from individual authorship. Our processes echo traditional folk practices in which creativity is embedded in social and everyday life. Through hybrid materials, we reclaim cultural memory as fluid, collective, and open to reinvention, reflecting the layered, improvisational realities of local communities.

Dilek Winchester

Through her meticulous research, Dilek Winchester explores how printed words shape a sense of belonging. Her interest in communities formed through publishing extends from artist books to the hybrid print culture of the 19th-century Ottoman Empire. Her areas of research include Turkey’s alphabet reform, the symbolic meanings of alphabets, and the politics of translation. Her solo exhibitions include Void and Base, Depo, Istanbul (2019) and A Solo Show, EMST – National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens (2012). Her works have previously been shown in the 16th Sharjah Biennial (2025); Translating into Socialism, Salt Galata, Istanbul (2024); GLOSSOLALALA, Arter, Istanbul (2024); and Self-Determination: A Global Perspective, IMMA, Dublin (2023). Born in Istanbul in 1974, Winchester continues to live and work in her native city.

Your works often carry a visual silence and typographic simplicity. How do they resonate with the biennial’s themes of “rest,” “pause,” or “withdrawal”?

Two of my works are being presented at the biennial. The first is a new video titled 410 Letters: On Reading and Writing (Albanian). The video incorporates 12 different alphabets once used in the writing of Albanian. At its core are cacophonic murmurs composed from the sounds of these letters. The sound design was created by Ahmetcan Gökçeer and the cinematography by Ece Latifaoğlu. The work opens up a visual and sonic interval, a playful pause within forgotten pages of history. The symbolic charges of familiar alphabets, or the traces of invented ones that never came into full use, are traced here. Letters from obsolete alphabets appear alongside those of the contemporary one—without hierarchy, in accidental juxtapositions. Inevitably, one expects the sounds to coalesce into words. Perhaps this is about suspending that expectation, creating a space without words, without speech.

My second work is a new iteration of an earlier text-based piece. It brings together different alphabets once used to write Turkish in the 19th century into a hybrid text. When read aloud, the text is in Turkish, yet it feels as though it has turned its back on us today. The work reflects on the role of alphabets and print in creating belonging and communities.

How does the “language” or “voice” of Istanbul—shaped by spaces of political and cultural conflict and encounter—inform your practice?

Many of my works address the languages and alphabets of Istanbul, so the connection is both direct and obvious. Rare books printed in Istanbul, inscriptions on building façades that left their mark on the city’s public spaces, and the cultural productions they signify all surface in my work. In this sense, my artistic production is deeply rooted in the city, yet also extends across a wider geography shaped by Istanbul’s historical ties and layered diversity. What interests me are these intertwined traces and narratives. As a result, my work is not insular but permeable, establishing connections in multiple directions. These resilient qualities are at the very heart of what I do—and they are also embedded in the very fabric of Istanbul.

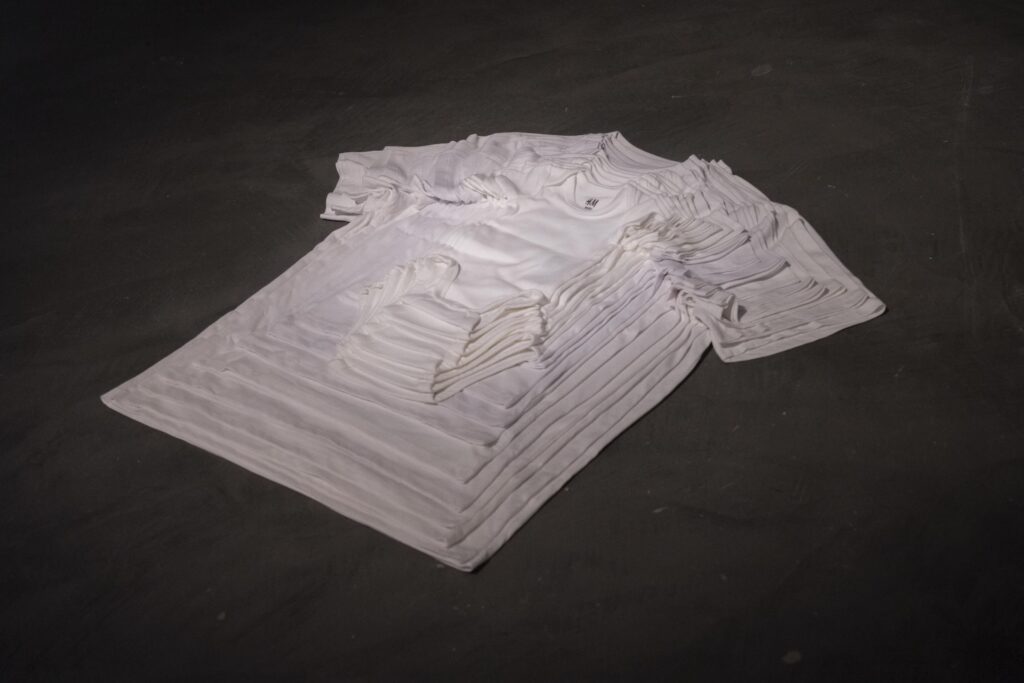

Stéphanie Saadé

Stéphanie Saadé’s artistic practice develops a language of allusion, playing with poetic and metaphorical elements. By offering viewers clues and signs—sometimes even passages without images or sound—she invites them to decipher these fragments as part of a larger narrative. Her solo exhibitions include The Encounter of the First and Last Particles of Dust, Sursock Museum, Beirut (2025); Building a Home with Time, Kunsthaus Pasquart, Biel (2023); and The Travels of Here and Now, Museum van Loon, Amsterdam (2022). Group exhibitions include Présence, Centre Pompidou, Paris (2023); Luogo e Segni, Punta della Dogana, Venice (2019); and the 13th Sharjah Biennial (2016).

Born in Beirut in 1983, Saadé lives and works between Paris and Beirut.

What does it mean for you to create or present work in a multilayered city like Istanbul? How do you read the city as a “surface” or a “space of memory”?

Speaking of layers immediately brings to mind the works I will present in Istanbul at the 18th Biennial curated by Christine Tohmé, since these works are themselves structurally layered. Pyramid consists of five textile sculptures made of stacked layers of standard garments for each body. The clothes are new, which makes them immediately relatable and allows visitors to project themselves onto the pyramids, recalling their former (younger) or future (older) selves—thereby activating memory and imagination. Through their forms and processes, the works function as a kind of inverted archaeology, with the smallest or oldest layer at the top. They evoke organic formations such as tree bark or stalagmites that embody growth and time, yet again in a reversed understanding.

My imagined relationship with Istanbul recalls Proust’s bond with Venice: he longed to visit but was always prevented from doing so. I look forward to placing these contemporary archaeologies within the city’s ground and bringing them into dialogue with the city and its inhabitants.

In an age of accelerating destruction, displacement, and uncertainty, what kind of political meaning do you see in your art’s proposal of “pausing” or of “another form of remembering”? Could you explain its connection with the Biennial’s “three-legged cat”?

My works are nourished by everyday experiences, and the Pyramids I present at the Biennial are inspired by my experience of motherhood: you witness a child’s growth through the clothes they quickly outgrow. Between these stages, by layering old and new garments, you can physically measure the centimeters gained or yet to be gained. We are going through an extremely difficult period, and the works we produce as artists—whether they directly respond to the times or not—are inevitably conceived within this historical and political context, inseparable from it.

Pyramid, made of universal garments wearable from birth to death, is mostly displayed horizontally on the ground. Together they reconstruct the shape of a body, but they can also suggest a body dispersed in space. In this sense, the work resonates with the powerful idea of the three-legged cat: for me, it represents both a transformed existence and one that carries on, walking forward and sustaining itself with hope, even under unbearable conditions.

Natasha Tontey

Natasha Tontey’s artistic practice explores fictional narratives surrounding the histories and myths of “manufactured fear.” Her works imagine the possibility of alternative futures—not from the perspective of established institutions, but through the personal struggles of marginalized and excluded individuals. Solo exhibitions include Primate Visions: Macaque Macabre, Museum MACAN, Jakarta (2024), and Garden Amidst the Flame, Auto Italia, London (2022). Group exhibitions and screenings include the 36th FID Marseille (2025); KANAL–Centre Pompidou, Brussels (2023); Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin (2021); and transmediale, Berlin (2021).

The Istanbul Biennial proposes the metaphor of the “three-legged cat.” What does this figure evoke for you, and how do you connect with it in your work?

The “three-legged cat” resonates with me as an imagined figure embodying both fragility and perseverance. In Garden Amidst the Flame, I draw from Minahasan cosmologies to reimagine survival not through power or dominance, but through vulnerability, adaptability, and care. The work critiques hyper-masculinity by proposing alternative forms of resilience rooted in myth, kinship, and interdependence. Like the three-legged cat, which finds new ways of moving despite its limitations, the film emphasizes that resilience stems not from perfection but from the ability to invent different modes of existence within damaged conditions.

Within Istanbul’s layered fabric, have you had the chance to explore the histories and myths of the city or of Turkey?

Although I have never visited Istanbul, its layered myths align with my interest in how stories endure through generations by continually transforming. Garden Amidst the Flame approaches myth as a living, ever-evolving force that challenges dominant narratives of heroism and masculine conquest. In this sense, the work finds kinship with Istanbul itself: a city of multiple histories, fragments, and transformations, a place that—like the three-legged cat—survives through constant reinvention as an unfinished body.