Ten years ago, we lost Yaşar Kemal—a magician who deciphered the language of the earth, a lover who listened to the song of water, the guardian of the “Garden of a Thousand and One Flowers.” Today, the best way to honor his legacy is to stand against injustice and show respect for humanity, nature, and life itself. On the 10th anniversary of his passing, we remember Yaşar Kemal with great longing.

Yaşar Kemal was more than a writer; he was a voice that echoed from the Taurus Mountains to the world, a storyteller who endured the scorching sun of Çukurova, and a pen of resistance against injustice. On February 28, ten years ago, at the end of winter, he left us at the age of 92. That day, Turkey did not just lose a writer; it lost a sage who deeply understood the stories of the land, water, and people. A decade has passed, but his absence is felt more profoundly with each passing day. Because he was not just a literary figure—he was the conscience of the people.

Behçet Necatigil’s Dictionary of Names in Our Literature refers to him as a child of 1922, while Tuba Çandar’s Yaşar Kemal: A Photobiography states he took his first breath in January 1923. However, according to Yaşar Kemal himself, official records list his birth year as 1926—a bureaucratic delay in documenting a monumental life. He maintained that 1923 was the real year he was born, aligning his fate with the birth of the Turkish Republic. Whether 1922 or 1923, it makes no difference; he was cradled in the same cradle as the Republic. As if destiny had written that he would witness the birth of a new nation and bring light to its darkest corners.

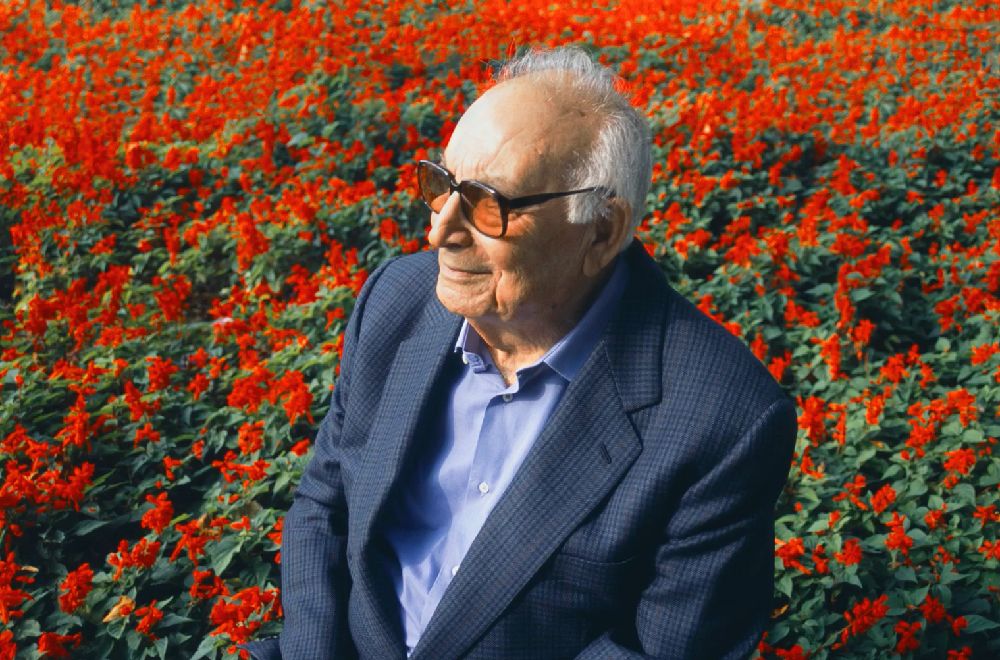

Photo: Prof. Dr. Kenan Mortan. From the archives of the Yaşar Kemal Foundation.

“My Father Died, and I Became a Stutterer”

At the age of five, he lost vision in one eye due to an accident. Soon after, he witnessed his father’s murder in a mosque.

“I was next to my father in the mosque when he was stabbed while praying. That night, I cried until morning, saying my heart was burning. After that, I became a stutterer and struggled to speak until I was twelve. But when I sang folk songs, I didn’t stutter. Not even once. The same happened when I read books. After the age of twelve, my stuttering disappeared.”

Growing up in the shadow of the vast divide between wealthy landowners and poor peasants, and under the grandeur of the Taurus Mountains, his childhood would later become the central stage of his novels. He started school at the age of nine, but his education lasted only two years, as he had to work to support his mother. From picking cotton to working as a mason, from driving a tractor to serving as a library clerk, he took on various jobs. However, the years he spent as a library clerk remained his most cherished. Among the bookshelves, he discovered Cervantes, Stendhal, and Tolstoy.

In his twenties, his rebellious spirit against injustice put him in trouble. He was arrested for allegedly trying to organize a tractor driver, and the words, dreams, and thoughts he had put on paper were thrown into the fire. “I asked for my manuscripts back, but they told me they had been burned in the stove at the Kadirli police station,” he recalled years later.

He acquired a typewriter and began earning a living by writing letters and petitions for illiterate villagers. In 1951, he stepped into the offices of Cumhuriyet newspaper, where his writings, particularly those about children struggling to survive on the streets, gained great attention and touched many hearts. Later, İnce Memed was published. This novel, which told the story of peasants suffering under the oppressive feudal system and a hero who rebelled against cruel landlords, resonated not only in Turkey but also worldwide. His journey from working in cotton fields to being nominated for the Nobel Prize was a truly remarkable one.

For Yaşar Kemal, literature was not just an art of storytelling but a voice of conscience. İnce Memed‘s escape into the mountains was not merely the adventure of an outlaw; it symbolized resistance against oppression, a rebellion against injustice, and humanity’s eternal struggle. The novel was translated into many languages. In a speech at Bilkent University in 2003, he described how he wrote İnce Memed:

“That winter was one of the coldest in Istanbul. I couldn’t afford firewood to keep warm. Wrapped in an old blanket, I typed on a machine with many missing letters.”

Through his novels, he depicted the struggles of people under the oppression of the feudal system, the strong ties between large landowners and the state, and the peasants’ fight for survival. He did not confine these critiques to his books alone but voiced them in his speeches and public statements as well.

During the turbulent 1960s, he stood firm against the harsh winds of politics. At one point, he had to live in exile in Sweden with his then-wife, Thilda, escaping political persecution. Neither the pain of being away from his homeland, nor the cold corridors of courtrooms, nor whispered threats could silence him. Identifying himself as “a Turkish writer of Kurdish origin,” Kemal was sentenced to 20 months in prison in 1996 for an article he wrote on the Kurdish issue in Turkey. However, international outcry led to the suspension of his sentence. Despite all challenges, he continued writing and speaking out with unwavering determination.

His message to his readers was clear:

“May those who read my books never become killers, but enemies of war. May they stand with the poor, for poverty is the shame of all humanity. May they cleanse themselves of all evil.” (Binbir Çiçekli Bahçe)

Although he is primarily known for his novels and stories, another significant aspect of Yaşar Kemal’s literary career was journalism. In his interviews and reports, he built a unique bridge between literature’s enchanting world and journalism’s realism. His journey in journalism, which began at Cumhuriyet newspaper in 1951, became a vivid, breathing panorama of Turkey’s modern history.

His book Röportaj Yazarlığında 60 Yıl (Sixty Years of Interview Writing) includes 12 powerful interviews covering various aspects of Anatolia—its diverse cultures, struggles, and hopes. From the streets of Diyarbakır to the dangerous world of smugglers, from the ruins of earthquake-stricken Hasankale to people surviving in caves, from Istanbul’s Sahaflar Market to the raging forest fires, and from the dreamlike landscapes of Cappadocia to the hidden stories of everyday life, his reports went beyond conventional journalism, bringing the depth and richness of literature into the field.

For Yaşar Kemal, journalism was not just about reporting facts—it was a creative process, just like his novels. “İnce Memed and my interviews are one and the same,” he once said, emphasizing the significance he attributed to the craft of reporting. When asked whether journalism was a branch of literature, his response was: “Not only is it a branch of literature, but journalism is undoubtedly literature.”

His journalism, novels, and stories transcended the borders of Turkey, reflecting the universal struggles, sufferings, hopes, and resistance of humanity. Though he is no longer with us, his words and the worlds he created continue to live on. Because Yaşar Kemal was not just a writer; he was a legend, a voice of an era, a storyteller of a geography, and a chronicler of human struggles.

And when he left, what remained was this:

“They mounted their beautiful horses and rode away, those good people, those magnificent souls… Those brave ones, those fearless hawks, those swift gazelles rode off on their steeds and took their leave. Never to return again. Never, never, never! Left to the rusting iron, to the corruption of man… It is hard to live in such a world. Where one evil enslaves a thousand good…”

“I Don’t Believe in Art That Is Detached from the People”

Yaşar Kemal’s stories continue to give voice to the forgotten, the unseen, and the oppressed. His words, thoughts, and the rich, colorful worlds he created are not just a part of Turkey’s literary heritage but a legacy for all humanity. Let his own words be the conclusion of this tribute:

“Whoever oppresses the people, whoever exploits them—whether it be feudal lords or the bourgeoisie—I stand against them with my art and my life. Just as flesh and bone cannot be separated, I want my art to remain inseparable from the people. In this era, I do not believe in art that is detached from the people.” (Yaşar Kemal Kendini Anlatıyor – Interviews with Alain Bosquet)

All of Yaşar Kemal’s books are published by Yapı Kredi Publishing.