The subject of The Phillips Collection‘s “Bonnard’s Worlds” exhibition, Pierre Bonnard, was one of the greatest painters of the 20th century. His style deeply influenced many painters, including Peter Doig, Mamma Andersson, Lois Dodd, Howard Hodgkin, Elisabeth Cummings, and Andrew Cranston.

As the heir of Impressionist and post-Impressionist movements, Bonnard was a member of the “Nabis” that emerged with Édouard Vuillard in the late 19th century, influenced by symbolism, Japanese art, and many other art forms. Although the Nabis disbanded in 1899, Bonnard continued to produce art, becoming inimitable with his unique style and expertise in colors.

After its opening at the Kimbell Art Museum, “Bonnard’s Worlds,” which later came to The Phillips Collection, showcases 60 paintings Bonnard created throughout his career. Organized by George Shackelford and Elsa Smithgall, the exhibition takes a retrospective approach to Bonnard’s created spaces and worlds, rather than presenting them chronologically. As visitors progress through the exhibition, they find themselves immersed in a spiral of intimate emotions.

Japanese prints had a significant influence on Bonnard. The Japanese theme “Oku” is concerned with how spaces (real or imaginary) are layered and organized as one moves from public areas to more private ones.

In Oku, the important thing is not just the movement towards a clear goal, but towards something unknown and possibly unattainable. Unlike Western design, which is based on moving towards a specific goal, it also involves moving towards an unknown or unattainable goal, which can sometimes lead to disappointment.

Bonnard’s art is similar to this theme. In addition to the sensory pleasures his paintings evoke, he reinforces the viewer’s desire to reach the type of intimacy they are seeking (whether spiritual or worldly) by placing subtle barriers between them and the viewer.

The “Bonnard’s Worlds” exhibition aims to animate this dynamic by moving visitors from the outside to the inside with its design. The exhibition opens with paintings of Paris and rural landscapes from the artist’s perspective, progressing through garden and terrace depictions. In the next section, compositions fold distant outdoor scenes into close indoor spaces through large windows. Subsequently, after indoor depictions, the exhibition moves on to the more private, erotic parts of the bedroom and bathroom. Finally, visitors see the mirrors; Bonnard’s self-portraits.

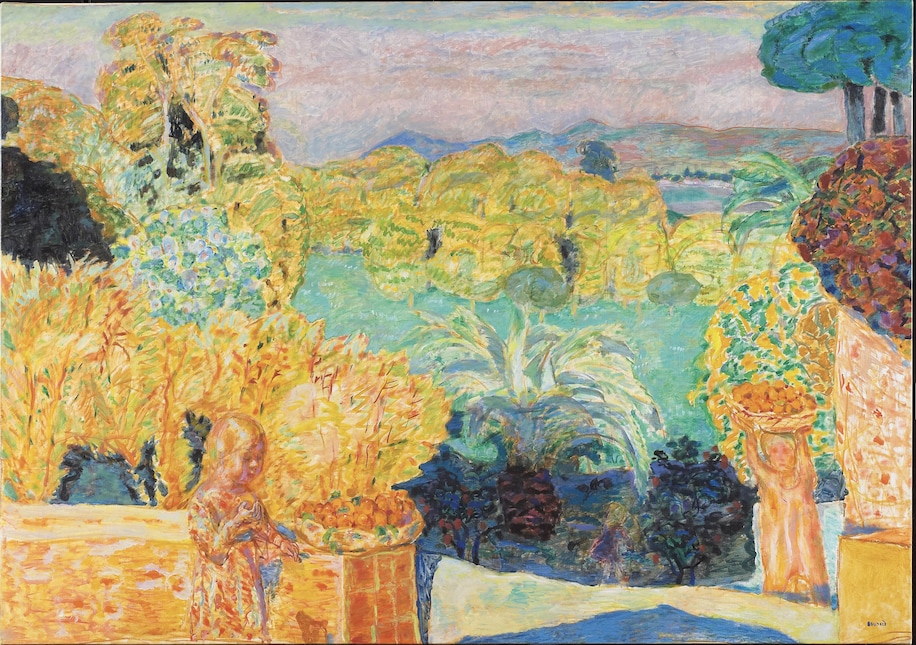

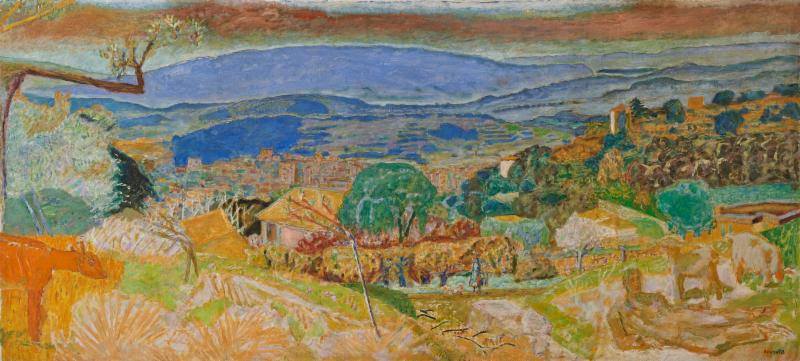

Personal experience was at the core of Bonnard’s works, with space being at the center of this experience. However, Bonnard never directly painted what he saw. He transformed sight, memory, and emotion into colorful paint arrangements. He worked in various places, including Paris and Vernonnet (just a few kilometers from Claude Monet’s garden in Giverny). In the 1920s, he discovered the French Riviera and eventually bought a property named Le Bosquet (The Grove) in Le Cannet, overlooking Cannes.

The exhibition begins with Bonnard’s depictions of expansive landscapes and towns. Some of these paintings evoke the vast landscapes of Pieter Bruegel. However, despite being large paintings, Bonnard’s touch creates a sense of close connection to every part of the landscape.

Bonnard loved to take walks with one of his dachshunds every morning. As he aged, he increasingly desired a more direct life in nature. His landscape paintings, teeming with abundance, express this desire. Masterpieces such as “Landscape at Le Cannet” and “Earthly Paradise” convey this desire with high horizon lines and sky depictions.

According to art historian Nicholas Watkins, Bonnard initially conceived his outdoor paintings as a “light-filled wall hanging that dissolves over time and space.” Later landscapes became airier, more intuitive, and less planned.

In the later sections of the exhibition, showcasing outdoor terraces and views from windows, some of Bonnard’s greatest works are displayed. Among these are “The Terrasse Family,” a large and bustling composition, “The Terrace at Vernonnet” set in Vernonnet, and “The Palm” from Le Cannet. The last two paintings are part of The Phillips Collection. The museum’s founder, Duncan Phillips, purchased the first two Bonnard paintings in 1925 and continued to build his collection of Bonnard works in the following years.

“Young Women in the Garden,” which appears to be painted on the terrace of Bonnard’s residence in Vernonnet, depicts the face of Bonnard’s blonde mistress, Renée Monchaty. In the lower right corner of the painting, there is a cropped image of Marthe. Bonnard tells a story with the small hints he places within the paintings.

Monchaty, who was about 30 years younger than Bonnard, entered his life in 1920. The following year, they spent two weeks together in Rome, and Marthe, whom he had met almost 30 years earlier, learned of this event. After some confrontations, Bonnard married Marthe in a hasty ceremony in 1925. Two weeks later, Monchaty was found dead, having committed suicide.

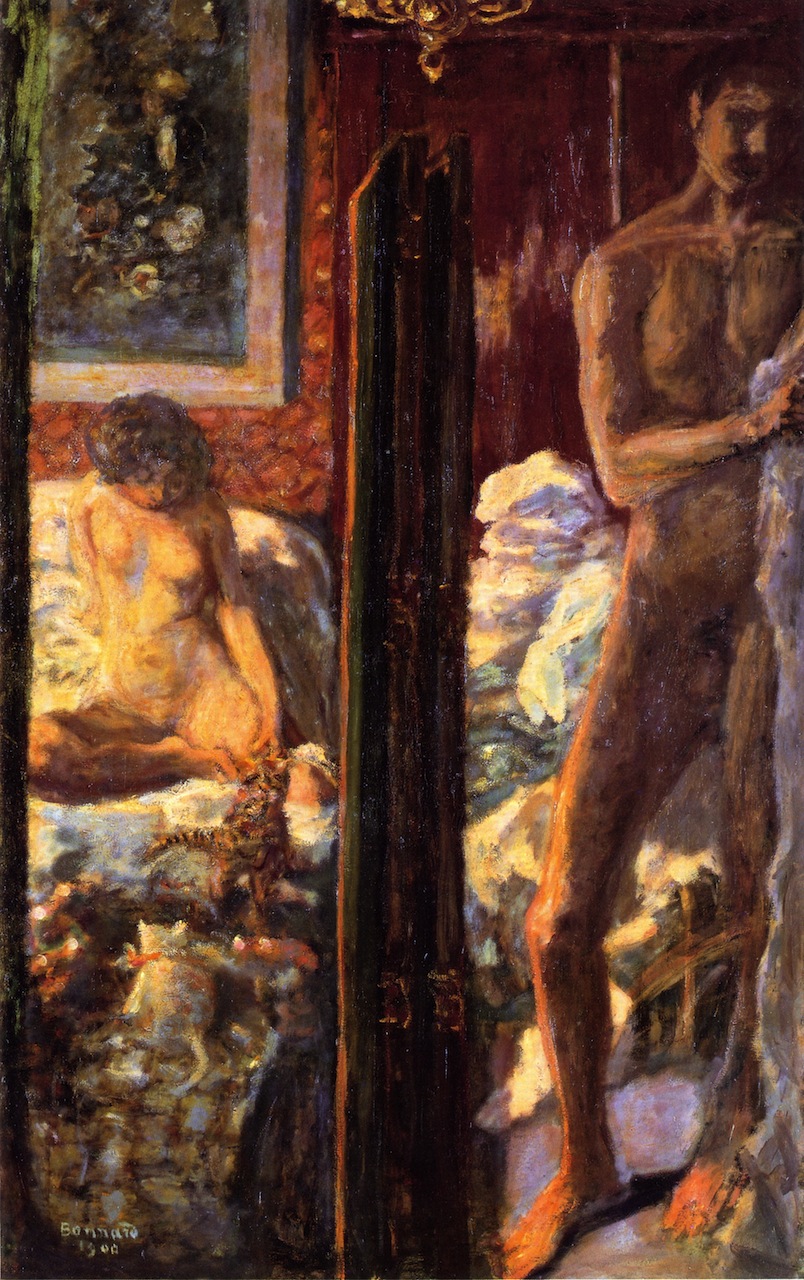

As Shackelford writes, Bonnard constantly leaves clues to solve puzzles in his paintings. For example, an inconspicuous knob may be the only clue that a thin vertical stripe on the edge of a painting could be a door.

The trembling lines, coarse bodies, and speckled colors in Bonnard’s paintings, which he said sacrificed form for colors, reach intensity in the last part of the collection. These paintings include depictions of bedrooms, Marthe in the tiled bathroom at Le Bosquet, his own face and body seen in the mirror.

A painting with the psychological intensity of Edvard Munch‘s works, “Man and Woman,” dramatically divides a couple after sexual intercourse with a curtain. The woman sits naked in bed in a room illuminated by light, looking at where her leg meets her thigh. The man is preparing to dress on the shadowy side. While the painting leaves the viewer curious about what happened between them; the clues help to create a story in your mind.

Bonnard creates a contrast between his self-portraits and the series of paintings where he depicts Marthe in the bathroom during the same period. Contrary to the sense of impending death he achieves in his self-portraits, the portrayal of Marthe, shielded and distant from the hardships of old age, draws attention to the striking difference in emotion and themes in Bonnard’s different works.

Bathroom paintings are among the defining works of Bonnard’s career. However, another feature of the paintings is that they do not fully reflect reality. Despite Marthe being in her 50s, 60s, and then 70s, Bonnard continued to depict her with the body of a young girl. But this was not surprising for Bonnard because everything he painted had a quality of being recreated from imagination in the style of Marcel Proust or reclaimed from time itself.