The Kiefer/Van Gogh exhibition, which opened at the Royal Academy in London, brings together Anselm Kiefer’s dark historical vision with Vincent van Gogh’s bright dreams. The result is a confrontation that is as shocking as it is rare in art history.

Vincent van Gogh was born in 1853, during a relatively peaceful era. In 1890, at the age of 37, he took his own life in a wheat field. But what if he had lived? In his 60s, he would have witnessed World War I, and by his 90s, Nazi Germany and the horrors of Auschwitz. Anselm Kiefer’s 80th birthday exhibition at the Royal Academy explores precisely this fantasy: how would Van Gogh have painted if he had witnessed the horrors of the modern world?

Kiefer’s interest in Van Gogh is not new. At the age of 18, he received a travel grant to follow in Van Gogh’s footsteps; he traced the artist’s footsteps along a route from Holland to Arles. Since then, Van Gogh’s inner turmoil and passionate connection to nature have resonated in Kiefer’s large-scale canvases and sculptures woven with historical references.

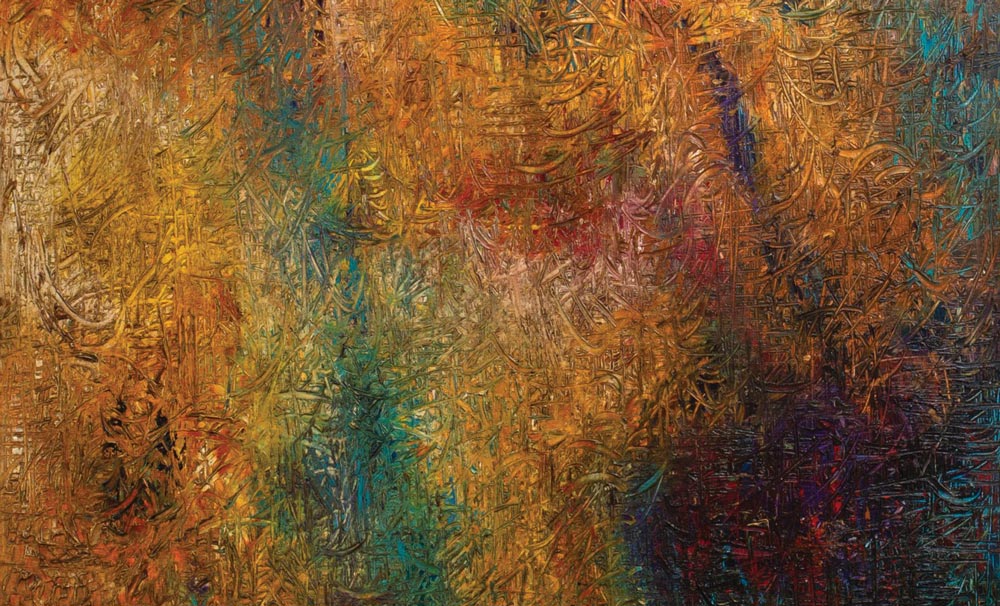

The exhibition features a wide selection of works, ranging from Kiefer’s early drawings to his current works, which are a direct response to Van Gogh. Among these are enormous canvases such as The Last Load (2019), measuring 7.5 meters. The winding tracks under a black sky, reminiscent of a wheat field, evoke the rails leading to Auschwitz, while straw stalks embedded in thick layers of paint scream out the silence of the past.

In Kiefer’s dark universe, some of Van Gogh’s paintings take on eerie connotations. Shoes, dated 1886, is no longer just a lament for an artist’s life, but for lives that have been destroyed. Piles of French Novels are like gravestones, evoking forgotten stories piled one on top of the other.

One of the most striking pairings is Van Gogh’s 1890 painting Wheatfield with Crows and Kiefer’s reinterpretation titled “Nevermore.” The black crows in the wheat field that Van Gogh drew before his death reach enormous proportions on Kiefer’s canvas. As flocks of crows attack us from the sky, Paul Celan’s “death fugue” verses echo: “We dig a grave in the sky—there is plenty of room.”

Where Hope Ends, Memory Begins

This exhibition establishes not only a romantic but also a traumatic connection with Van Gogh’s art. Kiefer’s dark perspective on Van Gogh elevates the exhibition to a different level. However, whenever Kiefer attempts to capture Van Gogh’s hopeful and luminous side—particularly with his sunflowers covered in gold leaf—he falls short of being convincing. His relationship with nature is no longer innocent, because “no one can look at nature with the same fresh joy as Van Gogh did.”

This encounter at the Royal Academy reveals Kiefer’s personal and historical admiration for Van Gogh with deep insight, while leaving us with the question: Can art truly carry historical horrors?