Beauty has never been a fixed concept. Across time and culture, it has meant fertility, virtue, eroticism, power, purity, and even submission. Far from being a universal truth, beauty standarts changed over time according to each generation’s beliefs, fears, fantasies, and technologies. Nowhere is this more visible than in the visual arts. For thousands of years, artists have portrayed the human body and they especially worked on the female form. These artworks are not just the result of the artists aesthetic admiration, but also as a reflection of society’s point of view on religious authority, gender politics, class divisions, colonial desire, and the ever-changing role of women in public and private life.

Beauty standards have constantly shifted rapidly yet one thing has remained unchanged: the persistent effort to shape, control, and assign roles to women through external ideals. When we recognize this pattern, it becomes necessary to reevaluate our perspective. Is it truly reasonable to live according to rigid beauty norms and accept a reality where women are confined by them? Or should we embrace ourselves as we are and begin to live lives that extend beyond the appearance of the bodies we inhabit? Recognizing this cycle and seeing how different each time periods expectations is the first step toward reclaiming autonomy over our bodies and narratives. To explore this, we can examine how beauty standards have been shaped throughout history by analyzing artworks from the most recent period to the most distant past.

From the figures of the prehistoric Venus sculptures to the divine symmetry of classical antiquity, from the veiled Madonnas of Byzantine mosaics to the nudes of Rococo fantasy, each portrays their times expectations onto the female body. Over time, ideals have narrowed and expanded, shifted from plump to thin, from natural to artificial, from static symbolism to living, breathing realism. In the 21st century, these tensions have reached their peak. Beauty is now curated through social media. We are all familiar with today’s beauty standards and in a world where these unrealistic norms are widely normalized, the presence of artists like Jenny Saville, who challenge the dominant gaze, offering raw, confrontational depictions of the body that resist idealization offers hope that change is possible.

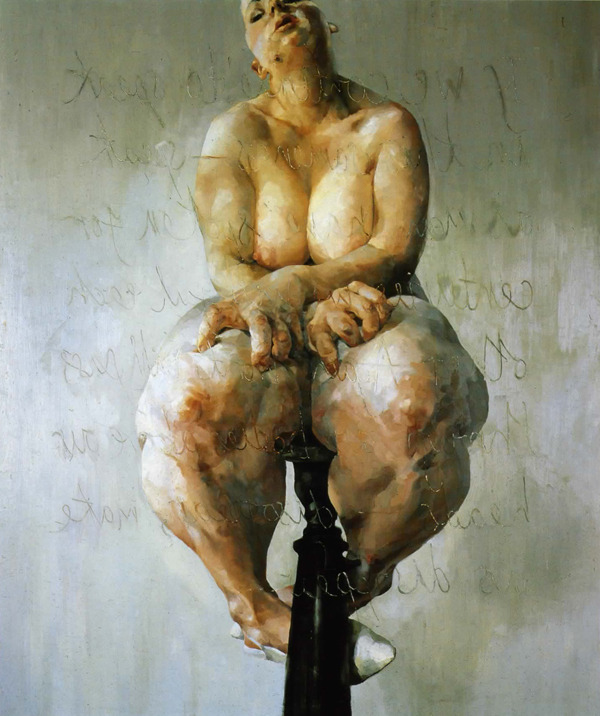

Jenny Saville and the Rebellion Against Unreal Ideals (1990s–Present)

British painter Jenny Saville stands out as one of the few contemporary artists who challenge modern beauty ideals with such force. Rejecting the polished, filter-filled aesthetic of Instagram and the perfection just pursued through cosmetic surgery, her large-scale oil paintings embrace the raw, untouched truth of the human form. She paints women, often herself with realistic details like bulging folds of flesh, bruises, surgical marks, and all. In her breakthrough work “Propped” (1992), a massive nude self-portrait, Saville depicts her own body not as a passive object but as a fleshy presence. The figure’s dimpled thighs and full torso dominate the canvas, confronting the viewer with the sheer physicality of female flesh. Saville explicitly challenges traditional ideals of beauty, and changes the centuries of male-dominated art. Jenny Saville’s paintings don’t just ask us to admire how a body looks from the outside. Instead, they show us what it’s like to live inside a body. In some of her works, she even includes quotes from feminist thinkers, for example, in “Propped,” a quote by philosopher Luce Irigaray is scratched onto the surface. Her art makes it clear that women haven’t “failed” to match beauty standards because of their bodies, but because those standards were never made by or for them in the first place.

Contemporary Contrasts – From Heroin Chic to Instagram Glam (1960s–Today)

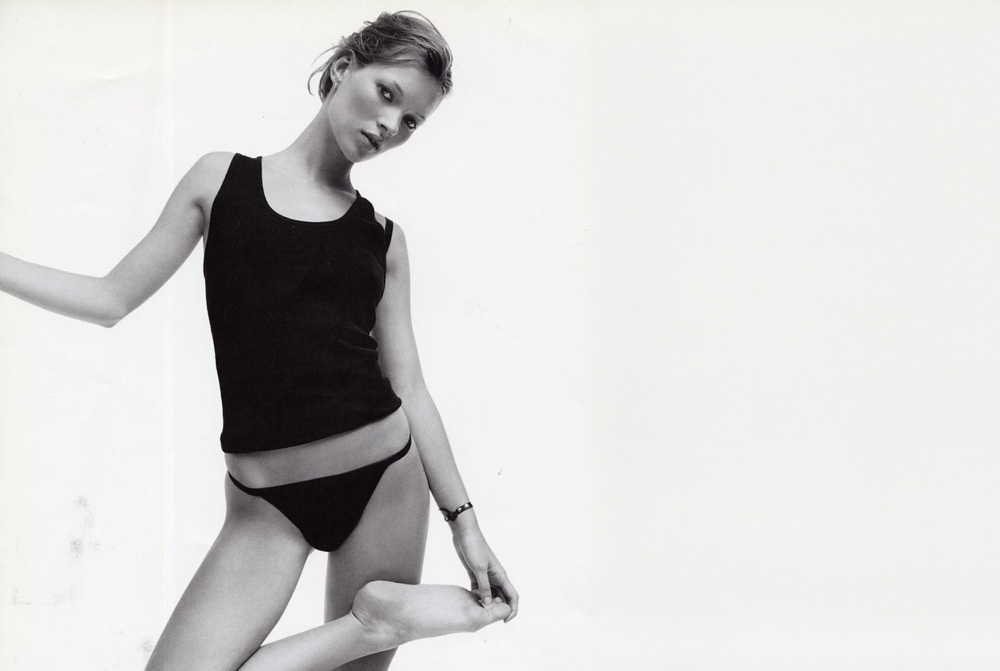

In the past half-century, beauty standards have continued to change in a high speed and they often reflect social movements, technology, and media influences. The 1960s ushered in an era of ultra-slim chic. British model Twiggy, with her stick-thin frame, boyish crop, and doe-eyed gaze, became the face of a youthquake revolution in fashion. Her look popularized what one critic called the “aesthetics of hunger” and suddenly thin was in and slowly everyone is against the curvy, conservative 50s ideal. By the 1990s, this trend took a darker turn with “heroin chic,” which got more popular after supermodel Kate Moss. Pale skin, gaunt features, and a languid, world-weary attitude were glamorized. However, the late 20th century also saw growing pushback against singular beauty ideals. As we entered the 2000s and 2010s, media and celebrity culture birthed a new ideal and its the so-called “Instagram face.” Full lips, high cheekbones, sculpted nose, flawless airbrushed skin, and an exaggerated hourglass figure dominates social media feeds. Accelerated by filters and photo-editing apps, these digitally perfected images have “subtly shifted the goalposts” of beauty, making the extreme now seem attainable and normal. Studies show that the more time people spend scrolling past these endless images of perfectly sculpted faces and bodies, the more likely they are to feel dissatisfied and even consider altering their own appearance to match.

After seeing the highest demand in cosmetic procedures, contemporary art and advertising started to celebrate diversity and subvert old norms : we see models of all sizes, ages, and ethnicities gaining visibility, and terms like “beauty ideal” being questioned as never before. Beauty now become a site of protest. It’s a battleground between the industry selling narrow perfection and a growing movement embracing authenticity and variety. Jenny Seville is one of challenger artists of this era and she is not alone at portraying raw reclamation of the female form because other contemporary artists and movements.

Modernism – Flappers to Hourglass (1900s–1950s)

The 20th century brought rapid, drastic shifts in beauty ideals, reflected in art and popular culture alike. After 1900, as women’s social roles began to change, so did the preferred image of their bodies. The 1920s saw the rise of the flapper who’s a young women who defied Victorian norms by embracing a boyish, androgynous style. In art deco paintings and early fashion photography, the ideal flapper had a petite, straight figure with minimal curves, short “bobbed” hair, often confident and playful. This look ,which is portrayed by icons like Louise Brooks, projected modernity and liberation, with feminine curves deliberately underestimated. For perhaps the first time, a slim, adolescent physique was in vogue, breaking the standards of prefering fuller forms.

In post-WWII art and media, the hourglass figure reigned once more. Starlets like Marilyn Monroe re-popularized a cinched waist and pronounced bust and hips as the feminine ideal. The 1950s “bombshell” image with domestic fertility and sexual allure messages became a cultural archetype, celebrated both on canvas and in advertising. Women’s bodies were alternately stylized as fashionable objects or sites of domestic promise, but always the pressure remained to conform to the trending shape of the decade.

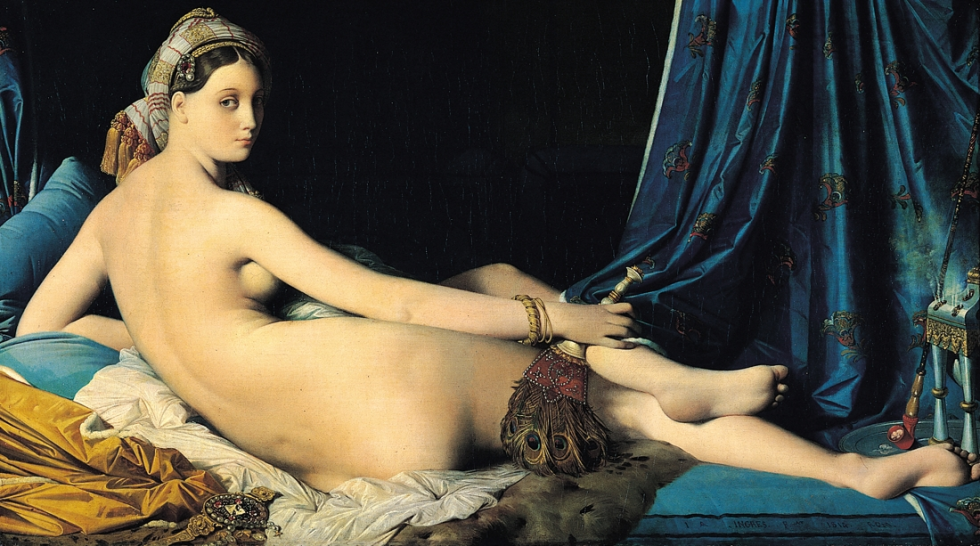

“Exotic” Fantasies and 19th-Century Ideals

The 18th and 19th centuries also saw the rise of the European male gaze projecting its fantasies onto Eastern women art; Orientalism . Painters like Ingres and Delacroix portrayed Middle Eastern and North African women as odalisques in harems, available for Westerns. In these works like Ingres’ Grand Odalisque or Gérôme’s Women of the Harem, the “Oriental” beauty is sensual and passive. Women typically has long dark hair, large almond eyes, an hourglass figure with a narrow, cinched waist and generous hips and often shown nude or semi-nude, yet adorned with veils or jewelry to lend an “exotic” flavor. Crucially, she is depicted as existing purely to be looked at like a decorative object in a male fantasy, reflecting colonial attitudes of the time.

Back in Europe, the Romantic era (c. 1800–1850) crafted a different ideal: the beautiful woman as a delicate, soulful muse. Romantic artists and poets idolized women who were sensitive, melancholic, and even tragic. In the past, the ideal woman was often seen as weak, pale, and emotional. Paintings showed women with dreamy looks, surrounded by mist and moonlight. At the same time, Romantic artists gave women symbolic roles, like Liberty, Victory, or Truth. In Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1830), for example, a woman represents Liberty at the front of the scene. Her dress is falling, showing a strong body that looks both motherly and sensual, full of revolutionary energy. She appears powerful, but still not fully real — she is idealized. By the late 19th century, during the strict Victorian era and the rise of Neoclassicism, beauty ideals became even more narrow and controlled.The “proper” woman is now has to have impossibly cinched waist, delicate hands and feet, and a porcelain complexion signalling class purity. Corsets and crinolines sculpted bodies into fashionable silhouettes, the hourglass taken to an extreme, while cosmetics and elaborate coiffures completed the image of gentle femininity. Across the movements of the 19th-century , a woman’s “beauty” was rarely just personal but it was more political and symbolic while portraying the era’s colonial desires, nationalist fervor, or moral codes.

Baroque and Rococo – From Rubenesque to Refined (17th–18th centuries)

Artistic taste changed dramatically over the 1600s and 1700s. In the Baroque period wealth was beauty. The preferred female form was voluptuous, full-figured, and ripe, reflecting Baroque art’s love of drama and grandeur. Peter Paul Rubens’ famous Three Graces(1630s) which is an artwork of three nude women with ample hips, round bellies, and glowing flesh shows the ideal. Such “Rubenesque” women represented fertility, wealth, and erotic allure. Painters often describes these women as mythological figures or goddesses, using allegory as a pretext to celebrate the naked female form in all its curvy glory.

By the mid-18th century, however, the Rococo style introduced a more playful, delicate vision of femininity. Beauty ideals became more coquettish and youthfully dainty. Artists like François Boucher painted rosy-cheeked shepherdesses and nymphs with slimmer waists and an air of lightness. Tight waists, soft oval faces, and an almost porcelain doll-like fragility is now considered ideal. In porcelain figurines of the era, ladies have waspish waists and elegantly posed hands. Wealthy patrons often commissioned portraits of women showing them as mythological figures like Minerva or Diana. Thus, across the 17th and 18th centuries, the pendulum swung from robust opulence to a flirtatious refinement, but in both cases female beauty was tied to luxury and fantasy. Women were depicted as either goddesses of wealth or charming naives in a pastel pastoral scene, all existing for the pleasure of the viewer.

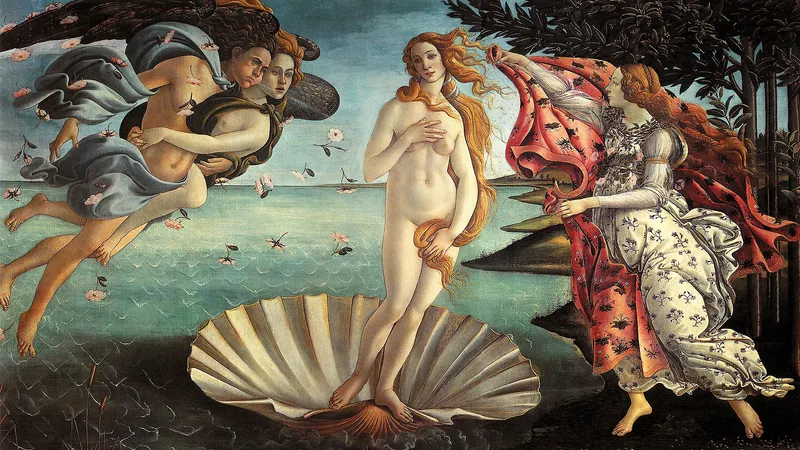

Renaissance Revival of the Classical (14th–16th centuries)

The Renaissance brought a rebirth of classical ideals and with it, a more celebratory view of the human body. Artists returned to studying proportion, symmetry, and anatomy, infusing mathematical order into depictions of female beauty. The result was a blend of the divine and the earthly: women in Renaissance art were painted as at once goddess-like and sensuously real. In Sandro Botticelli’s Birth of Venus(c.1485), for example, the nude Venus stands in contrapposto, her form at once idealized with smooth skinned, long-limbed, yet alluringly human in its soft curves. Writers of the period described the standards that a woman’s beauty should follow classical principles, a harmonious balance of features, complemented by fair skin and a demure posture of grace. Notably, being beautiful did not mean being thin: Renaissance beauty prized a full figure with flowing curves. The ideal woman is described having golden hair, a high forehead, dark eyes, rosy cheeks, fleshy arms and a rounded body which are the signs of health and fertility. Indeed, thinness was considered undesirable, even a sign of illness. Beauty became something to strive for and was increasingly seen as a woman’s duty to uphold in society.

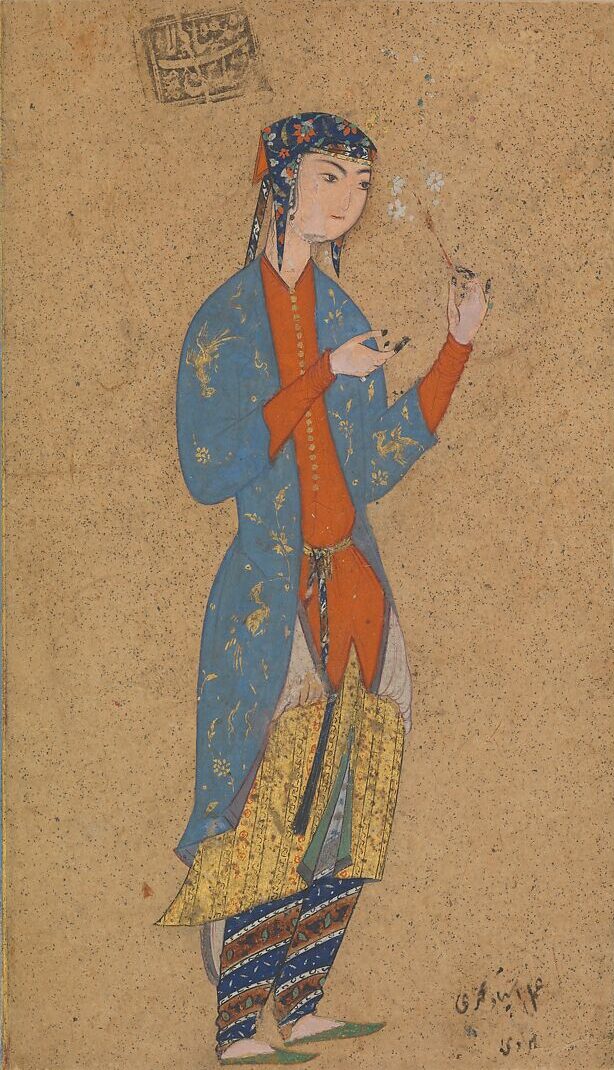

Poetic Grace in Islamic and Asian Art (8th–17th centuries)

Beyond Europe, beauty standards took on different nuances. In the Islamic world, where figurative art was often limited, female beauty was celebrated in poetry and refined courtly miniatures rather than monumental nudes. Persian miniatures depicted women in an idealized, poetic fashion: almond-shaped eyes, a small delicate mouth, long dark hair, and a fair complexion comprised the canonical look. These refined features, often seen in illustrations of heroines like Layla or Zuleika, were less about raw sensuality and more about an otherworldly elegance.

Meanwhile in East Asia, standards evolved across dynasties. In China’s Tang Dynasty (7th–10th century), plump figures and round faces signified prosperity and health. Tang court paintings by artists like Zhou Fang show full-figured palace ladies with composed, serene expressions, embodying fertility. By contrast, in Heian-era Japan (794–1185), aristocratic women pursued an ethereal look: they grew their hair exceedingly long, powdered their faces ghost-white, and painted tiny red lips, giving them an almost doll-like delicacy. A touch of melancholy (yūgen) in expression was admired as a mark of depth. Across these cultures, beauty was closely tied to cultural values showing that ideals of attractiveness are never universal, but always culturally coded.

Ideal of Purity in Medieval Europe (11th–14th centuries)

In the Middle Ages, especially in Gothic Europe, beauty ideals were tied to religious morality and social hierarchy. Women’s attractiveness was equated with signs of virtue, humility, and noble birth. Pale, almost translucent skin symbolized purity (often achieved by avoiding the sun or even using toxic white lead makeup), and a high forehead was so desirable that women plucked their hairlines to achieve it. We see this in Gothic paintings where the Virgin Mary or aristocratic ladies have elongated, dome-like foreheads and demure expressions. In art, female figures fell into a virgin Mary–whore dichotomy: they were depicted either as saintly, modestly dressed, eyes downcast or as the dangerously seductive Eve or temptress. In either case, individuality gave way to archetype. Gothic sculptures and altar paintings present women as slender and long-limbed under flowing garments. Beauty was a moral concept: it lay in virtue and devoutness, with physical traits serving as external indicators of an inner spiritual state.

Spiritual Beauty in Byzantine Art (4th–10th centuries)

With the rise of Christianity, art shifted away from celebrating the body towards nurturing the soul. Physical allure was de-emphasized as spiritual purity became the ultimate ideal. In Byzantine mosaics and icons, the holy woman, exemplified by the Virgin Mary, is depicted as modest, static, and otherworldly. For instance, the 9th-century Theotokos mosaic in Hagia Sophia shows Mary robed and haloed while holding the Christ child, her features stylized into an impersonal grace. The female body was veiled and abstracted, with no hint of the nude flesh common in pagan antiquity. Beauty was thus defined as chastity, piety, and ethereality, in line with Christian ideals. The body was to be a “temple,” often literally gilded or halo-crowned in art, not an object of human gaze.

Antiquity – Symmetry and Ideal Forms (c. 3000 BCE–400 CE)

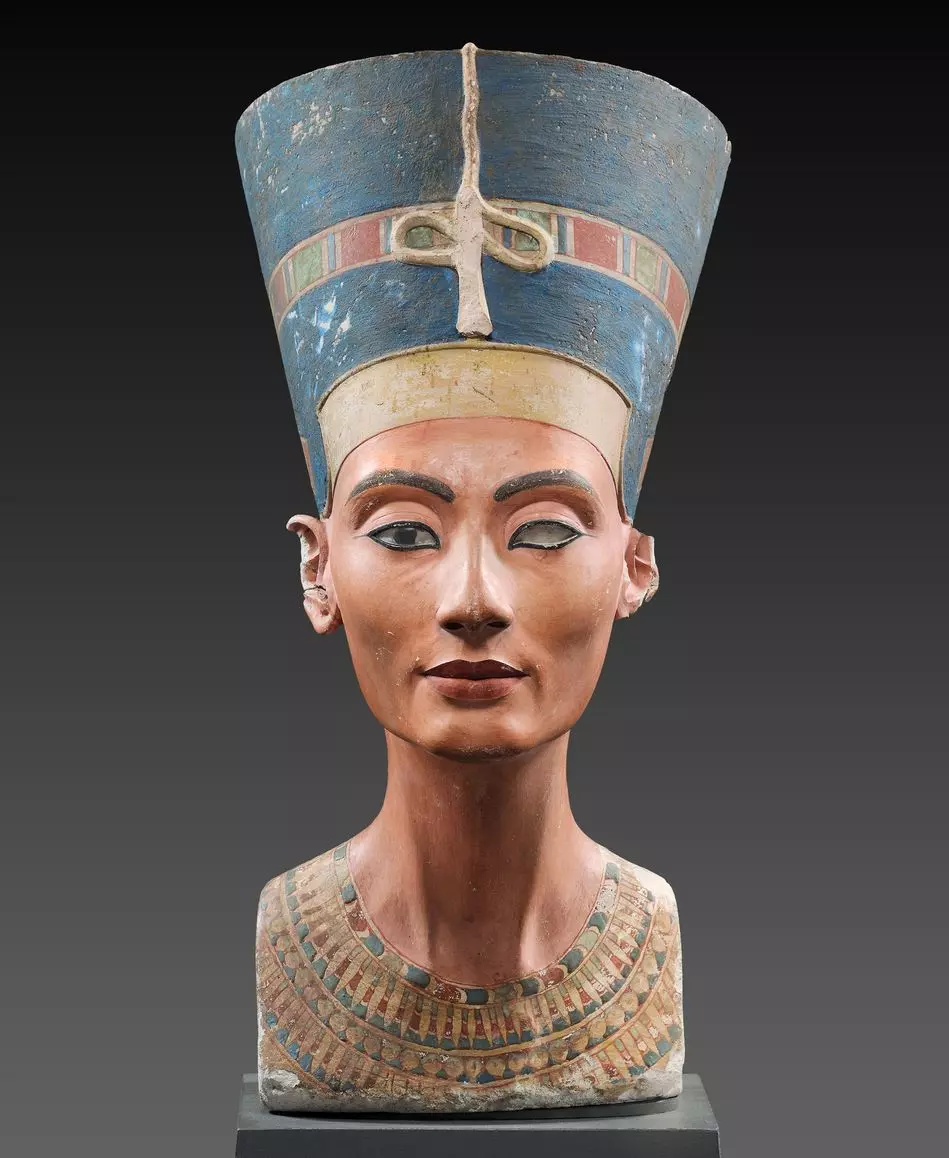

In the ancient world, concepts of beauty became intertwined with harmony and divine order. In Egypt, elegance and symmetry reigned: a beautiful face was thought to have fine, regular features, large kohl-lined eyes, a long graceful neck, and a slender, youthful figure, serene expression, refined nose, and high cheekbones.

Meanwhile, the Greeks exalted mathematical proportions and the “golden ratio” as the template for beauty. Sculptures like Praxiteles’ Aphrodite of Knidos and the later Venus de Milo (2nd century BCE) presented woman as goddess with symmetrically featured, smooth-skinned self. These statues’ soft, rounded forms emphasized the power of feminine sexuality and fertility within a balanced form. Beauty in this era meant an idealized nude meant to be admired. This era physical perfection believed to reflect divine harmony.

Prehistoric Fertility over Aesthetics (c. 30,000–3000 BCE)

The earliest artworks suggest that prehistoric societies celebrated fertility and life-giving power rather than “beauty” in a modern sense. The famed Venus of Willendorf(c.24,000 BCE), a small Paleolithic statuette with exaggerated hips, breasts, and abdomen, exemplifies how fertility and motherhood were idealized. These figurines lack facial detail and individualized features, indicating they were likely ritual objects or fertility totems, not portraits of physical attractiveness. In this era, a healthy body symbolized survival and prosperity in harsh environments.

(Image credit: Anadolu / Getty Images).

From ancient times to today’s Instagram era, it’s clear that every period shows and shapes what people think is beautiful. Today, technology and beauty products create new questions about what’s real and how we see ourselves. Artists like Jenny Saville remind us that we should always question beauty, because when we look closely at it, we learn not just what we like, but also what we believe about being human. Jenny Saville presents The Anatomy of Painting at the National Portrait Gallery in London. The exhibition showcases 45–50 works, including her breakthrough piece Propped, and redefines “anatomy” beyond the body but layering it with tempo, texture, and emotional force. Don’t miss the chance to experience this journey through the human form.